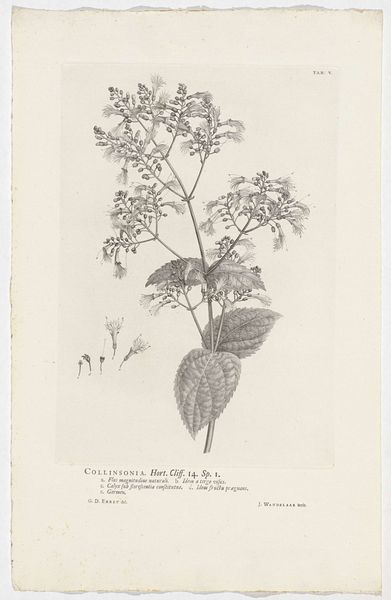

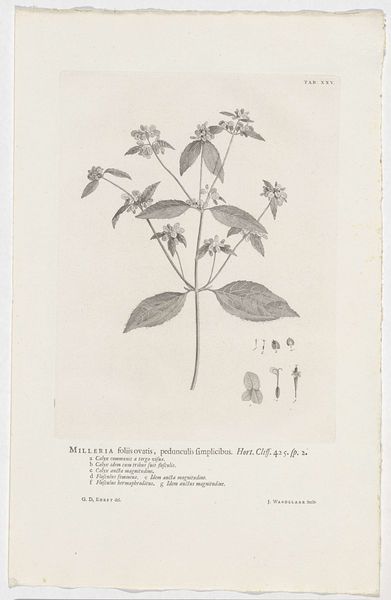

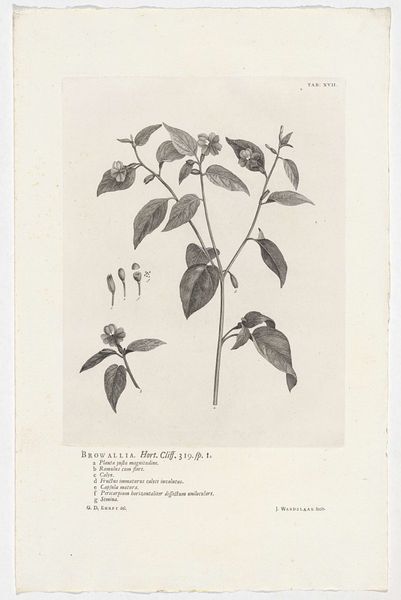

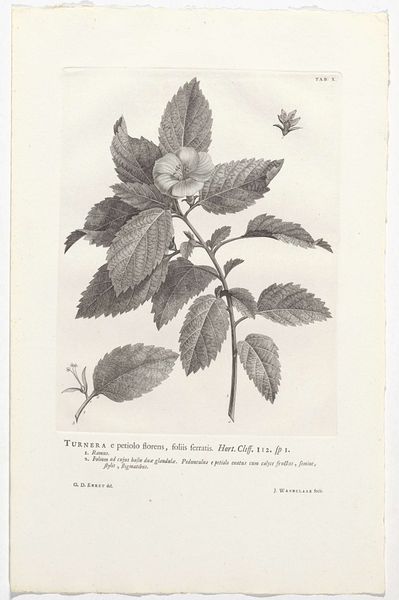

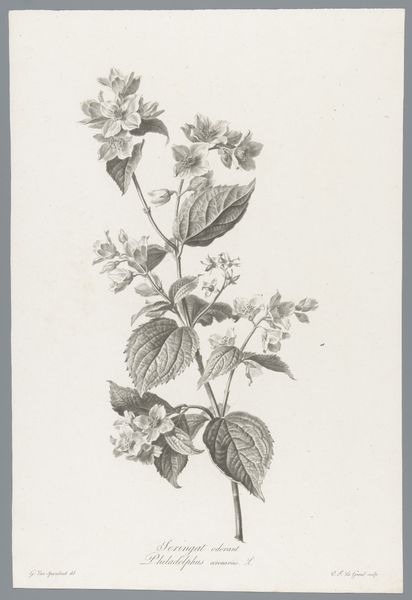

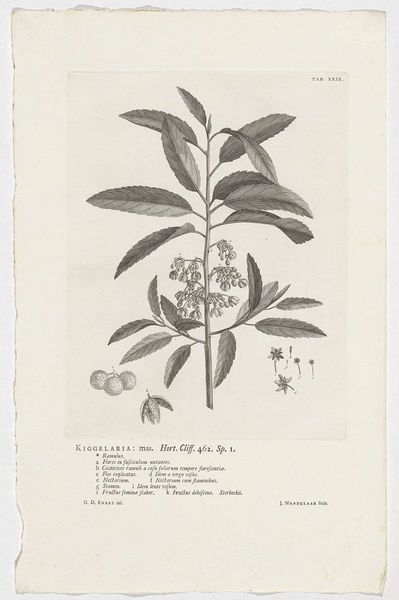

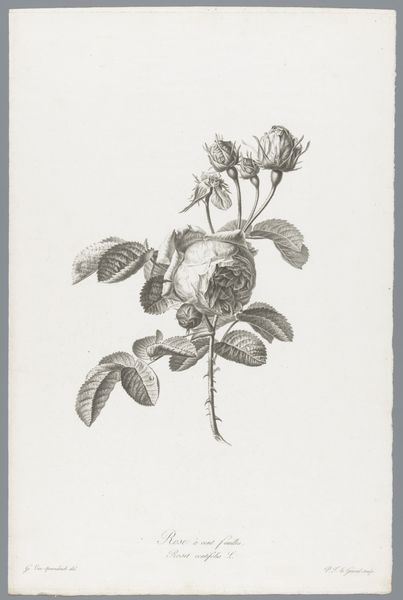

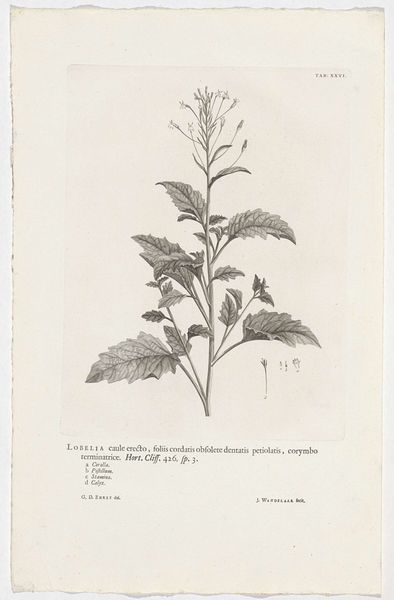

drawing, print, paper, engraving

#

drawing

# print

#

flower

#

paper

#

plant

#

engraving

#

botanical art

Dimensions: height 284 mm, width 220 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Jan Wandelaar's "Gloxinia perennis," created in 1738. It's a drawing, and also a print, an engraving, all on paper. I am really drawn to the plant, the simple beauty, but something about it seems very… restrained? How do you interpret this work, what do you see in it? Curator: I see this not merely as a botanical study but as a potent reflection of the era's scientific aspirations intertwined with colonial ambitions. Consider the Linnaean system, gaining traction then, attempting to classify and control the natural world – a project that parallels the classification and control of human populations by imperial powers. Editor: That’s fascinating! So the urge to categorize the plant life mirrored societal categorizations, sort of? Curator: Precisely. The scientific gaze itself becomes a tool of power. This seemingly objective rendering of the "Gloxinia perennis" is implicitly linked to the exploitation of resources and labor in colonized lands, resources that often funded these very scientific endeavors. What might be elided when botanical illustrations were commissioned during periods of conquest? Editor: I hadn’t considered that at all. That perhaps by recording nature, we were also in a way, claiming ownership. So, we're seeing science and art both acting as instruments, then. Curator: Absolutely. Even the act of naming and categorizing itself has a political dimension, obscuring Indigenous knowledge and alternative ways of relating to the natural world. Editor: That’s… sobering. I’ll never look at botanical art the same way again. Thanks for pointing out what's invisible at first glance! Curator: My pleasure. The deeper we look, the more connections reveal themselves.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.