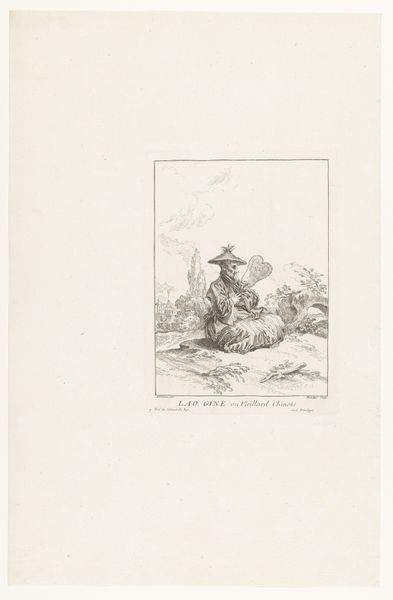

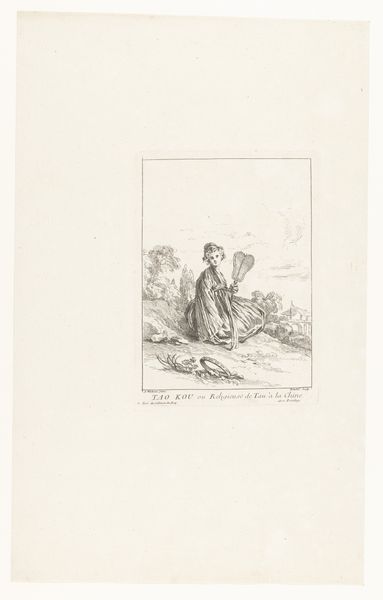

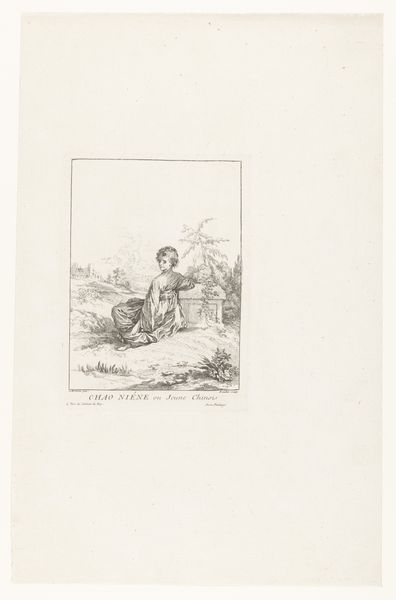

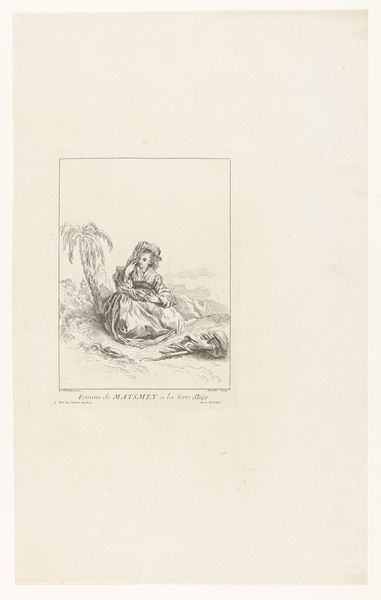

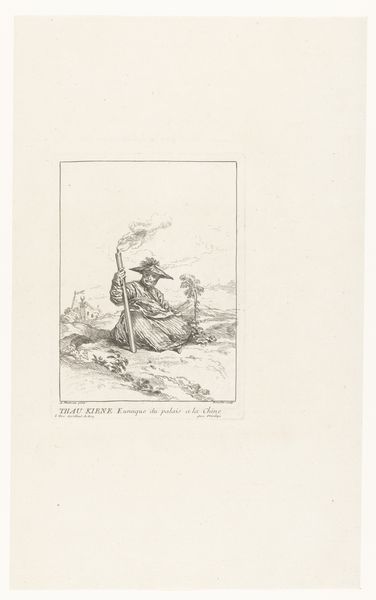

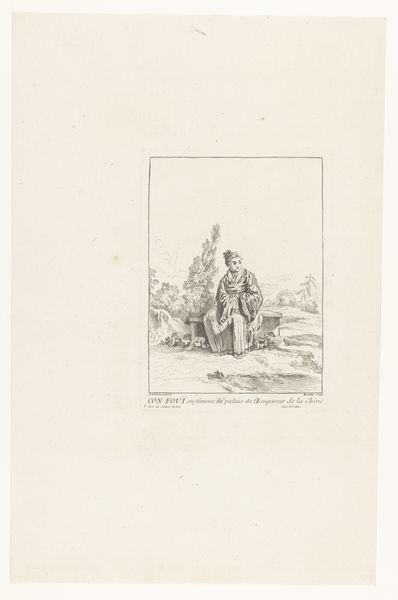

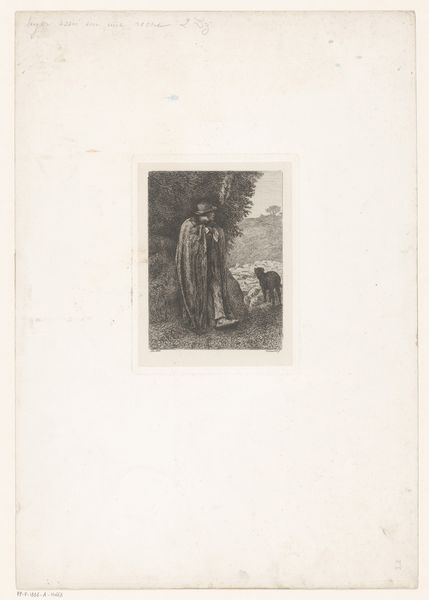

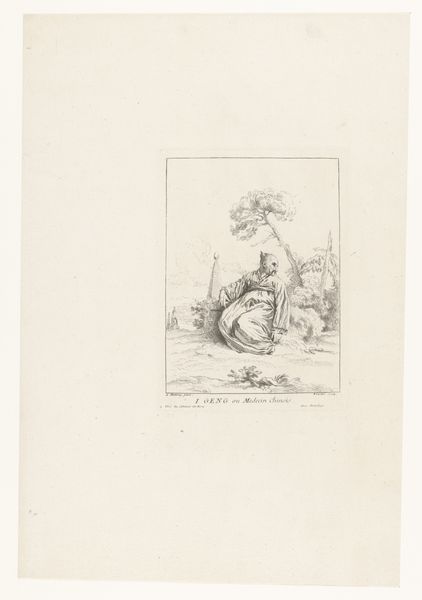

drawing, print, etching

#

portrait

#

drawing

# print

#

etching

#

pencil sketch

#

landscape

#

orientalism

#

genre-painting

#

rococo

Dimensions: height 213 mm, width 155 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This etching by François Boucher, made around 1731, is called "Chinese geestelijke, zittend in een landschap," which translates to "Chinese cleric, sitting in a landscape." I find its monochrome rendering very evocative. Editor: There's a delicacy to the line work. Yet, something about this scene feels...unsettling. It speaks to the power dynamics inherent in the European gaze upon other cultures. Curator: Yes, this print provides insight into the popular 18th-century fascination with what Europeans imagined the 'Orient' to be. Note Boucher's handling of the etching process; the varying line weights creating subtle tonal shifts on the page. How does this process inform the work's reading, for you? Editor: The rococo period favored lightness, playfulness—but through an activist lens, this lightness can seem like a superficial engagement. The woman in the scene, is that supposed to be Nikou a Chinese "korenze" a religious, or a common woman? Curator: What makes the piece significant is how Boucher's artistic labor, his production, becomes a reflection of European attitudes towards Asia. There is, clearly, an investment by the public to consume the orientalist. The material and methods are of great value, the final product an exercise in European perspective and construction. Editor: Precisely. It becomes a question of who benefits from the representation, and how it shapes understanding—or misunderstanding. Even in the deliberate artistry, it may be enforcing stereotypes, or exoticising Nikou and her culture, reducing a whole world to decorative motifs for European consumption. Curator: Considering Boucher’s Rococo sensibilities and how printmaking disseminates ideas through material production, can we find areas in which Eastern techniques informed European print making? How could Eastern material making practices, so skilled in pottery and silks, teach the 'West'? Editor: The print serves as a document, an artifact. It is a snapshot into complex power dynamics, and speaks volumes about European society's need to create fantasies about the 'Other'. Understanding this helps unpack persistent legacies of colonialism that affect representation and cultural exchange still. Curator: Agreed. This work presents the means of reproducing desire, while maintaining the mystery of the other; and Boucher’s labor underscores that problematic vision of a constructed "Orient" which holds great implications. Editor: It forces us to critically engage with not only what is shown, but also what is left unsaid—the stories and perspectives that remain outside the frame.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.