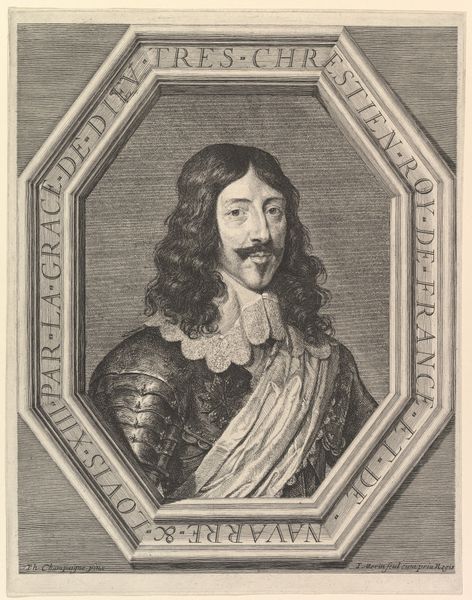

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

engraving

Dimensions: 410 mm (height) x 302 mm (width) (plademaal)

Editor: This print, titled "Frederik III," dates back to sometime between 1646 and 1649. It's an engraving and belongs to the Statens Museum for Kunst collection. It feels like a very official depiction, quite serious. I'm curious, looking at this image, what aspects stand out to you, especially concerning its place in history and the institutions that have shaped its viewing? Curator: It's interesting that you pick up on that sense of officialdom. Portrait engravings like this were vital instruments of power. Before photography, how else could a monarch project their image? This wasn't just about likeness; it was carefully constructed propaganda, disseminated widely. Notice the armor – a statement of military might, though likely Frederik III spent more time in council chambers than on battlefields. Editor: So, it’s less about realism and more about communicating a specific message? How much control would Frederik III have had over this portrayal, and its circulation? Curator: Immense control. Everything from his pose to the elaborate text surrounding the portrait would have been carefully considered, crafted to cultivate a specific public perception. Think about the institutions involved: the monarchy needing to legitimize its rule, the printmakers reliant on royal patronage, and ultimately the consumers, the public whose opinions these images were designed to influence. Do you notice how the baroque style and the print medium contribute to this feeling? Editor: Definitely! The intricate details feel opulent, suggesting wealth and authority, while the print medium allows for mass distribution. It’s fascinating how the very nature of the artwork—as a reproducible image—served a political function. Now I wonder how his image evolved, and how later rulers manipulated similar media. Curator: Precisely! The visual language of power evolved, but the underlying dynamics of image, control, and public perception remain remarkably relevant, even today. These historical echoes can prompt us to think about how power presents itself through today’s media. Editor: That makes me consider portraiture in a completely different light. Thanks! Curator: My pleasure! I, too, find myself thinking more carefully about art, its public role, and politics of representation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.