Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

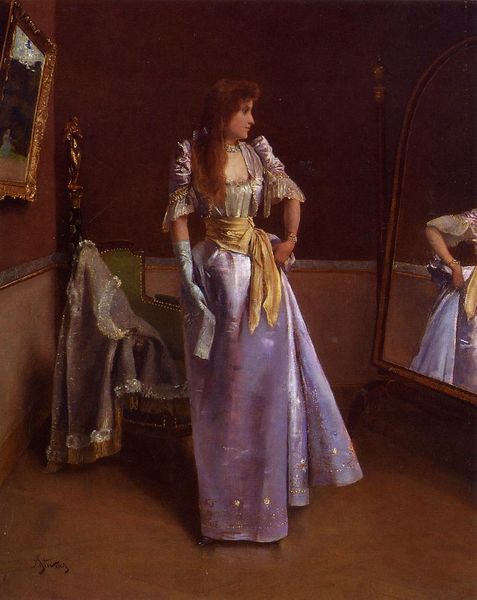

Curator: Let's spend a few minutes with John Singer Sargent’s "Madame Paul Escudier," painted in 1882. The somber color palette immediately strikes me. Editor: Yes, it's a portrait swathed in these deep blues and browns—almost oppressive, even with the burst of light from the window behind her. There's a formality but also a subdued emotion that I find fascinating. Who was Madame Escudier? What's her story? Curator: Beyond the story we might construct around her, consider Sargent’s labor: the weave of the canvas, the blend of pigments. Oil paint lends itself beautifully to capturing the texture of that satin gown, its folds shaped not just by gravity but also by whalebone and social expectation. This materiality speaks volumes. Editor: Agreed, and think about how Sargent's choices serve to position his subject. The setting—a wealthy woman’s parlor, a manufactured and meticulously constructed reality. This portrait is as much about class as it is about the individual. The artist deliberately invites these readings. Curator: And he's so good at creating this interplay of textures – the rug, the dress, the velvety chair that’s mostly cut out of the frame, creating depth and interest. He's highlighting the luxurious environment in a manner aligned with consumer culture—the commodification of artistry, really. Editor: Precisely. We need to consider the societal expectations and constraints placed on women of Madame Escudier's social standing, the male gaze at play. How does that intersect with Sargent's own identity as a portraitist catering to a specific social strata? Curator: Well, we know Sargent moved easily among the elite; his success depended on commissions from figures like Madame Escudier. He captured their likeness, their taste in fashion, in furnishings… He documents a particular moment in the history of material culture. Editor: These commissions, and the art that emerged from them, solidified societal hierarchies and dictated definitions of beauty and prestige. To understand this portrait fully, we must examine the power structures in place at the time, the inequalities that underpinned its creation. Curator: That close analysis is essential. When I look at "Madame Paul Escudier" I’m reminded how artists' hands are always involved in more than artistic expression, deeply entwined in social dynamics. Editor: Absolutely. Thinking about Sargent, about Madame Escudier, challenges me to critically assess art's role in perpetuating social and economic narratives, even today. Thank you for offering your insight on this compelling portrait.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.