Perseus and Medusa, from 'Game of Mythology' (Jeu de la Mythologie) 1644

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, engraving

#

drawing

#

ink drawing

#

baroque

# print

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

horse

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: Sheet: 1 3/4 x 2 1/8 in. (4.5 x 5.4 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

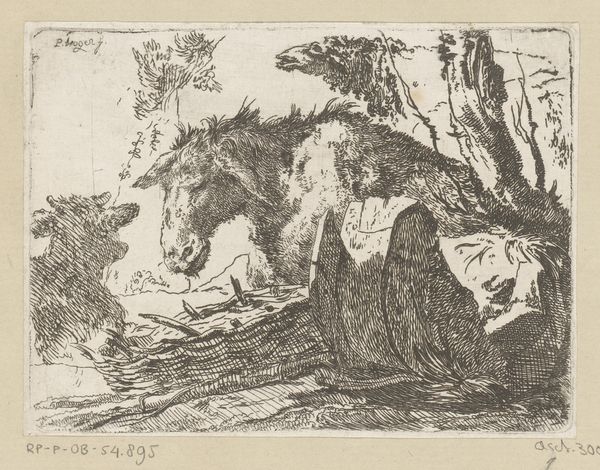

Curator: Welcome. Here we have Stefano della Bella’s “Perseus and Medusa, from 'Game of Mythology' (Jeu de la Mythologie),” an engraving dating back to 1644, now residing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: It’s incredibly detailed! There's such a dramatic weight to the scene. I can't help but notice the intense expression on Medusa’s severed head – it practically leaps off the page. Curator: Della Bella was a master of printmaking, his lines capturing an impressive sense of depth and movement. Notice how the hatching defines form and creates tonal variations despite the inherent limitations of the medium. I am struck by how meticulously the entire engraving was completed and replicated in order to be consumed en masse. Editor: Absolutely. And beyond the technical skill, the piece immediately evokes considerations about power, gender, and the gaze. Medusa, traditionally seen as a monster, is here frozen in a moment of agonizing defeat. Is della Bella using mythology to comment on violence and control over the female body, and male strength versus women's 'monsterous' characterizations? Curator: It’s fascinating how the very act of Perseus gazing indirectly via his shield— a conscious avoidance of Medusa's petrifying gaze— is central to the method, material components, and completion of his endeavor. The reflected gaze then is itself a tool, utilized as equipment to achieve this very goal. The shield itself—what's its craftsmanship? Editor: The horse next to Perseus might also indicate a specific classical education afforded to viewers from the 17th Century who might understand the allusion, specifically the scene when Medusa was raped by Poseidon in a temple dedicated to Athena; Pegasus and Khrysaor sprang from her neck when she was decapitated by Perseus. This version leaves a lot unsaid while invoking all those other stories as subtext. Curator: Precisely. And by understanding the methods and components with which such historical narratives are both crafted and delivered to a broader audience in society at large we start to unpack more significant implications of the very creation process. It forces the consideration of the entire social and production context under which artworks operate as meaningful vehicles of thought and culture. Editor: It seems we are both agreeing that, in studying Bella's engravings like "Perseus and Medusa" we gain a deeper understanding of cultural narratives of gender, sexuality, and power structures, both then and now. Curator: Definitely, thinking about how art-making intersects with culture in these eras continues to change the questions we bring to it.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.