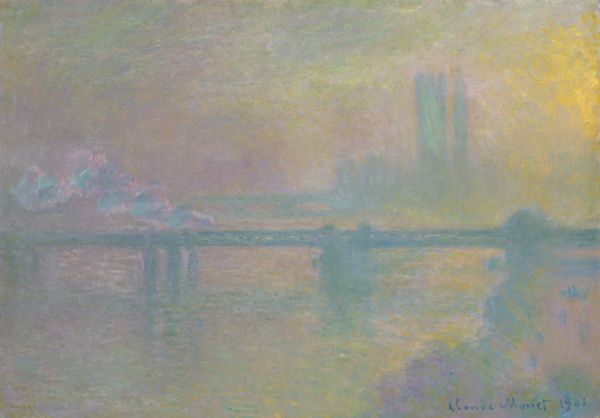

Copyright: Public domain

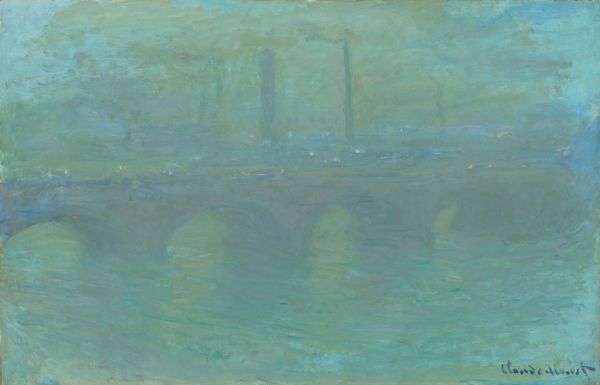

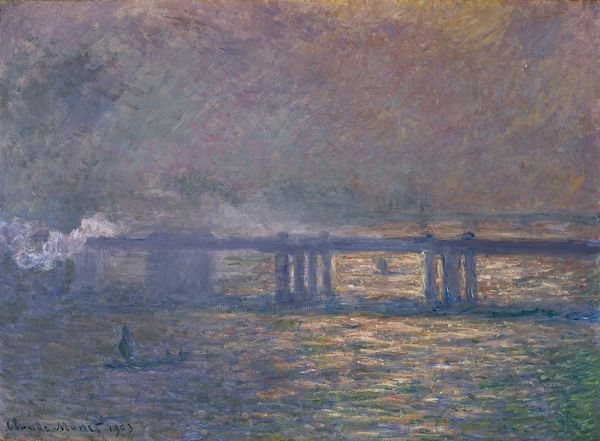

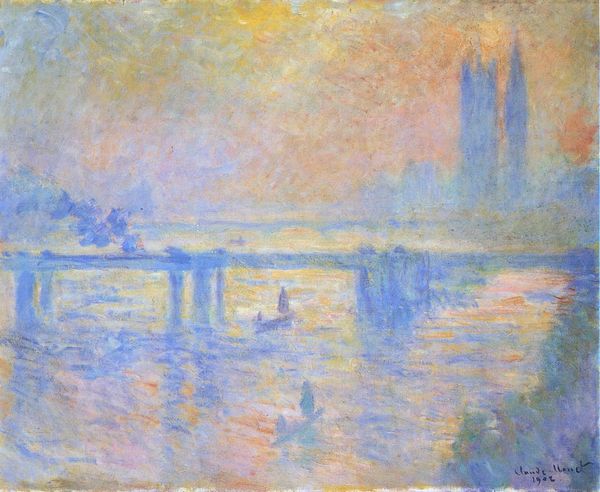

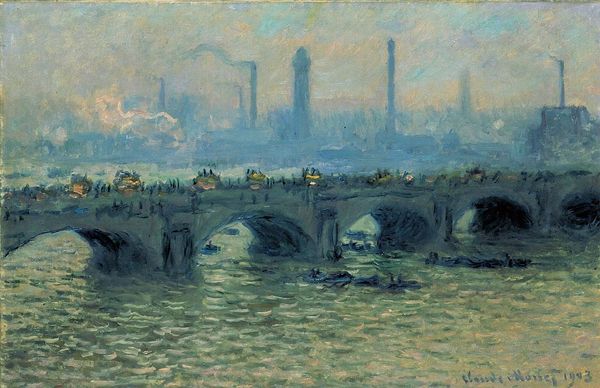

Editor: So, this is Claude Monet’s "Waterloo Bridge, London," painted around 1900 with oil paint. It's strikingly hazy; almost dreamlike, the details of the bridge barely visible. What's your take on why Monet chose to depict London in this way? Curator: Considering Monet’s interest in depicting atmosphere and light, it’s key to consider London’s socio-political landscape at the turn of the century. The Industrial Revolution meant increased coal burning, leading to notoriously thick fogs. Think of it this way: Monet isn’t just painting a landscape, but documenting the visible effects of industrial progress – the trade-off, if you will. Does this reading change how you see it? Editor: Definitely. The smog wasn't just a visual phenomenon but a consequence of specific industrial practices. It makes me wonder about the public perception of these conditions at the time. Was it seen as simply the cost of progress? Curator: Precisely. Art like Monet’s, especially when exhibited, played a role in shaping that perception. His series captured the ethereal beauty *and* the inherent pollution, contributing to an ongoing dialogue about industrialization and its environmental impact. He was exhibited and collected by influential figures - the upper class whose lifestyle was dependent on the very industry creating this atmospheric effect, in an intricate interplay. Editor: It's fascinating how a painting can reflect not only a scene but also the complex socio-economic conditions of its time. Thank you for pointing that out! Curator: My pleasure. Hopefully, next time you look at an Impressionist landscape, you might also consider what is just outside the frame, hidden by the fog!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.