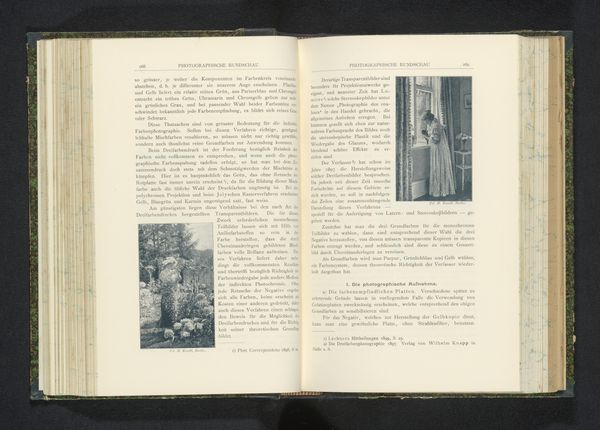

photography

#

portrait

#

pictorialism

#

photography

Dimensions: height 147 mm, width 70 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Editor: Let’s turn to ‘Portret van een onbekende vrouw met een hark en een kan,’ a photograph, likely a gelatin silver print, dating to before 1902 and made by Gottfried Wolfsgruber. It's presented in an opened book. There’s something immediately striking about the contrast between the woman's serene pose and the tools suggesting hard labor. How do you interpret this image within its historical context? Curator: What I see here is a negotiation of class, gender and the act of representation itself. On one level, this pictorialist photograph evokes a romanticized vision of rural womanhood. However, by presenting this image in what appears to be a photographic manual, Wolfsgruber perhaps inadvertently comments on the societal expectations of women's roles and the labour involved, as well as on the aesthetic aspirations of early photography. What do you think about how she is staged? Do you see any visual cues of performativity? Editor: That’s an interesting point. I hadn’t thought about the performance aspect so directly. Her clothing does seem...theatrical, like a costume. Also, why include her within a photography book? Perhaps, he’s attempting to elevate everyday lives or merge art and life? Or, instead, is there something exploitative at play, reinforcing existing social hierarchies through a seemingly artistic medium? Curator: Exactly. This photograph allows us to unpack how images can perpetuate and perhaps unintentionally question existing power dynamics. Images often reinforce what we think to know but in fact there is a hidden layer in how meaning is constructed that reflects how ideology gets expressed through everyday materials. Editor: I’ll definitely be thinking about that next time I look at early photography, especially considering how those images shaped perceptions then and continue to influence us today. Curator: Indeed. And remember, these questions are relevant across all artistic mediums, and they encourage us to understand artworks as social, political, and historical products.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.