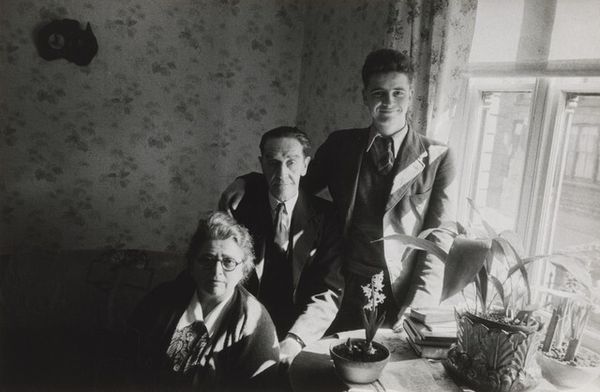

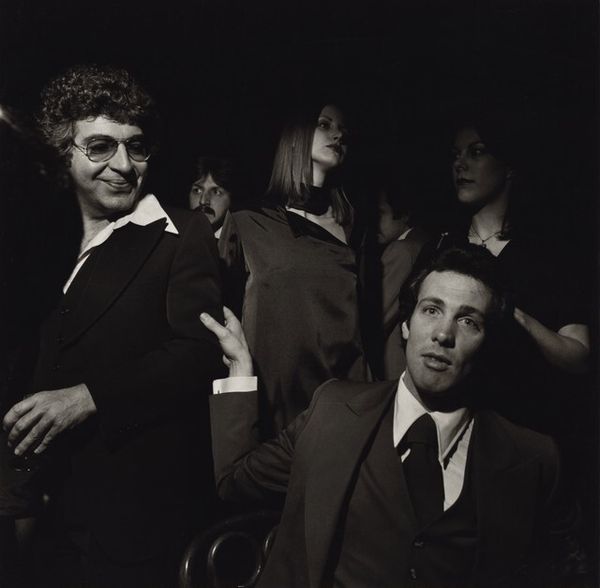

George and Edith Rickey with sons Stuart and Philip, East Chatham, New York 1973

0:00

0:00

photography

#

portrait

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

group-portraits

#

ashcan-school

#

modernism

#

realism

Dimensions: sheet (trimmed to image): 17.8 x 24.1 cm (7 x 9 1/2 in.) mount: 43.1 x 35.5 cm (16 15/16 x 14 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

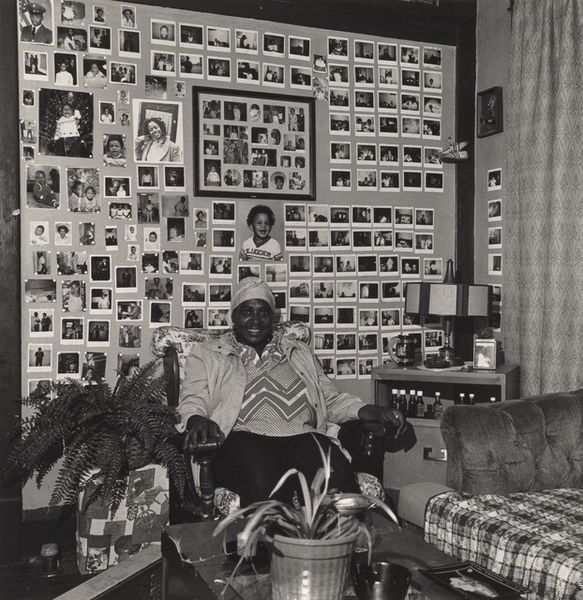

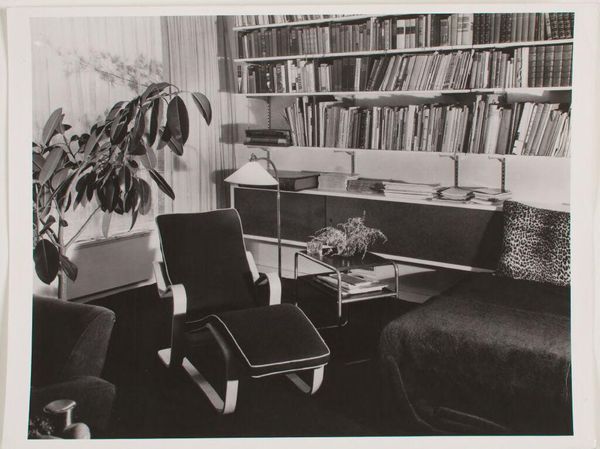

Editor: Here we have Arnold Newman’s photograph from 1973, “George and Edith Rickey with sons Stuart and Philip, East Chatham, New York.” It's a black and white shot, seemingly quite intimate. What strikes me is how their surroundings, the books especially, seem to define them just as much as their faces do. What do you see in this piece? Curator: This is an important work when thinking about the politics of representation within artistic circles. Newman's portraits often aimed to capture the essence of his subjects through their environment. In this context, consider the cultural capital represented by all those books. Who has access to such resources? Who gets to be framed by them? Editor: So, you're saying it's not just a portrait of a family, but a statement about privilege? Curator: Precisely. The Rickeys were part of a specific artistic and intellectual milieu. Think about the history of portraiture: who traditionally got their portrait painted? Usually it was the wealthy and powerful. Newman's environmental portraits update this tradition for a modern, potentially more democratic era, but the underlying dynamics of power and representation still need unpacking. Editor: It makes me wonder about their expressions, they all look very contained. Is that part of this statement too? Curator: It absolutely could be. Consider how the family chooses to present themselves. Is it genuine? Is it performative? Does the Ashcan style try to blur this divide by suggesting an unedited snapshot into a social reality, in opposition to contrived set-ups? These choices contribute to the overall message about who they are and their position within society. How does it compare to other family portraits from the same era that feature working class subjects, or people of color? Editor: I hadn't thought about it in that way before. Now, I see how a simple family portrait can open up a conversation about access, representation, and the subtle ways privilege operates. Curator: Exactly. By questioning the context, we reveal the social constructs at play within the image and maybe even challenge our own assumptions.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.