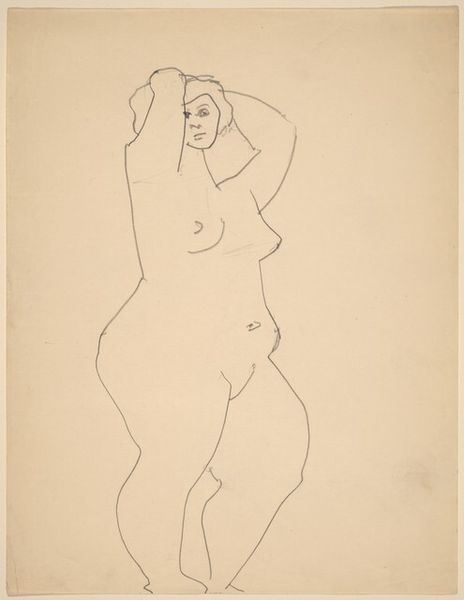

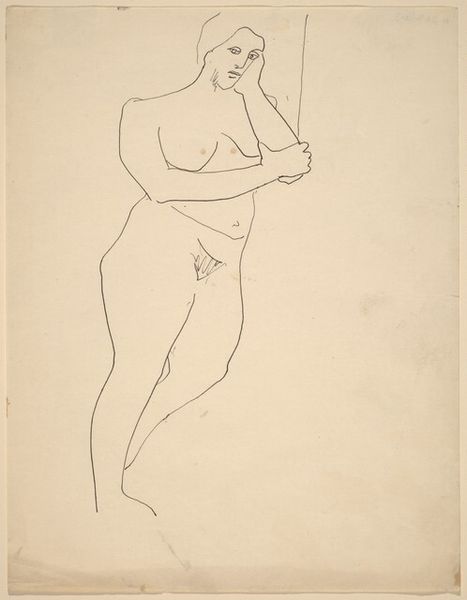

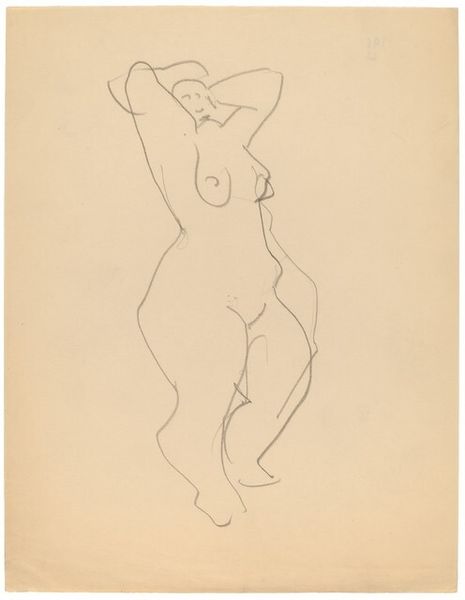

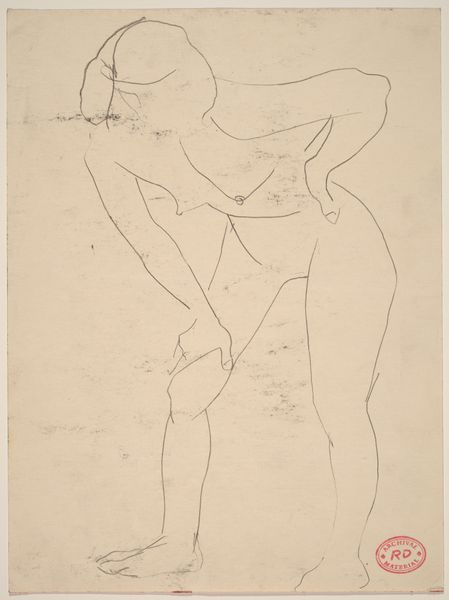

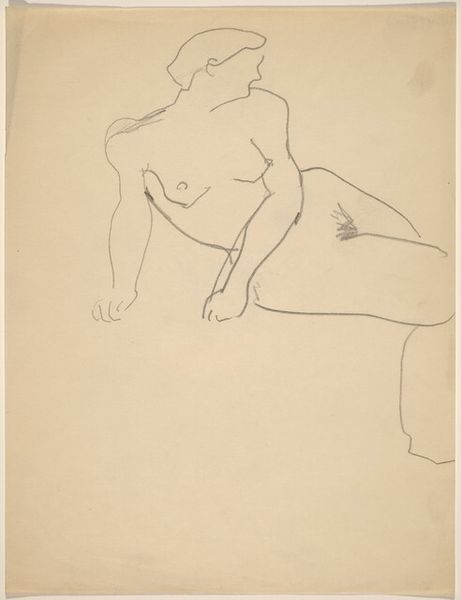

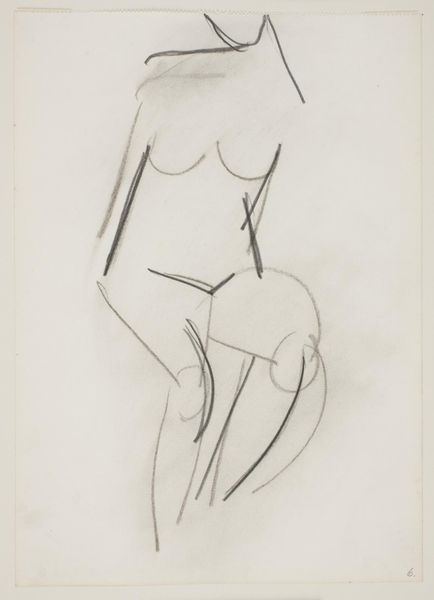

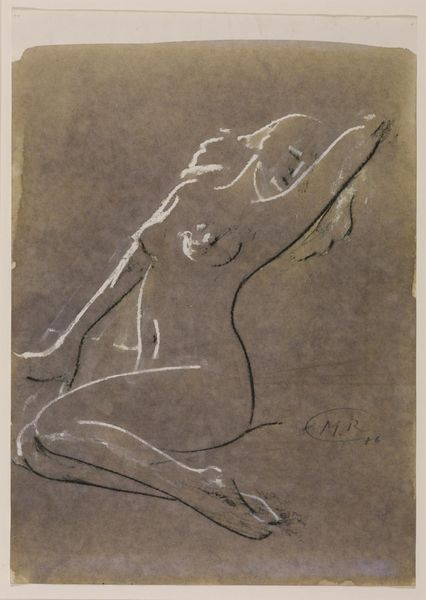

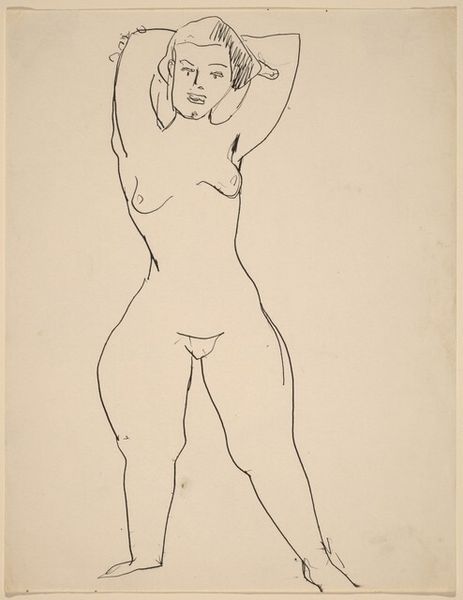

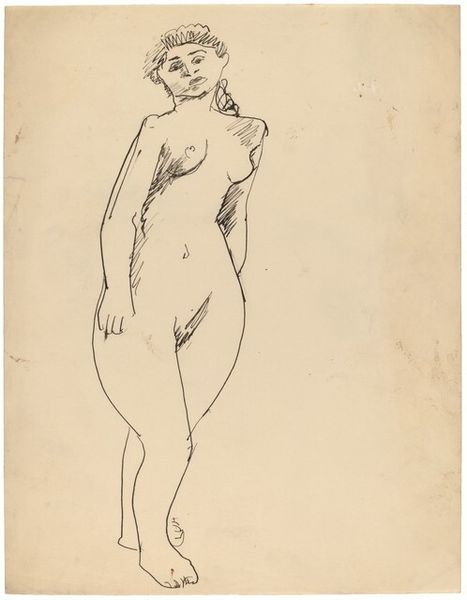

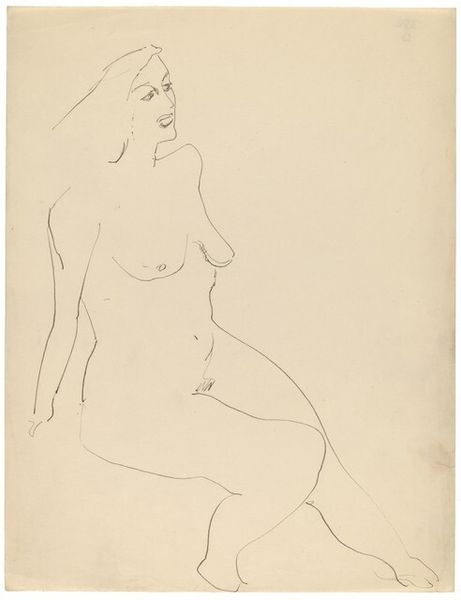

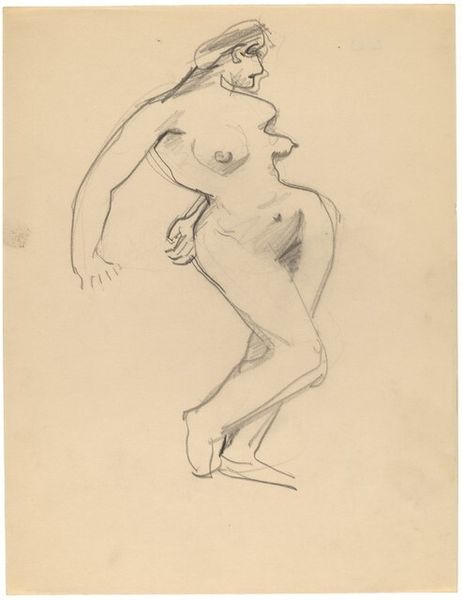

Dimensions: image: 307 x 196 mm

Copyright: © Tate | CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 DEED, Photo: Tate

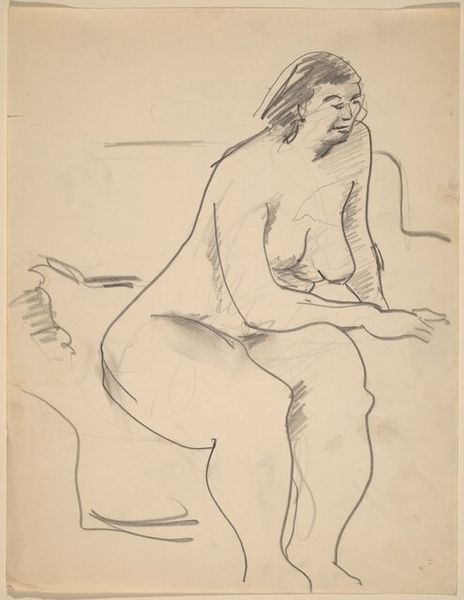

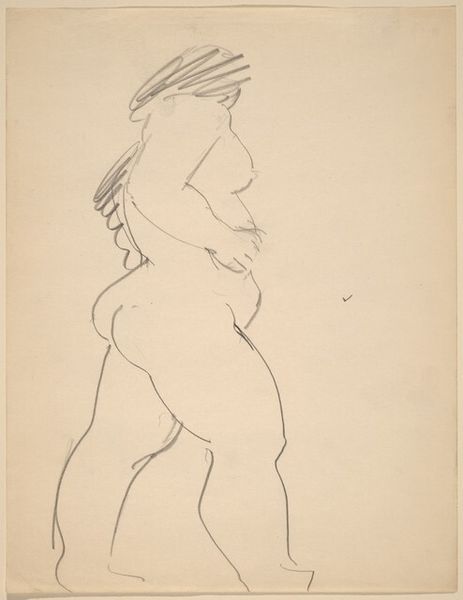

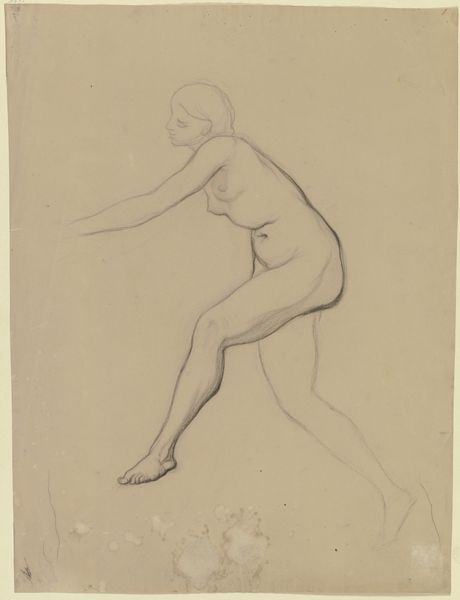

Curator: Cecil Collins created this drawing, "Seated Nude," in 1979. It's held here at the Tate. What strikes you first about it? Editor: The simplicity. It feels both delicate and powerful. The figure's pose is confident, yet there's also a vulnerability in the averted gaze. Curator: Collins was deeply interested in Romanticism, seeing art as a vehicle for spiritual expression, so perhaps that's reflected in the composition. Editor: Absolutely. We must contextualize this within the prevailing attitudes toward the female form and who has the power to capture and objectify it through their gaze. Curator: Collins’s nudes often convey a sense of universality, stripping away specific identity to focus on the essence of the human form. Editor: Yet, even in this abstraction, the drawing evokes complex discussions surrounding representation and the male gaze in art history. Curator: It's a reminder that art, even in its apparent simplicity, carries layers of meaning. Editor: Indeed. It's about questioning the power dynamics inherent in viewing.

Comments

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.

tate 9 months ago

⋮

Collins pursued his vision of a lost paradise, destroyed by the mechanisation of the modern world, throughout his lifetime. Creating his own versions of archetypal figures, such as the Fool and the Angel, he attempted to reveal to us our innermost selves. These figures, he believed, represented an innocence that had ceased to exist in the ‘Machine Age’ (Keeble, p.73). Many of Collins’s aims and beliefs were promoted in an essay he titled The Vision of the Fool which was first published in 1947. This essay, written during World War II (1939-45), affirmed the importance of the divine imagination, and has led Anderson, amongst others, to claim that Collins is the ‘most important metaphysical artist to have emerged in England since Blake’ (Anderson, p.11).