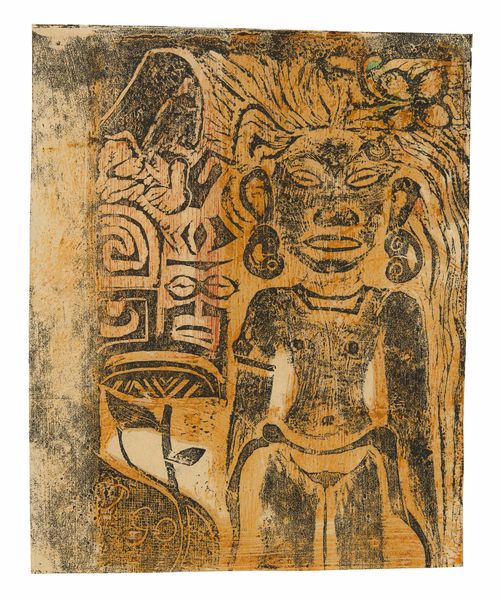

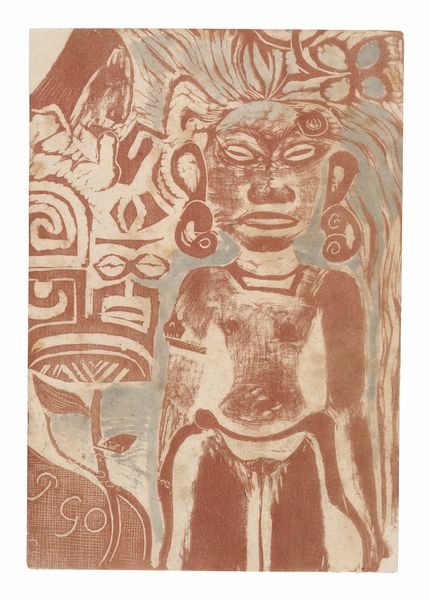

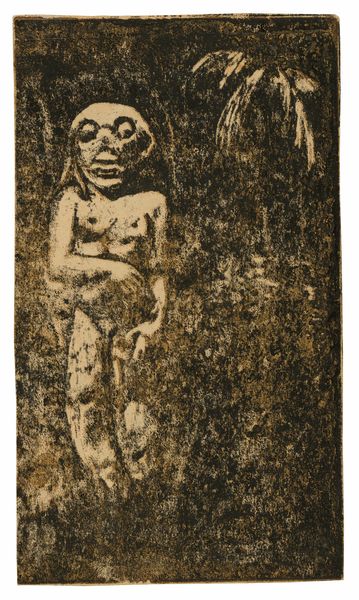

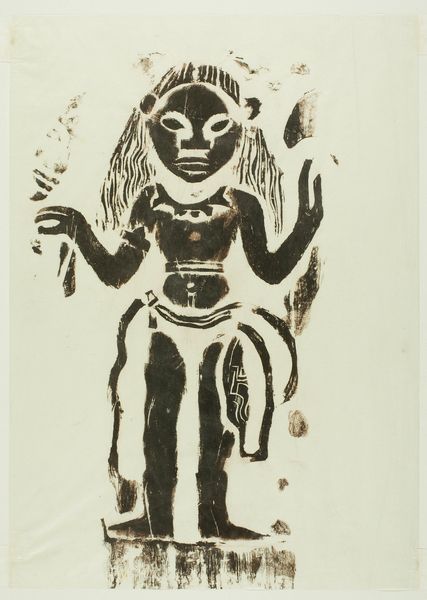

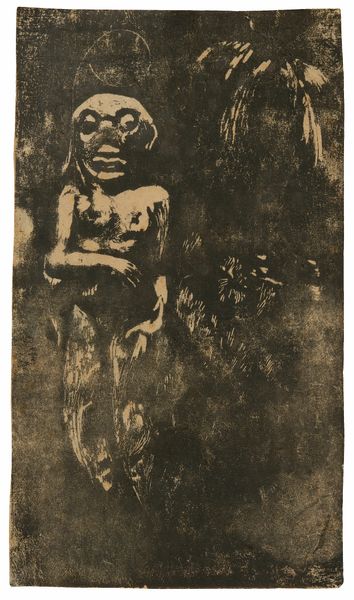

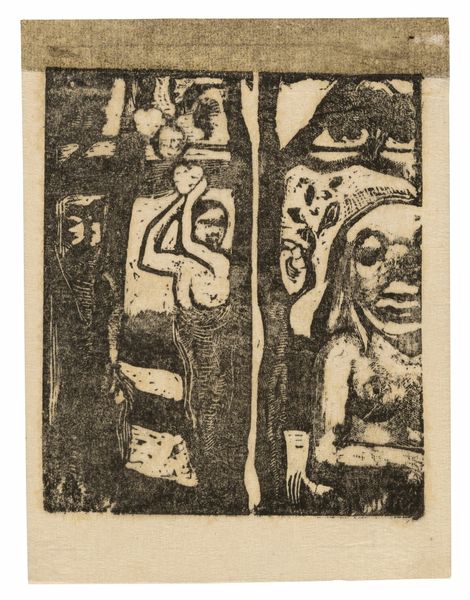

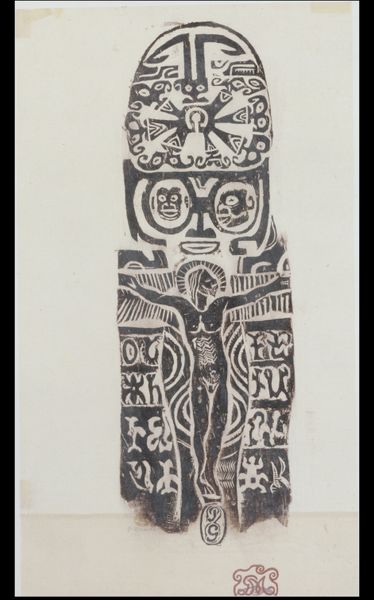

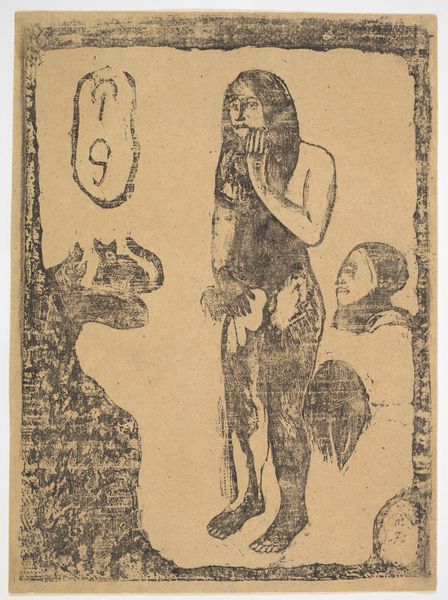

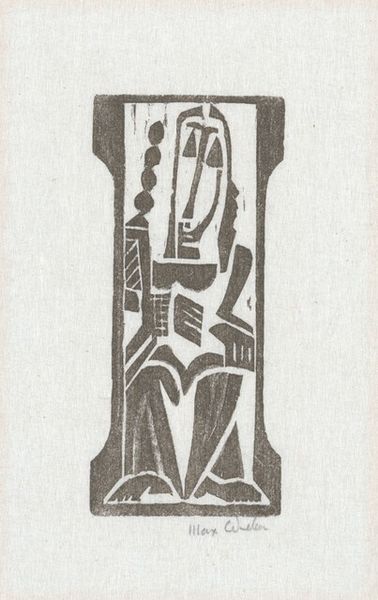

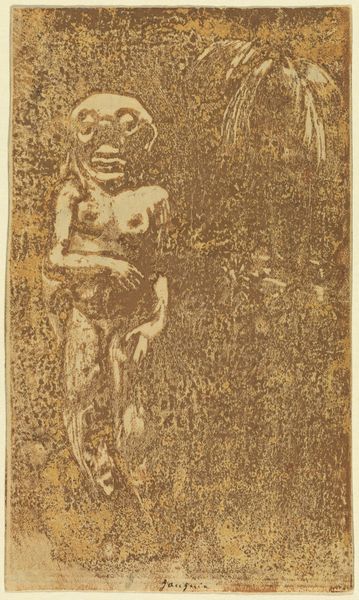

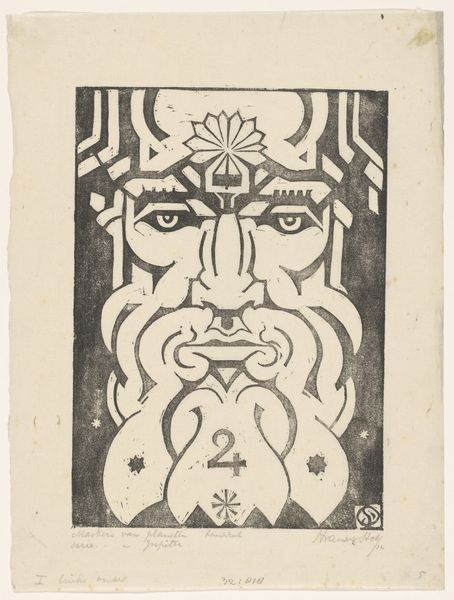

print, paper, woodblock-print, woodcut

#

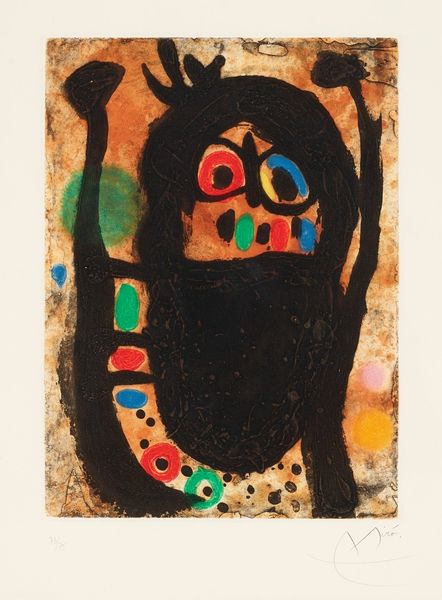

portrait

#

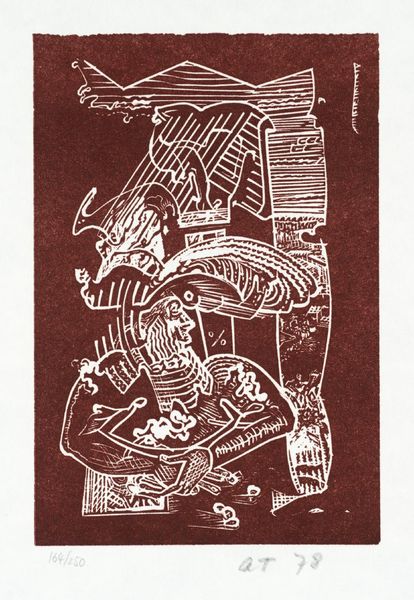

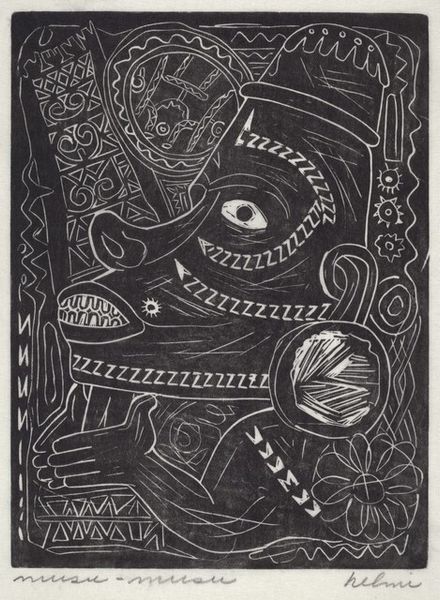

linocut

# print

#

figuration

#

paper

#

linocut print

#

woodblock-print

#

woodcut

#

naive art

#

symbolism

#

post-impressionism

Dimensions: 148 × 119 mm (image/sheet)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Just look at the arresting visual power of Paul Gauguin's woodcut from 1894-95, "Tahitian Idol—the Goddess Hina," currently housed here at the Art Institute of Chicago. The stark contrast immediately grabs your attention. Editor: Yes, the high contrast really sets the mood. It feels… primal, almost urgent, doesn’t it? The figure dominates, but the whole composition leans toward the raw materiality of the printing process. Curator: Absolutely. You have to remember Gauguin's interest in non-Western art, particularly his appropriation of Polynesian imagery during his time in Tahiti. How this "primitive" style offered, to him, an antidote to what he perceived as the over-refined conventions of European art. Think about the economics of art production in fin-de-siècle France compared with this… imagined, almost mythical production. Editor: It’s fascinating to trace those cross-cultural connections, particularly through the flattened perspective and strong outlines—almost like cloisonnism. There’s a simplification of form at play, wouldn't you agree, allowing the geometric and almost totemic symbols on the left of the composition to stand out. Also, how does the type of paper support and augment its expressive and formal presence? Curator: Precisely. Gauguin uses those lines to flatten the picture plane but also to express a certain spiritual depth, drawing from his interpretations—perhaps misinterpretations—of Tahitian culture and beliefs about Hina, the lunar goddess, the divine feminine, perhaps as a reaction against the rigid norms imposed by colonization and consumption of native culture in his period. What would you say, how his choice of woodcut, a less "refined" medium, contributes to this visual vocabulary? Editor: For sure, the roughness and textural quality of the woodcut reinforces the feeling of something "untamed," far from the academic salon. There’s an honesty in the printmaking, revealing the process itself—the carved lines, the ink, the paper. Curator: A kind of "anti-aesthetic," maybe? Gauguin critiqued academic structures through embracing materials that were available and inexpensive as part of an alternative cultural and financial structure. The art world establishment pushed back against that. Editor: In a way, then, this image operates almost like a manifest, pushing viewers toward its primal and intrinsic power through this lens. Curator: And through considering it through material and social avenues, as well.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.