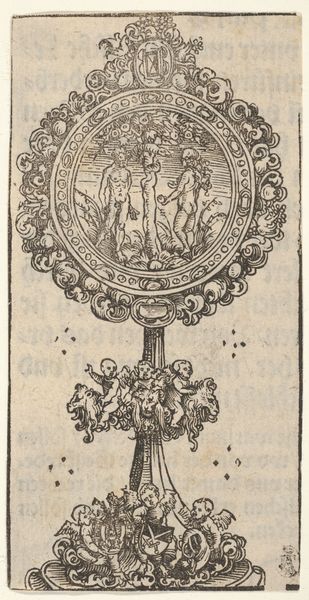

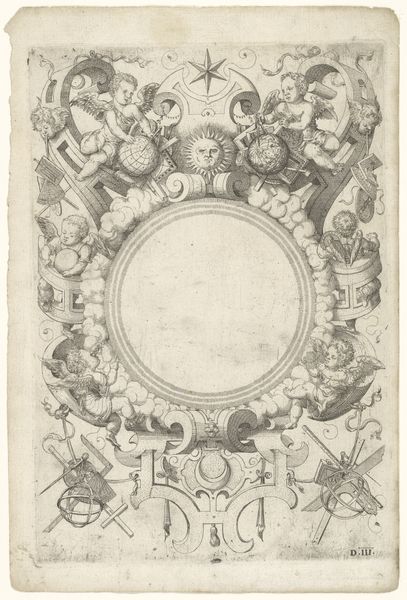

Bust of Sol surrounded by strapwork, from the series 'Deorum dearumque,' a set of images of deities after coins in the collection of Abraham Ortelius 1573

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, pen, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

pen drawing

#

face

# print

#

pen illustration

#

11_renaissance

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

pen

#

engraving

Dimensions: plate: 4 3/4 x 3 5/16 in. (12 x 8.4 cm) sheet: 7 5/16 x 5 5/16 in. (18.6 x 13.5 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: This is Gerard van Groeningen's 1573 engraving, "Bust of Sol surrounded by strapwork." It’s part of a series of deities after coins from Abraham Ortelius’s collection. I'm struck by how rigid and ornamental it feels, like a formal crest. What sort of symbolic baggage would it carry for its original audience? Curator: Notice how Sol, the sun god, is centered, literally radiating power, enclosed in this elaborate frame. Consider the persistence of solar deities across cultures; from ancient Egypt to Rome, Sol embodies life-giving energy and divine authority. It's more than just aesthetics; it’s about the symbolic language of power and continuity. Editor: So, the "strapwork" isn't just decoration then? Curator: Not at all. The strapwork—the interwoven bands—speak to connection and perhaps even constraint. Think about how a coin, the source image, itself functions. It's a controlled representation, a symbol circulated to establish value and control. This image re-presents the already-presented. It’s a copy of a coin of Sol, the divine Sun, a copy meant to underscore and legitimize power. Consider, what does that layering of representation do to the meaning? Editor: It makes me wonder about authenticity. Like, is this *really* Sol? Is it *really* valuable? Curator: Precisely! This speaks volumes about Renaissance anxieties and aspirations surrounding antiquity, and the attempt to recapture its power and glory through images, through symbolic shorthand. Editor: I never considered the layers of meaning in something that looked simply decorative. Curator: The power of iconography lies in its ability to condense complex ideas into visual form. It teaches us to decode images, not just see them. Editor: I'll definitely be looking at old coins differently now. Thanks for shedding some light!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.