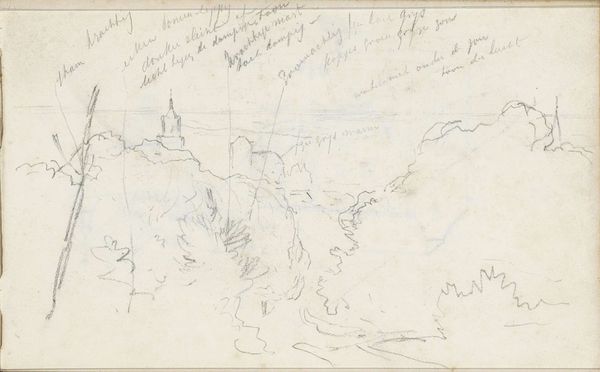

drawing, pencil

#

drawing

#

impressionism

#

landscape

#

folk-art

#

pencil

#

genre-painting

#

realism

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

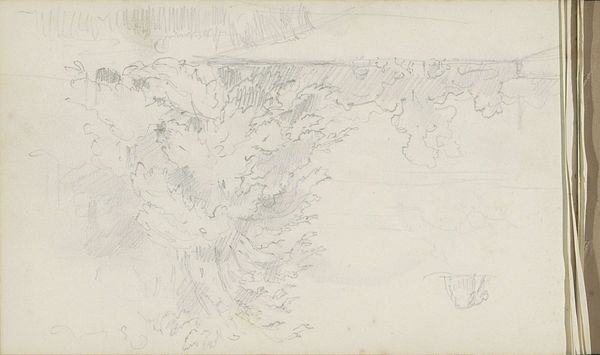

Editor: So, here we have Anton Mauve’s “Herder met een kudde schapen,” a pencil drawing from around 1876-1879. It feels almost unfinished, just wisps of lines suggesting figures and a landscape. What's your perspective on it? Curator: What strikes me immediately is the relationship between labor and the landscape being depicted. Consider the raw materials: pencil and paper. They are cheap, accessible, industrial products of their time. Now think about what’s being represented: a shepherd and his flock. The drawing is less about the romantic ideal of rural life and more about documenting the very physical work of shepherding within an emerging industrial economy. Don’t you think? Editor: I suppose, but it feels more atmospheric than documentary. Is Mauve making a statement about the working class, or just recording what he sees? Curator: It’s not about direct protest, perhaps. But look at the hurried nature of the lines, the lack of polish. It emphasizes the ephemeral, perhaps even the precarious, existence tied to the land. These quickly rendered sketches point toward the social realities underpinning rural life, especially the economic drivers related to wool and land use that dictate these laborers' lives. Also, the choice to use such a humble medium removes it from the preciousness of 'high art', making the subject accessible. Editor: So, you’re saying the materials and technique are intrinsically linked to Mauve's depiction of labor? Curator: Precisely! The very means of production, pencil on paper, mirrors and subtly comments on the production of wool and meat that defines the shepherd's world. Editor: I never thought about it that way before. It’s not just a pretty picture; it's about the system! Curator: Exactly. Seeing art through the lens of materiality opens up new avenues for understanding its social and economic contexts.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.