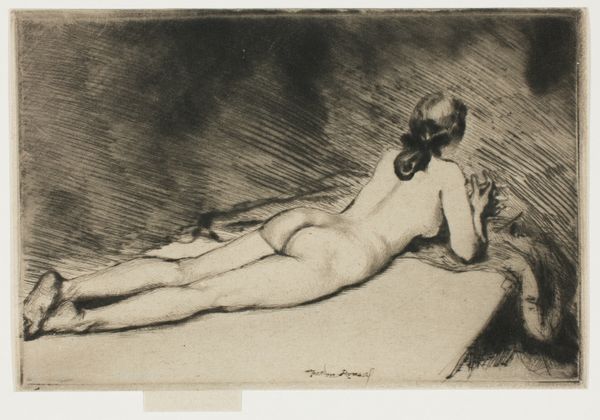

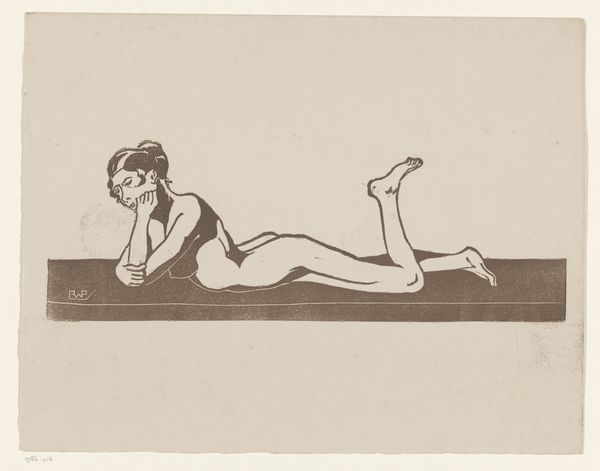

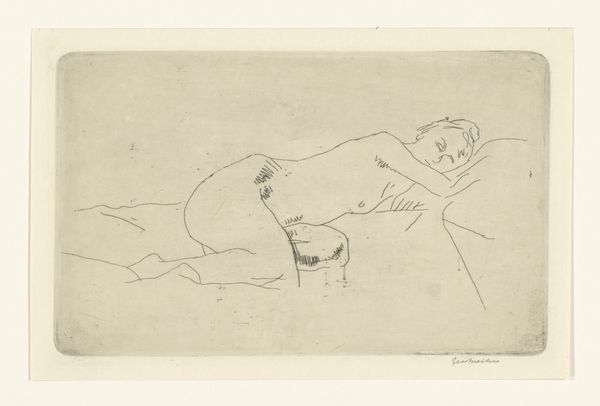

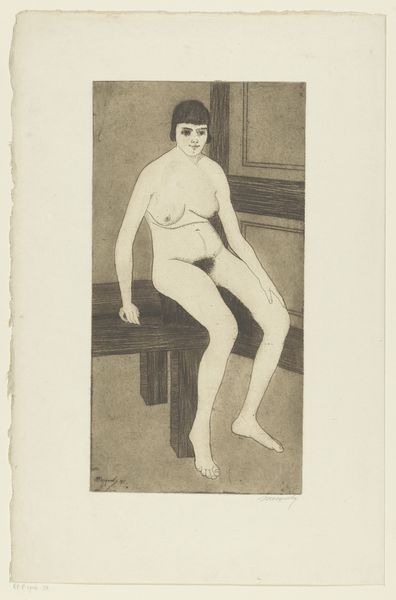

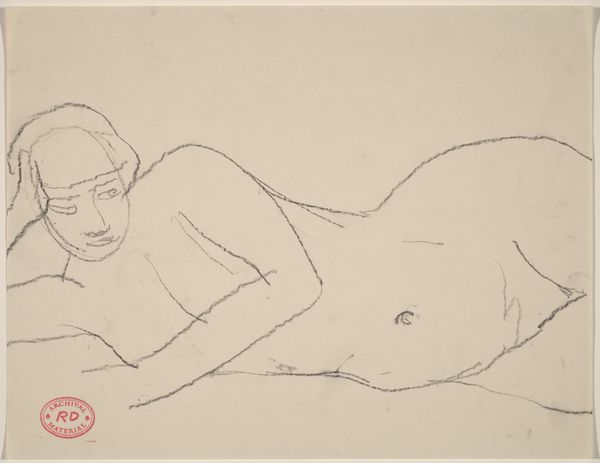

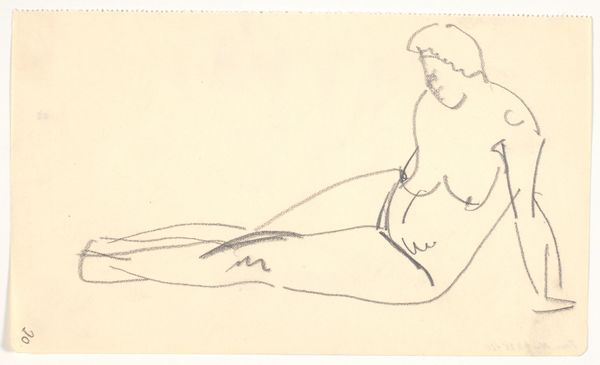

Klein liggend vrouwelijk naakt (Liggend naaktfiguur) 1917

0:00

0:00

samueljessurundemesquita

Rijksmuseum

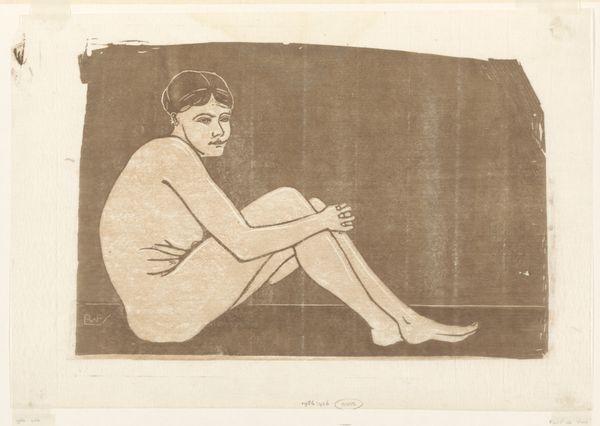

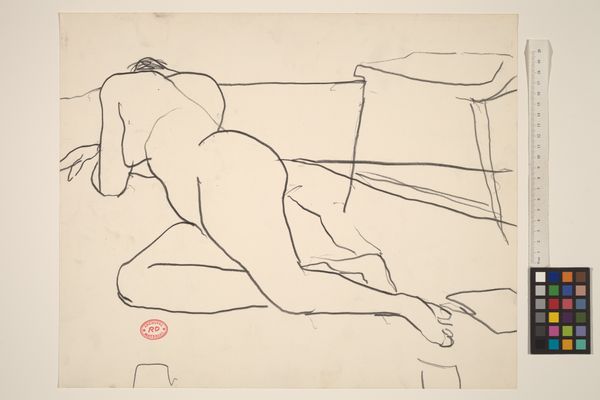

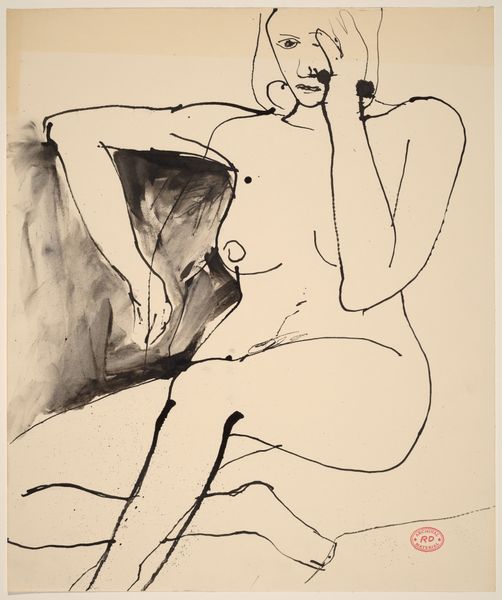

drawing, print, ink, woodcut

#

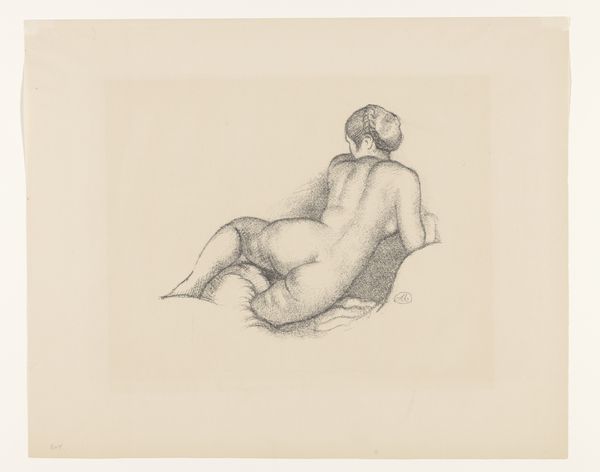

drawing

#

blue ink drawing

#

childish illustration

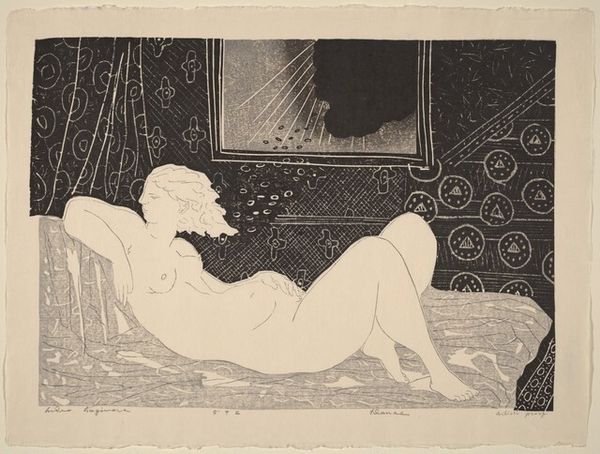

# print

#

figuration

#

ink

#

expressionism

#

woodcut

#

nude

Dimensions: height 88 mm, width 164 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have "Klein liggend vrouwelijk naakt," or "Small Reclining Female Nude," a 1917 woodcut print by Samuel Jessurun de Mesquita. It's currently housed right here at the Rijksmuseum. What are your first thoughts on encountering this work? Editor: Stark. The sharp contrast between the black ink and the paper is immediately striking. It's also a powerful pose—intimate yet detached. There's a tension between vulnerability and a sort of stoic presence. Curator: That tension definitely reflects the sociopolitical climate of the time. Expressionism was surging in popularity, partly fueled by anxieties around World War I. The nude form itself has, of course, always been a contested space in art history, used to convey power, sexuality, and mortality. Editor: Right. And you can see Mesquita really working with the materiality of the woodcut itself. The grain almost becomes part of the composition, creating texture in the background and suggesting the rough surface she's lying on. It looks quite physically demanding to create. It's about labor and the artist’s hand present in every mark. Curator: Indeed. Consider the radical shift Mesquita and other expressionists promoted. Academic tradition held up idealized forms, but Mesquita is almost anti-ideal. The face is direct, but almost mask-like and unsettling. It breaks sharply with prevailing cultural norms regarding the female nude. Editor: The simplicity adds to that unsettling effect. He’s stripped away detail to lay bare the essence of the figure. I’m wondering what kind of tools he was using—the precision required to cut those fine lines into the wood is amazing, the transfer of labor and thought into material outcome, quite profound. Curator: This was a transformative period for printmaking. Artists began embracing the medium's unique characteristics, moving away from trying to mimic painting or drawing. Works like these played a pivotal role in challenging accepted norms of taste and artistic production. It offered greater opportunities to artists who sought an affordable and relatively speedy method of creating multiple originals, extending its socio-political impact further into the masses. Editor: Well, I came in with a primarily material read of the image, thinking about production. But you've helped contextualize how that material process, and even the figure within the image, are entangled within a larger social and political world. I appreciate how the artist wielded the stark materiality and the woodcut form itself to disrupt and interrogate expectations. Curator: And I have developed a newfound respect for how labor and method speak to, but also push back against, artistic expectations from seeing this alongside you.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.