drawing, print, ink, engraving

#

drawing

#

allegory

# print

#

figuration

#

ink

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: 5 3/16 x 4 7/8 in. (13.2 x 12.4 cm) (fan shaped)

Copyright: Public Domain

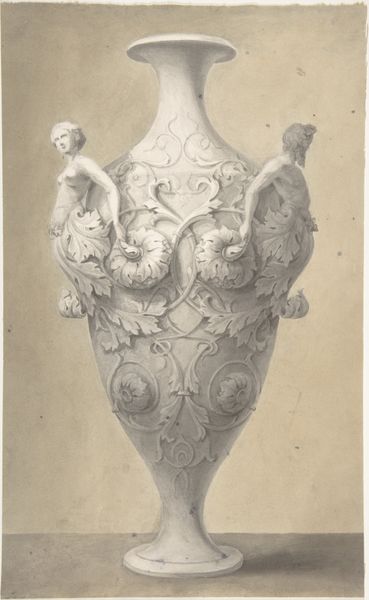

Curator: Look at this fascinating, albeit damaged, piece here at the Met. It’s called “Design for a Cup(?)”, and the museum dates it to somewhere between 1800 and 1900. It’s a drawing done in ink, and appears to be an engraving or intended as one. Editor: My initial reaction? The heavy ink work, the contrast between light and shadow, and the somewhat obscure imagery create a rather somber, perhaps even ominous, atmosphere. Curator: Well, the piece is full of allegory. Two primary scenes are presented; to the left, we see what appears to be a crowned woman at a table, maybe a queen or goddess, sharing a drink with a child; the scene on the right features a solitary, similarly unclothed figure under what I'm interpreting as rain clouds. Editor: It's difficult to ignore the patriarchal structures implied in that binary, almost suggesting different fates or experiences based on gender. Who decides who is offered food and drink? And the water almost seems toxic, threatening, especially considering what historical environmental policies tend to subject poorer communities to. Curator: Absolutely. We must consider how such imagery circulates within systems of power and meaning-making, informing societal norms. But the figures here might reflect ideals or myths, depending on its origin. Unfortunately, it's listed as Anonymous. Considering the time period and subject matter, do you suppose its original context held particular political or social significance for its intended audience? Editor: Without question. The imagery could represent everything from anxieties about governance to gendered expectations. And, while anonymous, it inevitably carries the echoes of a dominant, most likely male, gaze from that period. Curator: Right, but seeing it exhibited now changes things too. Displaying it alters the reception and allows a critical questioning that can dismantle some of those outdated power dynamics. Editor: True, it forces us to ask: who created this? For whom? And what narratives did it reinforce? It speaks volumes about art institutions then and even now. Curator: Indeed. It's not just about appreciating the artwork's supposed inherent value, but interrogating how it reflects broader cultural values, even unintentionally. Editor: Precisely. It’s about challenging historical canons, reclaiming marginalized narratives, and empowering a more nuanced interpretation of art.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.