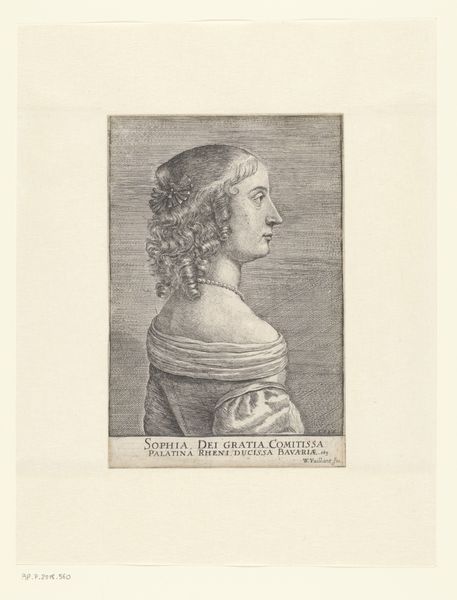

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

classical-realism

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 245 mm, width 145 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have "Herme met bustes van Mercurius en Minerva", an engraving by Cornelis Galle I, dating from 1610 to 1650. It currently resides here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: Oh, it’s stark! And the profiles – so cool, so detached. Like a monument you'd find overgrown in some forgotten garden. There's something...oppressive about that double-headed aspect. Curator: The double herm—or "Herme" as its titled in Dutch—certainly plays on duality. You have Mercury, quick-witted messenger, juxtaposed with Minerva, the strategic goddess of wisdom. Look at their helmets. Editor: Yes! One winged, the other crested with… is that a raptor of some kind? An owl perhaps, for wisdom, perched right there? What a heavy headpiece to bear. The composition almost feels... combative? Each profile facing outwards, defensive. Curator: I find it interesting to examine it beyond the gods and focus on what Hermes represented over time; a boundary marker, a liminal guardian. Galle's image almost echoes the two-faced god Janus of Roman mythology, a figure of transitions, passages, and duality. Editor: So, it's not just a portrait, but a marker, a signpost... intriguing! It really captures this sense of opposing forces held in uneasy balance. Makes you think about the decisions we all face and how difficult it can be to choose a path. Curator: Consider how that plays out politically. Images of such gods often functioned as statements of cultural aspiration in the 17th Century, recalling specific values linked with Imperial Rome. These busts project ideals back onto their owners. Editor: It does carry this weight of...cultural baggage, doesn’t it? Those helmets! What better symbol for conflicting ideals and hidden identities? Even rendered in simple engraving the level of detail really hints at the political machinations hidden in everyday life. It really makes me think! Curator: Indeed. It provides us a snapshot into the early modern period through which images functioned not merely as art objects, but active cultural and political agents. Editor: Well, I see it now as so much more than a stuffy old engraving. There’s a hidden emotional landscape—one of tension and strategic choices etched right onto its surface. Curator: That’s what I admire most. Centuries melt away and symbols start breathing again.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.