Dimensions: height 165 mm, width 106 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

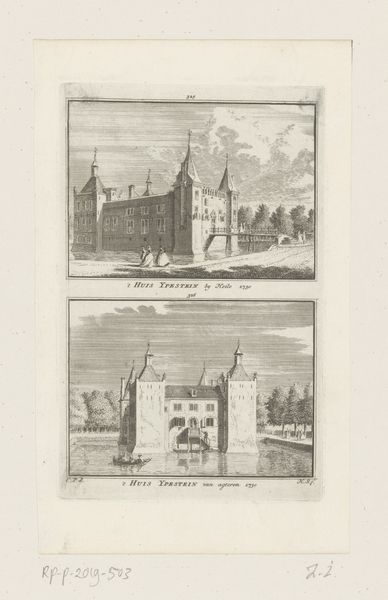

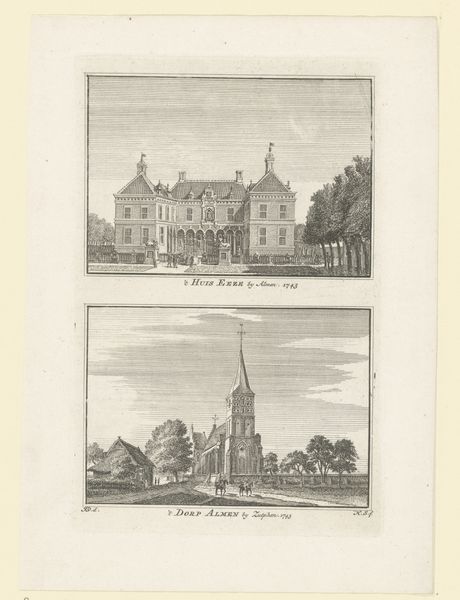

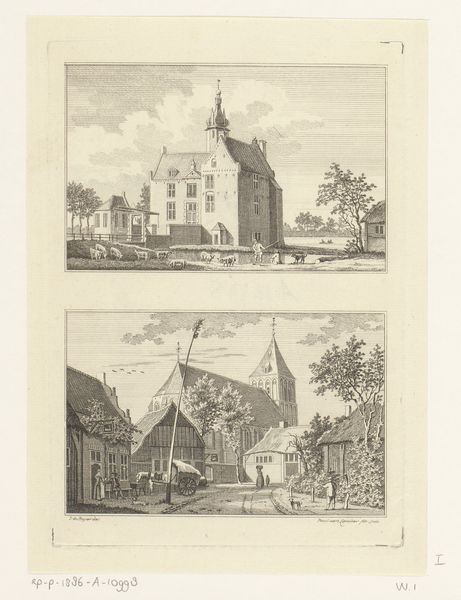

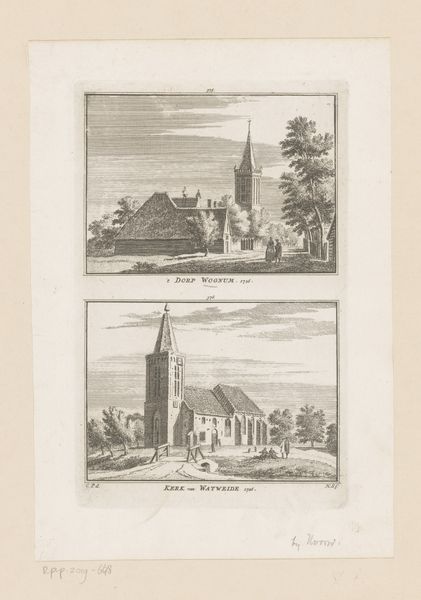

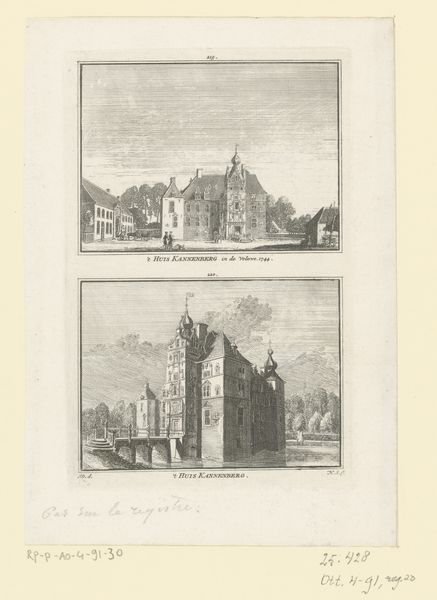

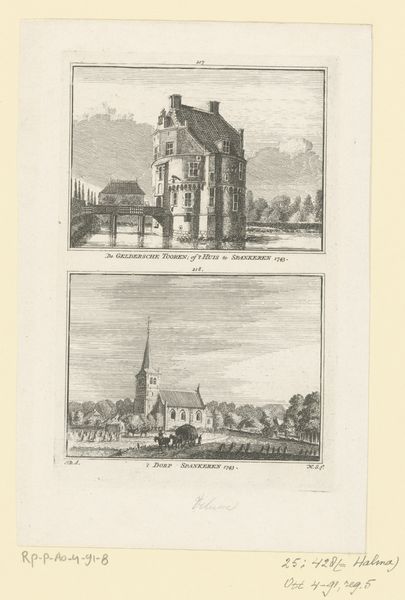

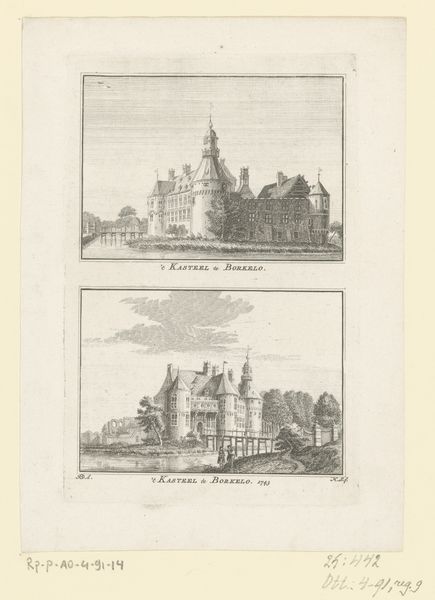

Curator: This print, dating from between 1745 and 1792, by Hendrik Spilman, presents us with two distinct views: ‘Gezicht op Netterden’ and ‘Gezicht op Huis Woldenburg,’ both rendered in meticulous engraving. It's currently held at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: My immediate feeling is quiet contemplation. These scenes have a hushed stillness. It's like eavesdropping on a memory, almost faded. The architecture of Huis Woldenburg in particular has a fantastic almost dreamy air about it. Curator: Spilman’s work fits into a tradition of topographical prints, a common genre during the Dutch Golden Age and beyond. Prints like this served as visual records and even promotional material for these locations. It provided a certain perspective that was used for documenting the landscape in those years. Editor: Promotional, eh? Perhaps it lured a lord or two with dreams of tranquility. I imagine living in Huis Woldenburg could be a life of utter comfort and reflection—though all that water nearby... a little damp perhaps? But the print style almost invites the viewer into these little worlds, each captured so delicately. Curator: The contrast between the village scene of Netterden, focusing on its church, and the stately home of Woldenburg is quite interesting. It's representative of the social structure of the time, juxtaposing communal life with individual wealth and power. Notice how Spilman meticulously depicts the architectural details of both, demonstrating an interest in capturing both the sacred and secular aspects of Dutch society. Editor: Yes, indeed. Almost like showing how God and Mammon are happily residing in the same corner of the world. All that careful detail… but that perspective of it… how those branches curl over that gorgeous building. Very nice. You know, one is left to wonder what has happened to both these wonderful buildings throughout time. How do you see that reflected in the print itself? Curator: I feel it captures a sense of preservation and legacy that landowners wanted to convey, that would communicate their position in society at the time and into the future. These weren't just images but claims about history and place. It provided them a stake in Dutch history itself. It represents them having ownership over the future itself through preserving these visual renderings of places. Editor: Hmm. I hadn't thought about legacy in that light. To think that those folks used it as calling card throughout time in that respect. Maybe those images would work well even in our own era. It certainly is an impactful visualization!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.