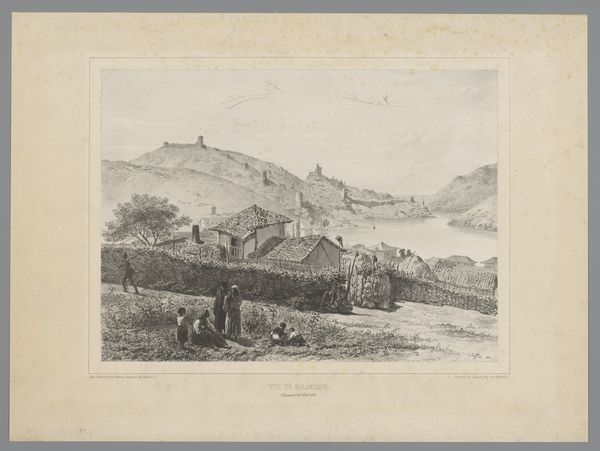

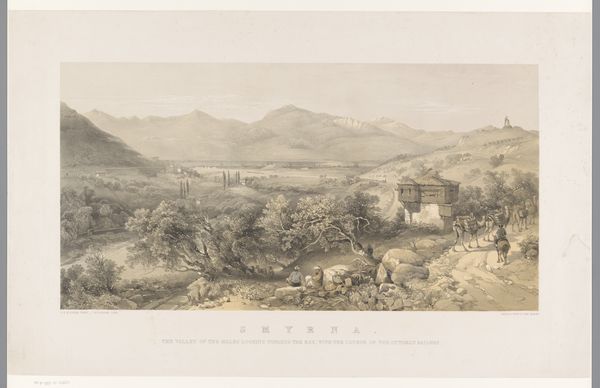

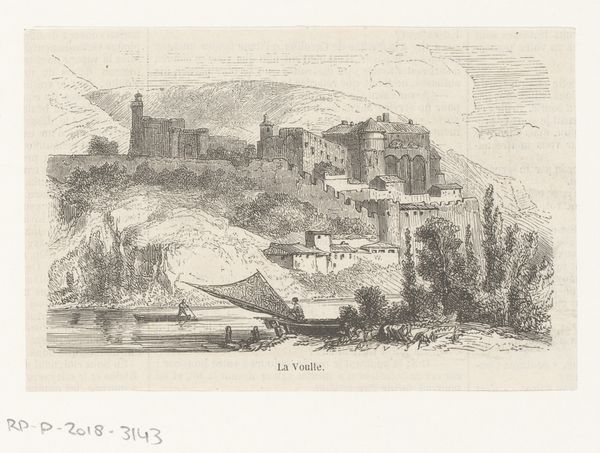

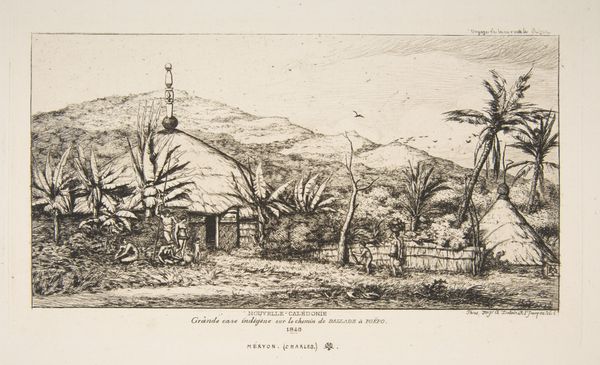

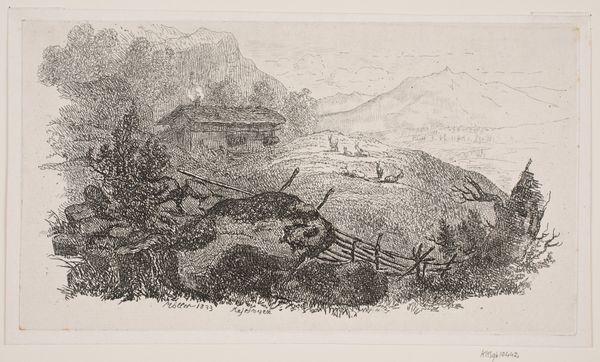

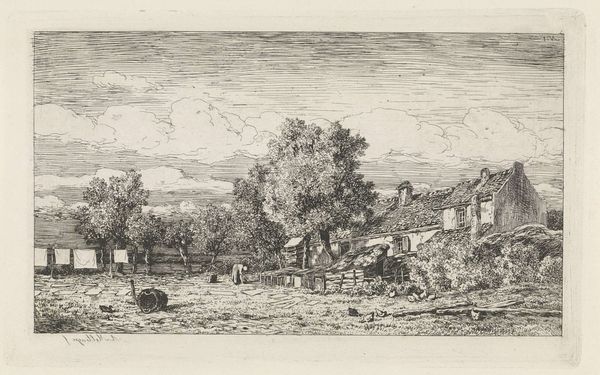

drawing, print, pencil, architecture

#

drawing

# print

#

landscape

#

romanticism

#

pencil

#

architecture

Dimensions: Sheet: 14 3/16 × 21 9/16 in. (36 × 54.7 cm) Image: 8 1/4 × 12 5/16 in. (21 × 31.2 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: So, we’re looking at Eugène Isabey’s "Royat Groove" from 1831, currently residing at The Met. He crafted it with pencil. Editor: The moment I saw this drawing, I was transported—not to any specific place, but to a feeling, that in-between space of melancholy and resilience. Curator: The Romantic movement, right? The blurring of those emotional boundaries is key. The print's composition, too—observe how Isabey uses the pencil to establish both a deep spatial recession and an almost tactile sense of the surfaces in the foreground. How do you think he uses material to reinforce meaning? Editor: Those gnarled, towering trees framing the village in the background. They feel both protective and a little ominous, don't they? It makes me think about the raw materials available, and the economy created around architecture materials—the cost versus availability, etc. Curator: Absolutely, Eugène Isabey utilizes pencil and printmaking techniques to suggest something about societal constructs within landscape. This was after the Revolution; shifts in social status influenced his choices. The ruin depicted at the center suggests those broader socioeconomic shifts and even potentially the class systems reflected even within an apparently "natural" scene. Editor: It’s interesting how Isabey chose this particular village, Royat, and how his drawing might contribute to or challenge perceptions of rural life in early 19th-century France. Do you see the composition or line work differently when considering those potential class themes and romanticism? Curator: Definitely. I’m drawn to how labor processes can intersect with representation. The medium becomes active, mediating what is prioritized, erased, highlighted, and ultimately believed or ignored as the “truth” of this scene. Editor: It is like memory, where the landscape softens edges to allow meaning-making—our romantic lens of perception. I leave with a little piece of Isabey's imagined France in my pocket. Curator: Exactly—thinking about our engagement with the artwork reveals truths. This process is never truly “over,” as the layering of interpretation will continue onwards!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.