Dimensions: height 355 mm, width 260 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

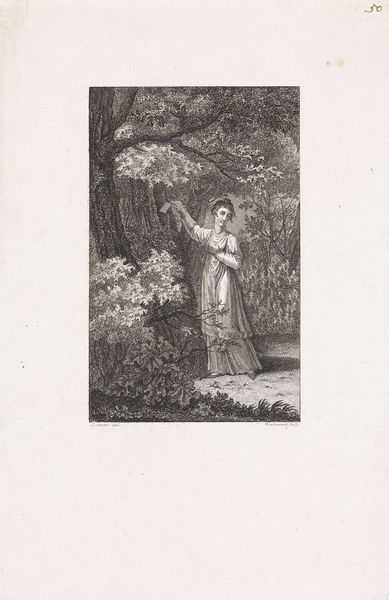

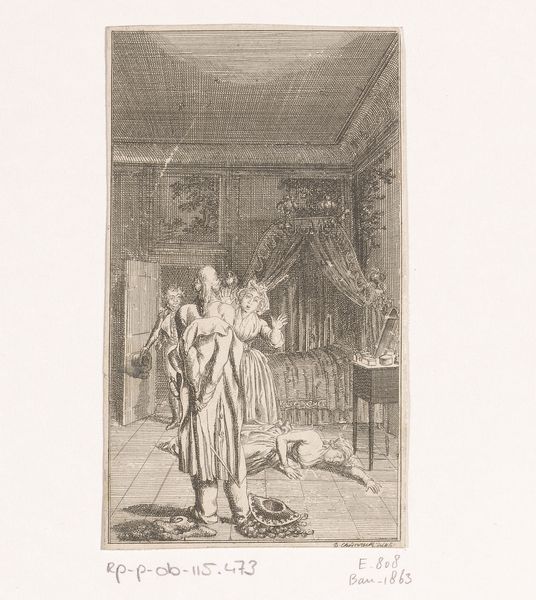

Curator: This is "Mother and Daughter at a Marian Chapel," an engraving made between 1867 and 1874, attributed to Anthony Cornelis Cramer, now residing here at the Rijksmuseum. It presents a glimpse into a seemingly intimate moment. What's your first take? Editor: Melancholy. Despite the Marian symbol, there’s an overwhelming sense of sorrow; the child's downcast gaze and the mother's wistful upward stare evoke feelings of yearning or perhaps even loss. Curator: Interesting. Viewing this through a historical lens, such displays of piety were deeply ingrained in societal expectations, particularly for women in the 19th century. The public role of women was deeply connected to domesticity and religious observance. Editor: Exactly! And examining the context of gender within 19th-century artistic production, we might also question the artist's lens here. Was this simply an accepted image, or was it actively shaping notions of femininity and devotion for viewers? Curator: It also intersects with socio-political movements of that time. Romanticism and Realism were battling for prominence; this piece strikes a chord in both camps, which helps define the social history of art through the visual arts as reflecting social tendencies, and is not separate from it. Editor: Looking closer, I see tension between the woman’s religious submission and a potential call to agency in devotion. How were women encouraged or discouraged to find power in worship? I find myself asking about the historical lived experiences and internal states of its subjects. Is she praying for change or only acceptance? Curator: And let’s not ignore how such imagery gets circulated. This is an engraving, a medium for wider distribution. So, who was the target audience? Were such depictions designed to uphold a certain moral order, especially when widely circulated in a society going through immense social upheaval and early urbanisation? Editor: Agreed. The power lies in the imagery's ability to shape viewers’ understanding of idealized motherhood and religious practice. Even a sentimental artwork such as this serves as a complex nexus of power dynamics, class, gender, and individual beliefs. It’s not just a portrait; it's a window into a specific world. Curator: Right! With its delicate details, it pulls us into a past shaped by specific institutional and societal power dynamics—influencing how people saw themselves and each other. Editor: I'm still drawn to the subdued emotion. Thinking through a lens of gender and historical narrative reveals the constraints shaping women and, perhaps subtly, hints at their hidden inner worlds.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.