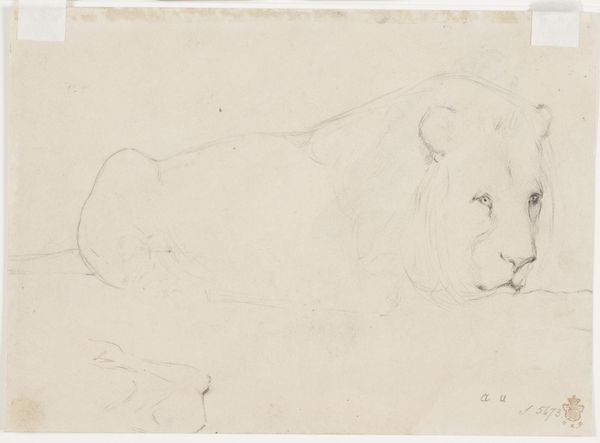

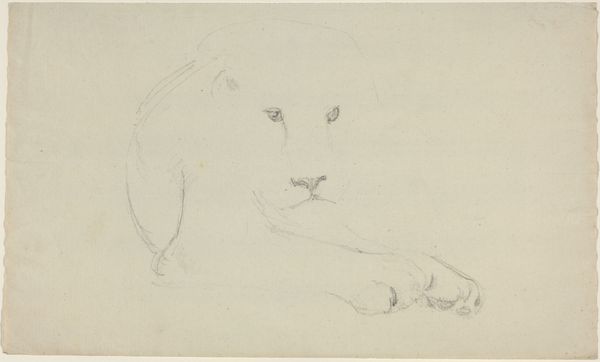

drawing, dry-media, pencil

#

drawing

#

animal

#

pencil sketch

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

dry-media

#

pencil

#

academic-art

#

realism

Dimensions: height 333 mm, width 215 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

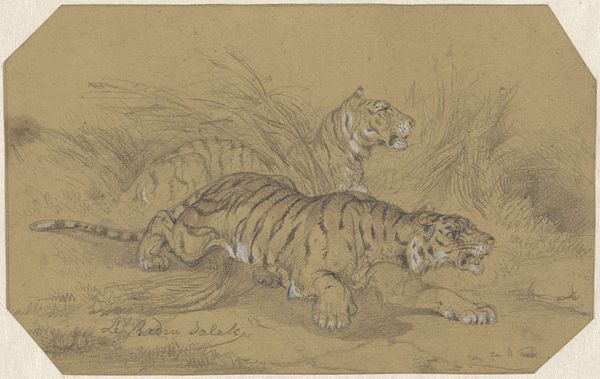

Curator: Here we have “Three Studies of a Tiger,” a pencil drawing by Guillaume Anne van der Brugghen, created sometime between 1821 and 1891. Editor: The immediate impression is one of repose. These tigers, captured in graphite, exude a surprising tranquility. There's a gentleness here that contradicts the creature’s inherent power. Curator: Indeed. The composition is quite interesting. Observe how van der Brugghen employs the dry-media pencil to delineate three distinct poses of the resting tiger, one atop the other. Note, particularly, the delicate cross-hatching that models form and creates a sense of depth. Editor: I'm struck by the physicality of the drawing itself, the intimate marks left by the artist’s hand. You can almost feel the pressure of the pencil on the page, revealing a fascinating tension between the smooth texture of the paper and the potential energy of the tiger’s form. One wonders about the access Van Der Brugghen might have had to study the Tigers closely? I wonder how closely he might have considered questions of conservation and our ethical relationships to wild animals through the image making? Curator: Perhaps his studies were academic. There's a clear engagement with the tenets of Realism; the meticulous observation and anatomical accuracy suggest a deep understanding of the animal's form. Notice the precision with which he renders the stripes and the subtle variations in texture across the fur. Editor: Considering that a drawing is produced over a duration, it makes you consider not only his level of involvement with the animal form itself, but how social pressures informed both the handling of the medium and choice of subject matter, which, in turn, may reveal much about that era's complicated relationship to notions of domesticity, control, and even imperialism. Curator: I find this emphasis on the interplay between academic technique and close observation most compelling. The three studies each capture a nuanced expression—a slight shift in weight, a subtle adjustment in the position of the head—that offers a complete, almost cinematic portrait of the animal in a private, unguarded state. Editor: And I’m struck by how it speaks to the means of image making, social pressures and animal subjectivity and, perhaps, reveals to us the historical and embodied knowledge and value systems inherent in art and design of that era.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.