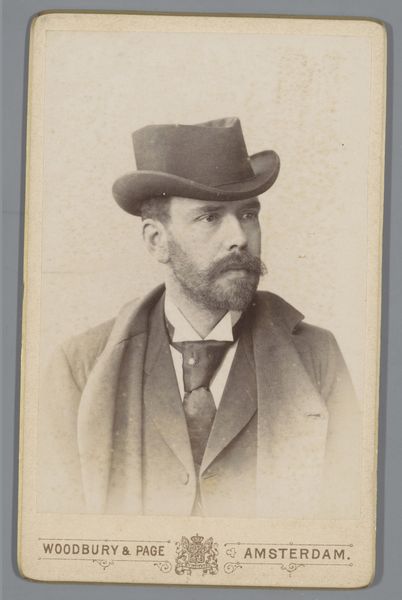

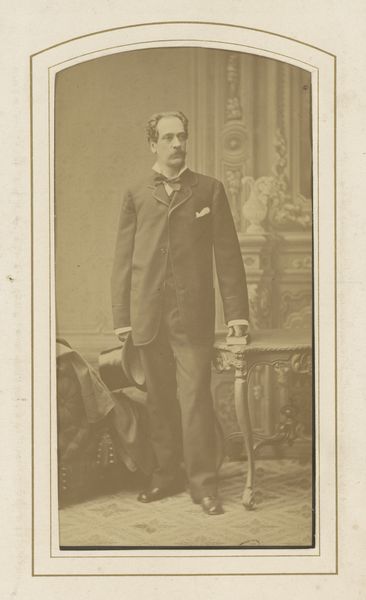

Dimensions: height 134 mm, width 96 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

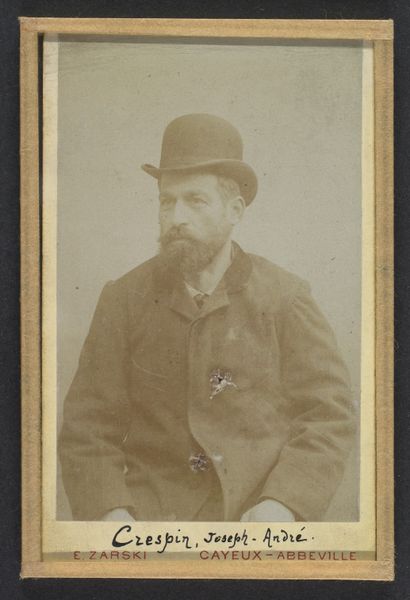

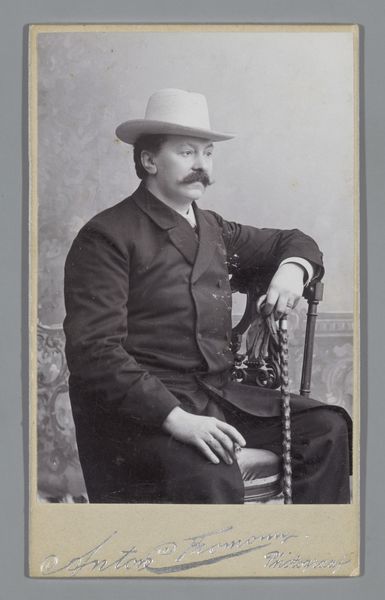

Curator: The image before us is entitled "Portret van een man met hoed", or "Portrait of a Man with a Hat", made sometime between 1860 and 1900 by Charles Chambone. It's a gelatin silver print, a fairly common process for photography during this time. What's your initial reaction to it? Editor: He seems like he would be particular about his tea. There is something about the tones here; it gives an air of gentility, like he is about to give advice. And notice how muted and simple this early photographic paper appears to be; very different from how we mass-produce things today. Curator: The gentleman's attire speaks to the social expectations placed upon men of his era. His posed nature emphasizes a desired level of class consciousness that dictated presentation. How do you see those historical labor dynamics coming to the surface in the piece itself? Editor: The man's clothing speaks volumes; that quality suit was a marker of affluence tied to industrial textile production and the labor of many. The materials present -- cloth, gelatin, silver – represent entire chains of production and consumption, spanning across different social classes and geographical boundaries. We might be looking at consumption disguised as mere elegance. Curator: Absolutely. It also hints at colonial exploitation. These raw materials were not often locally sourced. But in many ways this form of romanticized portraiture has affected the very narrative of this period. To be considered an accomplished man of a higher caliber demanded wealth which has further reaching ethical implications when you view images from this time. Editor: I agree, the seemingly straightforward portrait quickly spirals outward. The silver gelatin print shows the transition of photographic printmaking to being accessible on a larger scale than even early processes like daguerrotypes allowed. Mass reproducibility impacted not just access to media, but changed what value society placed on photographic material. Curator: Looking closely, you start to unravel narratives about identity and representation in the 19th century, reflecting hierarchies and structures, don’t you think? We have so little recorded history of women and poor populations in the same format which means they were either excluded or forced into a different bracket. Editor: Indeed, by looking at how these portraits were constructed—through photographic means and material conditions—we gain insights into class structures and commodity exchange of that period. An image like this provides more than face value upon scrutiny, revealing production’s complex socioeconomic elements, including distribution and means.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.