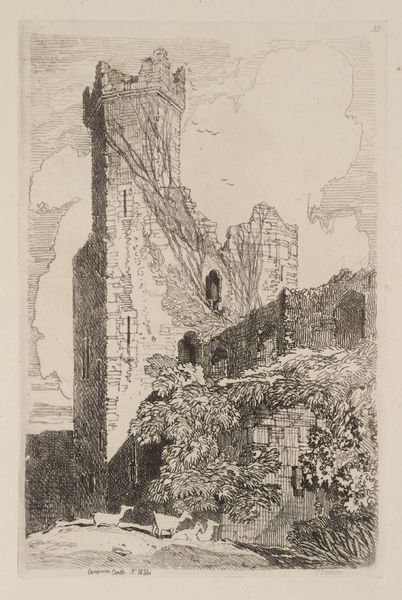

Dimensions: height 322 mm, width 235 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

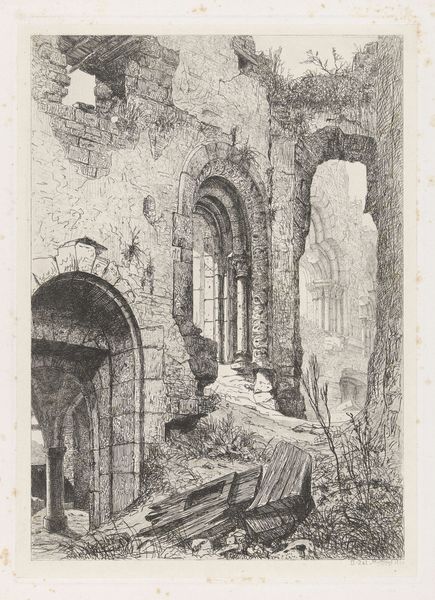

Curator: This is "Ruïne van Kasteel Feltz," or "Ruins of Feltz Castle," an etching and drawing created around 1855 by Martinus Antonius Kuytenbrouwer Jr. The work, rendered in a landscape style, depicts the remains of a historical building overtaken by nature. Editor: There’s a melancholic air hanging over this piece. It feels somber, even lonely, looking at the detailed, almost clinical rendering of these decayed stones. You can almost feel the chill of the abandoned space. Curator: Well, that’s a classic Romantic response! But I see it as speaking to the relationship between labor, architecture, and the cyclical nature of materials. Think about the physical work involved in constructing the castle originally, the lives that were implicated in its existence, and now it has become something else, reclaimed. How do social structures shape our physical environments, and how do those environments shape labor, even centuries later? Editor: Yes, the Romantic interest in ruins as a symbol of time and mortality is clear here. But, placing it within its historical moment, think about what the castle ruins might have represented to people in the 19th century: perhaps a symbol of the transience of power, or the cyclical nature of civilizations. How did political and social change shape artistic expression around national identity? Curator: I think it prompts the viewer to examine production itself: what does it mean for an artist like Kuytenbrouwer to reproduce a ruin? Is he contributing to the "romanticization" of it, or simply documenting the raw, material effects of time? And what implications did etching processes have on the wider distribution of images during the industrial revolution? Editor: That's an interesting angle. These prints, like many images circulated at the time, played a part in shaping a national narrative. This artwork invites reflection on the very nature of power and memory. Curator: True, by examining the materials and production behind this print, we uncover fascinating insights into cultural values surrounding historical objects. Editor: Absolutely. Both the print and its subject point to larger questions about how we build, commemorate, and ultimately contend with the legacies of power throughout history.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.