print, watercolor

# print

#

caricature

#

watercolor

#

naive art

#

watercolour illustration

#

naturalism

#

realism

Dimensions: 10 3/4 x 10 1/2 in. (27.31 x 26.67 cm) (plate)

Copyright: Public Domain

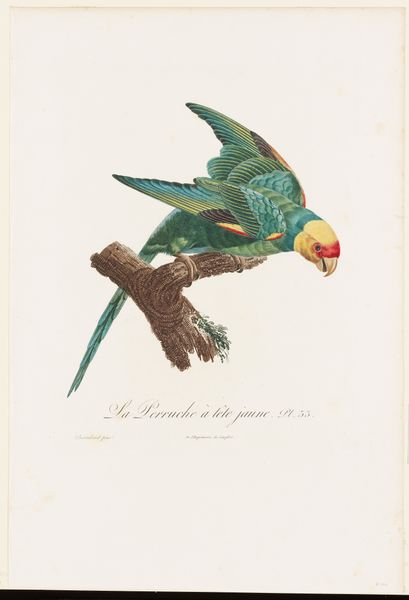

Curator: Oh, this is quite striking! Eleazer Albin’s “The Cock Macaw from Jamaica,” created between 1731 and 1738, is currently housed here at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. Albin employed watercolor and printmaking techniques to render this vibrant creature. My immediate impression is one of stately self-possession. The bird seems intensely aware of its own vivid presence. Editor: The colours definitely leap out, don’t they? The orange-red feathers contrasted with the deep blue markings… It's quite a potent symbol, I think, reflecting ideas of tropical abundance, but perhaps also colonial extraction, and power associated with such acquisitions during the era of exploration. Birds themselves are recurrent motifs, you know, for freedom, exoticism, and of course, a yearning for connection to somewhere beyond the domestic or familiar. Curator: Yes, the colours and detail serve the artist's ambition to make accurate records of newly discovered wildlife, commissioned to illustrate the natural world in a period of intense imperial expansion and the rise of scientific classification. It’s a period where illustrations played a key role in shaping European perceptions of other lands. The print format here is interesting too because it opens it up to wider consumption and circulation amongst the learned elites. Editor: The bird feels rather static, doesn’t it? Almost like a heraldic device. That deliberate stillness can imbue an image with a heightened sense of meaning and perhaps speaks to the ways birds and other 'natural' images stand as a powerful allegory for certain ideas that persist. It speaks to an impulse to possess that is always mediated, and symbolic. The way he’s depicted is almost more idea than flesh and feather. Curator: That stillness certainly does speak to how these kinds of works were often presented as scientific tools for classifying and ordering nature, part of that colonial project that brought natural history under Europe’s gaze. Editor: I do think these types of images continue to be loaded with a longing to access a deeper sense of connection, that place in us that seeks what appears beyond grasp; it has certainly traveled with our cultural history of perceiving avian images. Curator: An excellent point. It seems this macaw, frozen in time through watercolor and print, still speaks volumes about our enduring fascination with the natural world, mediated by both art and history. Editor: Yes, perhaps such objects remind us to acknowledge the emotional complexity encoded within such seemingly objective depictions of the world.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.