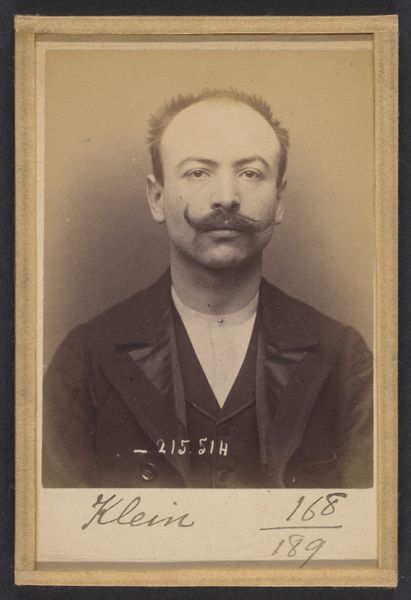

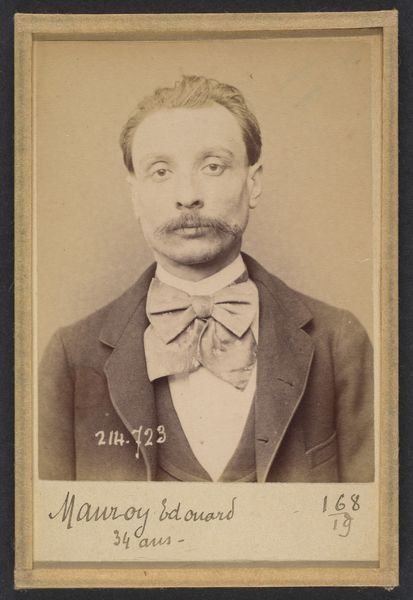

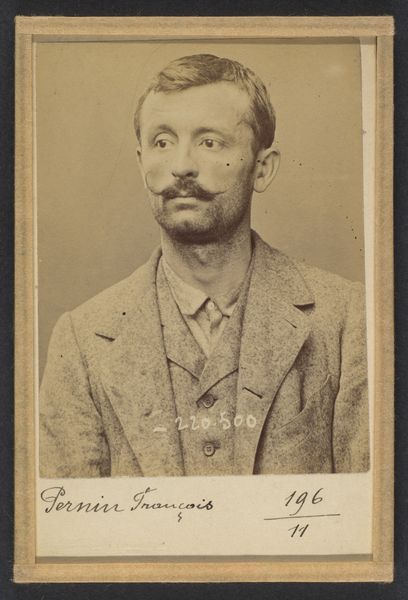

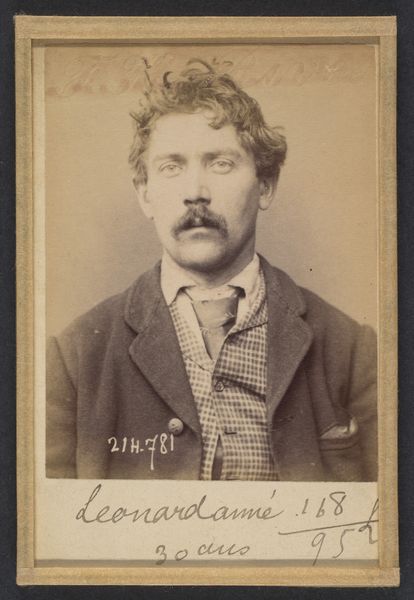

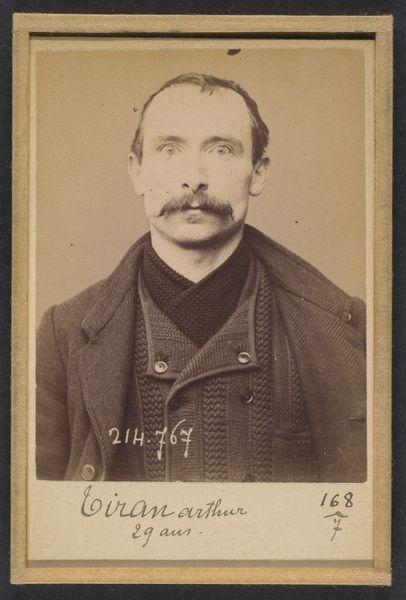

Notelez. Charles, Émile. 29 ans, né à Paris XXe. Portefeuilliste. Anarchiste. 26/2/94. 1894

0:00

0:00

photography

#

portrait

#

portrait

#

photography

Dimensions: 10.5 x 7 x 0.5 cm (4 1/8 x 2 3/4 x 3/16 in.) each

Copyright: Public Domain

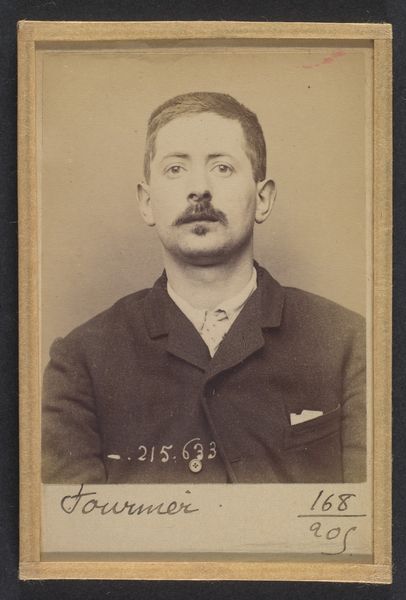

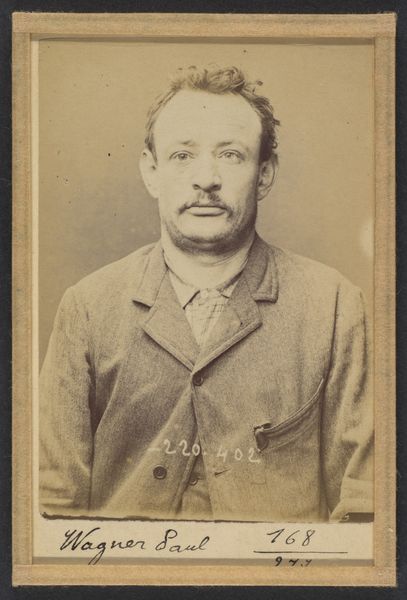

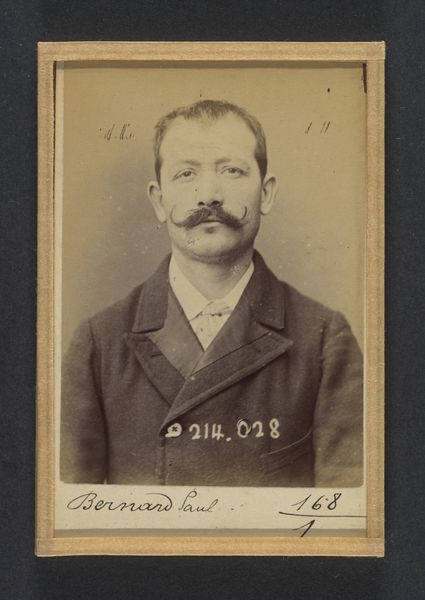

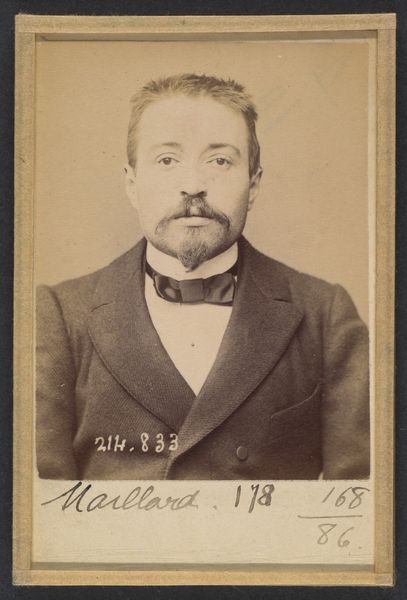

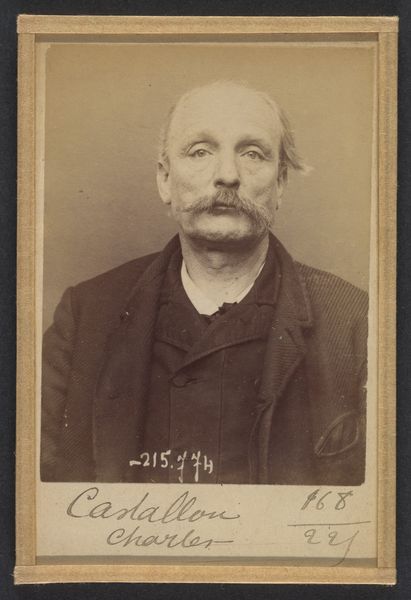

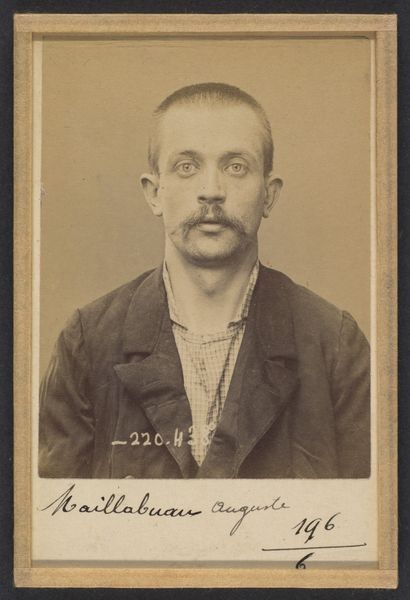

Curator: This photographic print from 1894, now held at the Met, is titled "Notelez, Charles, Emile. 29 ans, né à Paris XXe. Portefeuilliste. Anarchiste. 26/2/94." It was created by Alphonse Bertillon. Editor: He looks... resigned. The sepia tones certainly add to the solemn feel, but there's also a clarity, an almost brutal honesty in the unflinching gaze and formal composition. The man is neatly dressed but clearly under duress of some kind. Curator: Bertillon was a French police officer and biometrics researcher who applied his scientific methods to the documentation of criminals. This piece forms part of that chilling body of work. Think of this image in its original context—it’s part of a much larger file, a system designed to control and monitor individuals. Editor: And there is a sort of craft to it—an intent on recording visual information, the even lighting, the handwritten inscription and serial numbers right there on the photo itself—the work that went into archiving him into a system that strips him of his humanity but at the same time immortalizes his resistance against that act, through photography’s chemical reactions, his act of posing for the photo, his mustache. Curator: Exactly, it’s the paradox of state control. It attempts to categorize and suppress dissent, yet in doing so, it acknowledges its existence. The annotation of his anarchist affiliation, next to his profession "Portefeuilliste," or portfolio manager, speaks volumes. An anarchist working in finance. The irony isn’t lost on Bertillon and this institution. Editor: I think seeing the work outside its intended archival storage helps to refocus that irony. This photo wasn’t made to be observed by a general public. Looking at it outside that intended role allows you to almost reach out and touch this figure of the past. The craft of taking his picture turns the archive into something alive, giving breath to a revolutionary long silenced by incarceration and death. Curator: By placing these images in the public domain—here in a museum—we can engage in critical reflection and interrogate these complex systems of power. Editor: It becomes less about Notelez the criminal and more about the industrial and bureaucratic systems designed to contain people like him. What survives is the making, its intent, and unintended meaning.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.