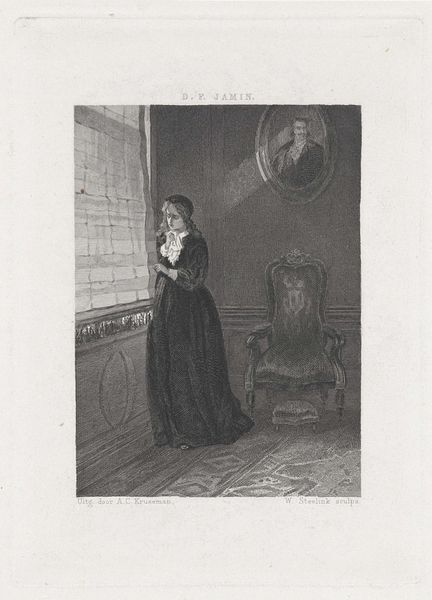

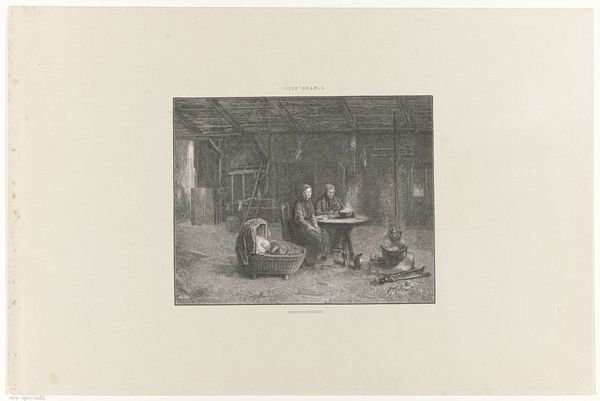

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

medieval

#

narrative-art

# print

#

vanitas

#

genre-painting

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: height 114 mm, width 178 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

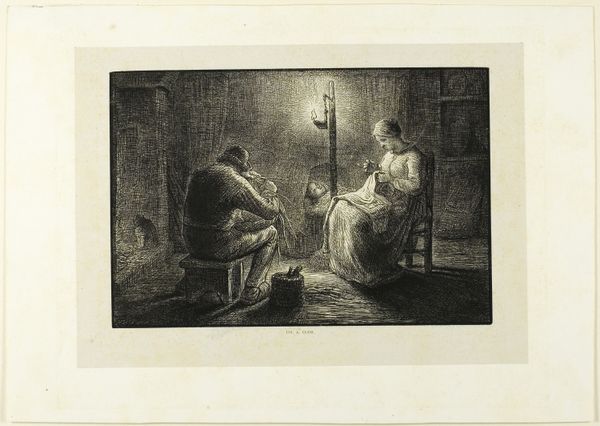

Curator: "De Lede Wieg", or "The Empty Cradle," an engraving from 1864 by Willem Steelink… It depicts quite a poignant scene. What’s your immediate reaction? Editor: A hushed solemnity. Like someone just inhaled all the air in the room, and left only grief in its place. I see such heavy resignation in the bowing woman… Curator: Absolutely. Note the realism of the style; Steelink isn't trying to pretty up this moment. It feels uncomfortably intimate, doesn't it? Consider the "Vanitas" theme, a traditional still-life reminder of life’s ephemerality. A visual elegy. Editor: Precisely! And cradles have always held profound symbolic weight. A symbol of beginnings, potential, lineage… Empty, though, the cradle becomes a void. A potent signifier of what is now lost. The room itself speaks volumes; that Delft tile on the wall behind…even that’s frozen in its domestic ritual. It deepens the absence. Curator: The positioning of the women…one slumped in the foreground, her face hidden, almost swallowed by her grief. And then the other, standing stiffly, watching her with almost awkward attention. Like grief is a spectator sport gone wrong. The empty cradle between them acts as the central focus and represents the tragedy in their presence. Editor: There's a complex interweaving of empathy and detachment, right? The woman standing seems to offer…what? Comfort? Observation? Steelink so expertly captures how loss can simultaneously connect and isolate us. And in those older styles of painting such as genre and narrative paintings, these symbols become stories in their own right, almost a silent, heart-wrenching play unfolding before us. Curator: It’s a compelling commentary on the human condition itself, the universality of loss. Engravings like this made such intimate scenes accessible to a wider audience. One wonders about the personal story behind it all, doesn’t one? It really pulls you in. Editor: Indeed, It asks you to reflect not only on what's visibly represented but on the intricate dance between objects, figures, and ultimately, our collective memory of love and lament.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.