engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

#

portrait drawing

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 447 mm, width 344 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

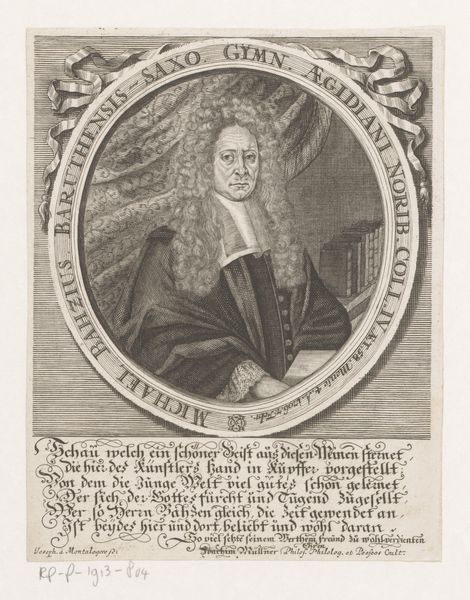

Curator: Let’s consider this engraving, a 1716 portrait of Johann Philipp Treuner by Johann Andreas Pfeffel. Editor: Yes, the detail is quite impressive. Looking at it, I am struck by how formal and posed it is, reflecting maybe the sitter’s importance, or social status. What specifically draws your attention to it? Curator: Immediately, my focus is on the engraving itself. Consider the labor invested in creating this image, the precise cuts of the burin on the copperplate. The lines are not just descriptive; they're the result of a specific technique and a tangible material. What social role did printed portraiture play at that time, who had access to this, and what was its cost? Editor: That’s a very interesting point, the level of labor and the type of material… Curator: Consider the social context. The very act of producing multiple copies of this man's likeness through an engraving suggests a growing accessibility to art and portraiture. Also, think about what type of audience was consuming portrait engravings like these, not only what was available to see, but who owned this images? This raises the broader issue of who controlled the means of visual production at this time, right? Editor: Absolutely! This wasn't just about aesthetics, it was about disseminating power. And what can you say about the book placed at the left, near the oval? Curator: Good question! Books during that period held considerable power, not just in spreading religious ideologies but also as tools of cultural dominance. This brings back the questions surrounding production and who controlled access to information and visual representations. Editor: I see! By understanding how these portraits were created and distributed, we learn much more than just the sitter’s identity. We also learn a lot about the social structure in general at the time.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.