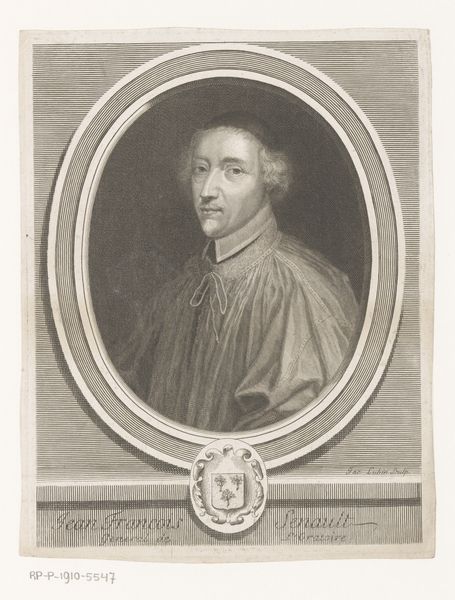

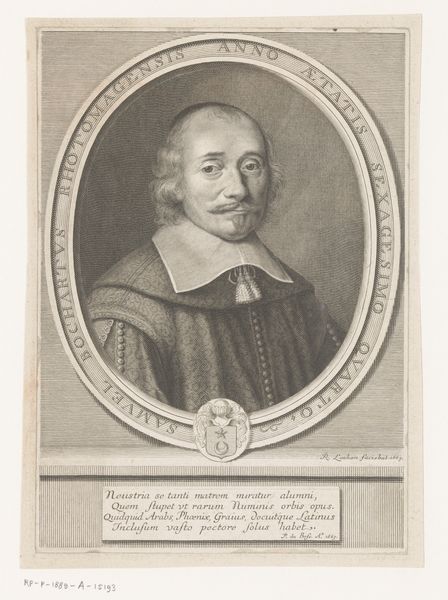

engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

#

historical photography

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 332 mm, width 257 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have a piece titled "Portret van Eustache Le Clerc de Lesseville." Dating back to 1661, it’s an engraving by René Lochon currently housed in the Rijksmuseum collection. Editor: Immediately, I notice the intricate details achieved through the engraving process. There's an incredible softness despite the rigid medium, lending an almost ethereal quality to the subject’s expression. Curator: Precisely. This softness was key in baroque portraiture, softening any hard lines of the social elite. Lochon wasn't just representing an individual; he was also crafting an image that supported Le Clerc's role and authority as Bishop. Note the oval frame containing Latin inscriptions affirming his position. Editor: That inscription situates him, definitely, but what does it tell us about the context of power at the time? How did images of authority shape society, and in what ways could ordinary people relate to them? It’s interesting that religious icons were reproduced as prints to be distributed at a time when not many had access to art or knowledge. Curator: Yes, the dissemination of such prints was crucial in projecting power, reinforcing social hierarchies. The very act of commissioning such a portrait was itself a performance of status and self-awareness. Editor: It really frames questions about who had access to image-making, reproduction, and therefore, a sort of visual immortality. Where do such portraits exist now, what’s on the walls of everyday homes? Who are they memorializing? It creates an opportunity for broader conversation about visual legacy and its impact on contemporary self-perception. Curator: Thinking about that legacy, this image serves as a visual anchor to that specific historical and religious moment, preserved and presented to us by the institution of the museum. Editor: Indeed, thinking critically about these echoes helps to examine our world, both the way it’s been recorded, and what’s left unseen in visual culture.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.