Copyright: Public Domain

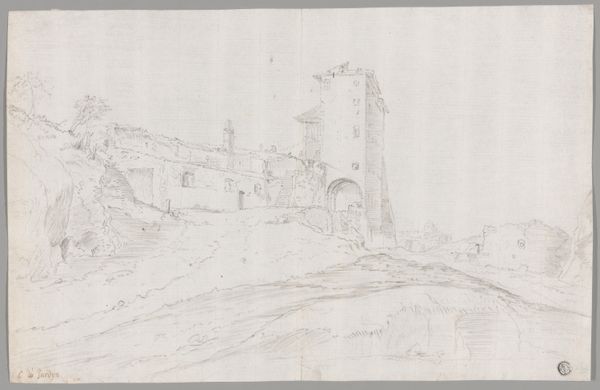

Curator: Let's discuss "Ruins near Kuum-Ombos," a pencil and etching on paper by Friedrich Maximilian Hessemer, created around 1829. It resides here at the Städel Museum. Editor: Immediately, there’s a sense of melancholy, don’t you think? A hushed silence hangs over these ancient ruins, captured in the almost ghostly, faded quality of the lines. Curator: Indeed. Hessemer, deeply influenced by Romanticism, was invested in documenting architectural marvels, and this drawing reflects that impulse. Think of the prevailing interest in Egypt at the time—the rediscovery of ancient sites fueling European imaginations. Editor: I see it as an echo of colonial gazes. Artists traveling to Egypt, documenting and possessing these landscapes through their art. What narrative of power is subtly embedded within Hessemer's seemingly innocent rendering of decay? Curator: It's undeniable that art from this period often served colonial interests, whether consciously or not. Hessemer's drawing captures a specific historical moment when European artists ventured to Egypt, driven by a desire to understand and document the architectural wonders of a distant and mysterious land. The depiction emphasizes the monumentality and antiquity of the structure, suggesting a civilization of great achievements reduced to a state of decline. This might also align with the Romantic sensibility that often viewed ruins as symbols of lost greatness, triggering thoughts on the ephemerality of human existence and the passage of time. Editor: And within this representation of decline, doesn’t there also lurk a kind of orientalism? The exoticized “other” represented as crumbling and, implicitly, awaiting rescue or interpretation by the West. I wonder what stories remain unheard because of that focus. Curator: Your points bring valuable context. While the artwork invites viewers to engage with a visual depiction, critical conversations surrounding its production should encourage the broader analysis of historical perspectives. It challenges us to see the artwork not only for what it represents but for what might have been deliberately, or inadvertently, suppressed in its visual rhetoric. Editor: Exactly! Examining how cultural narratives are visually constructed challenges viewers to consider perspectives on artwork and history. It allows us to unearth buried narratives and appreciate a richer understanding of artwork that can serve the public in our modern landscape.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.