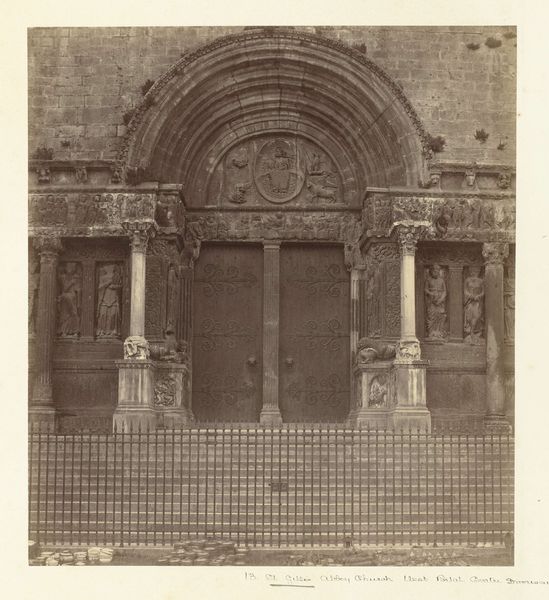

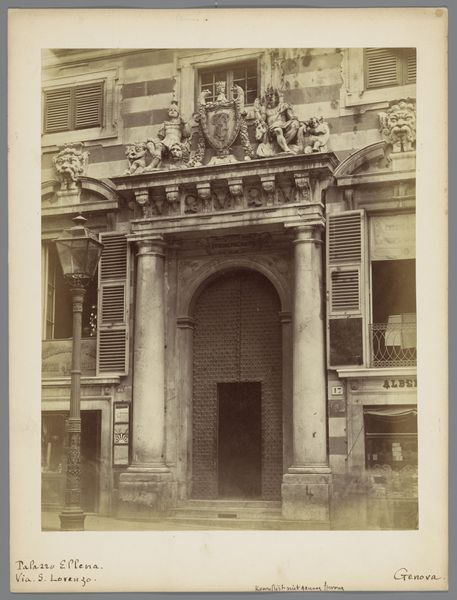

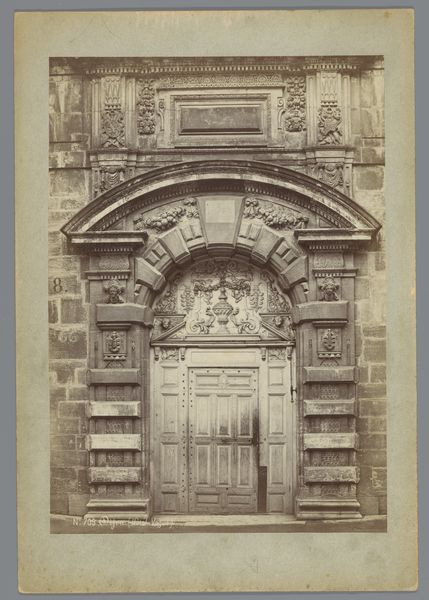

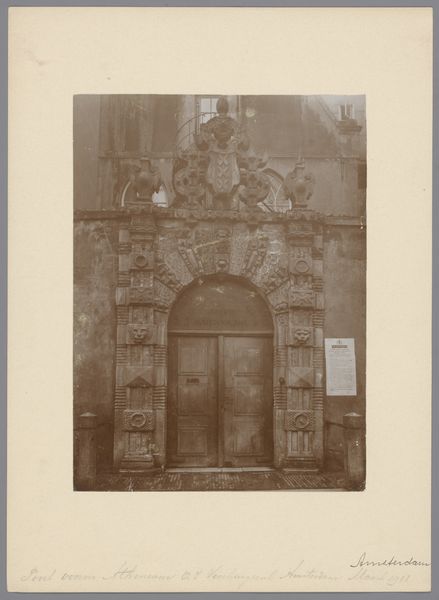

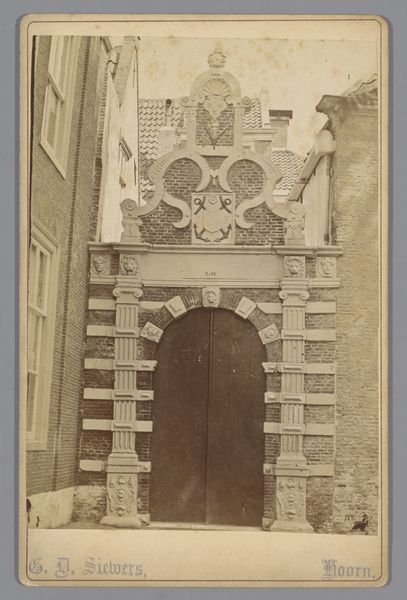

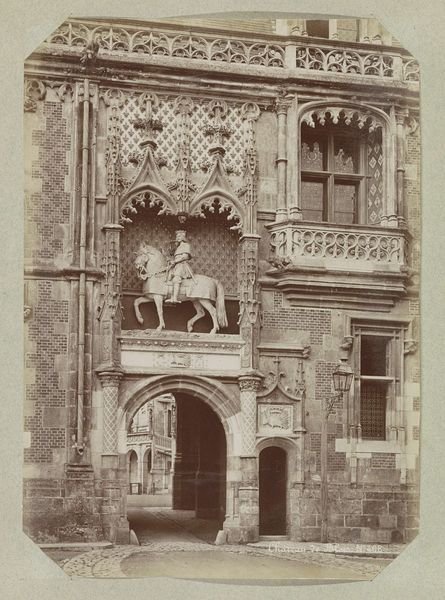

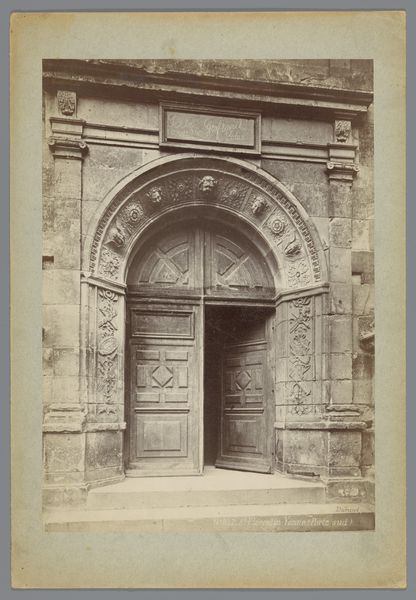

Dakkapel van het kasteel van Blois, versierd met salamander c. 1880 - 1900

0:00

0:00

medericmieusement

Rijksmuseum

Dimensions: height 354 mm, width 258 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Médéric Mieusement’s photograph, "Dakkapel van het kasteel van Blois, versierd met salamander," dating from around 1880 to 1900. It's a striking image of this architectural detail, capturing both its grandeur and, well, its age. The stone looks beautifully worn. What’s your take on this photograph, in particular, what it might be conveying about the process and context of image-making? Curator: I’m drawn to the physical processes inherent in creating such an image during this period. Think about the labor involved—mining and preparing the silver for the photographic emulsion, the precise chemistry to develop the plate, and then the printing process. Also, notice how the photographer captured this doorway, focusing attention not just on the craftsmanship of the stone carving but drawing attention to the material itself. Editor: The texture really stands out. Do you think that was intentional? Curator: Absolutely. The very act of photographing stone underscores a commitment to capturing the essence of its material existence. Moreover, consider what the choice of a solid architectural element implies— permanence. This speaks volumes about contemporary society’s consumption and values, positioning the artwork in dialogue with the material conditions that surrounded its creation and that dictate its existence. Editor: So it’s not just about documenting a beautiful doorway; it's about revealing the story embedded in the materials? Curator: Precisely. It allows us to ask crucial questions. How does the production process relate to social structures? What assumptions about craftsmanship and preservation do we bring to such an image? By interrogating these aspects, the photograph becomes more than just a pretty picture. Editor: I’m definitely seeing it in a new light now. The picture almost becomes an examination of labor, consumption, and society all at once. Thank you! Curator: It was my pleasure to encourage new interpretations and to emphasize how such imagery reflects labor and societal choices, opening critical dialogues.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.