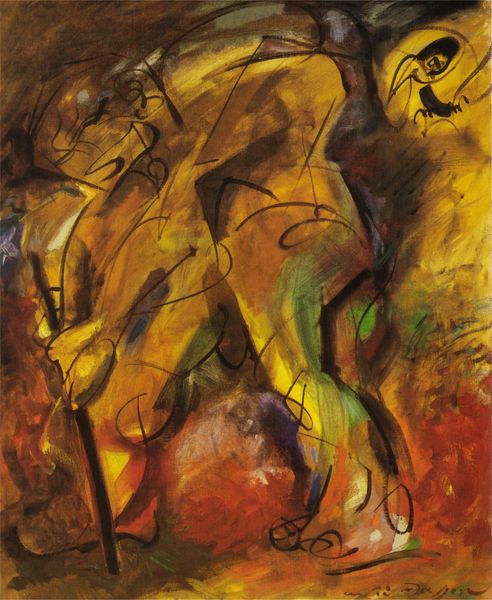

Dimensions: frame: 975 x 1180 x 78 mm support: 711 x 914 mm

Copyright: CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 DEED, Photo: Tate

Editor: This is "I Am the Abyss and I Am Light" by Charles Sims, currently residing at the Tate. The abstract shapes and the figure's posture create a really unsettling feeling. What do you see in the composition of this work? Curator: Observe how Sims utilizes contrasting colors and fractured forms. The abrupt shifts in tonality and the destabilized figure undermine traditional perspective. How does the tension between the "abyss" and the "light" manifest visually? Editor: It’s almost like the figure is trapped within the fractured shapes and colors. There is an emotional depth in the way the figure contrasts the abstract shapes. Curator: Precisely. The formal elements convey a sense of psychological struggle. The artist's arrangement suggests a breakdown of form mirroring an internal conflict. Editor: I didn't initially consider how the shapes relate to the emotional state. Curator: Considering the formal qualities enhances our understanding of its complex themes.

Comments

http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/sims-i-am-the-abyss-and-i-am-light-n04396

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.

This is one of the artist's mystical paintings which he made near the end of his life. The group of six semi-abstract paintings with figures was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1928, shortly after Sims's death by suicide, and was called by his son his 'spiritual' series. The first of them was begun in 1926, in a style which was a deliberate break with his preceding work, which had consisted predominantly of society portraits. The meaning of this work is nowhere precisely given, although its title, apparently invented by the artist and not a quotation, suggests the absolute power of God over all creation and over the destiny of the universe. It might be paraphrased as 'I am Alpha and Omega' from Revelations 1:8.The artist's unpublished papers (deposited at the Royal Academy in 1977) which give an account of his career and his thoughts about art and life, contain the passage: The use of mysticism is for comfort. when the world grows dim in old age. our senses are dulled. it is the final truth. ... Perhaps it is only in a certain ripeness that one can enter this kingdom of abstractions this epitome of Perfection as far as we know it. ... More and more divorced from particulars. Persons become Types. material becomes pattern. Incidents rhythm. Colour independent of the substance of decoration.Also in the Royal Academy archives is a defence of Sims's state of mind in the last four months of his life, written by a Mrs Younger to the President of the Academy on 20 April 1928. She gives details of Sims's ongoing work and normal behaviour, but explains that he was suffering from insomnia, for which he was taking a drug: 'I write this because people are apparently trying to keep his work out of the Academy on the grounds that he was insane, and I thought you might let it be known that he was never more normal.' Soon after Sims's death, his friend the artist Harold Speed wrote that these last paintings reflected his completely changed mood after he moved to London from Sussex in 1920: To those who knew Sims they were the most poignant expression of the anguish he was suffering ... Technically these pictures are very interesting, as an attempt at abstract form and colour expression, used legitimately to express an abstract state of mind ... All the clashing lines and jagged edges and violent colours that startle one in these pictures are not a mere meaningless whim, but a vivid expression of a tortured state of mind ... There upon canvas was his poor tortured spirit laid bare. (Speed, pp.63-4)The Tate owns one of the studies for this work (Tate Gallery T07299).Further reading:Charles Sims, ed. Alan Sims, Picture Making: Technique & Inspiration, London 1934, pp.127-30Harold Speed, 'Charles Sims, R.A.', The Old Water-Colour Society's Club 1928-1929, vol.6, London 1929, pp.62-4Terry RiggsOctober 1997