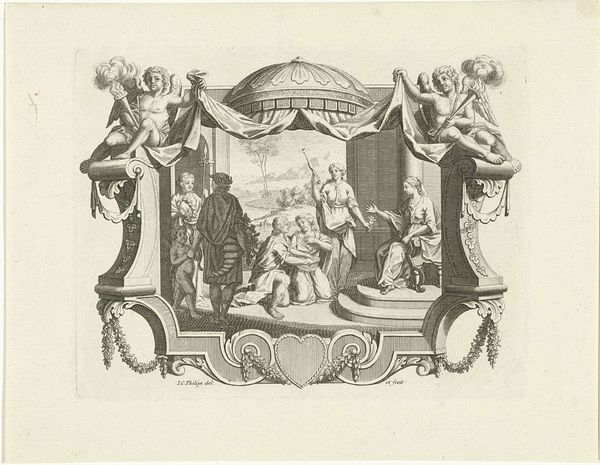

Allegorische voorstelling ter gelegenheid van het huwelijk van Willem Philips Kops en Johanna de Vos 1720

0:00

0:00

bernardpicart

Rijksmuseum

print, etching, engraving

#

allegory

#

baroque

# print

#

etching

#

etching

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 120 mm, width 144 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This print, titled "Allegorical Representation on the Occasion of the Marriage of Willem Philips Kops and Johanna de Vos," was created by Bernard Picart around 1720. It's an etching and engraving, currently residing at the Rijksmuseum. It strikes me as incredibly detailed, with so much symbolism crammed into a relatively small space. What do you see in this piece? Curator: Well, the first thing that stands out is the overt use of allegory, so typical of the Baroque era. It’s not simply a portrait of a wedding, it’s an idealized representation of marriage meant for public consumption, meant to instruct and perhaps even to legitimize. We see symbols of prosperity and fertility - note the floral abundance – intertwined with what seems like imagery associated with family life. It was commissioned to serve a particular social purpose; it acts almost like propaganda reinforcing specific ideals. How do you read the allegorical figures themselves? Editor: I think there are some figures representing virtues perhaps, and there’s Cupid aiming his arrow above. They are creating a kind of idyllic space. Curator: Precisely. The question then becomes: what socio-political statement is being made through this idealized depiction of marriage? Consider the wealth suggested by the objects, perhaps connected to this family, compared to the lives of ordinary citizens in the Dutch Republic at the time. What are we being told, implicitly, about the family’s status, their contribution to society? The commission of a piece like this solidifies their legacy and weaves them into a broader narrative. What about the display setting influences our interpretation? Editor: That’s fascinating. The way it’s framed does almost feel like a declaration. It also helps me think about why the Rijksmuseum acquired it. Not just for art’s sake, but for the insight it gives into societal values then. Curator: Exactly. The etching, now residing in a museum, transforms into a powerful tool for understanding 18th-century Dutch social and cultural norms. We now view the piece with that added context. Editor: I hadn't considered it as a sort of visual propaganda before. Seeing how social forces are at play really shifts the perspective. Curator: Absolutely. Art isn't created in a vacuum. Thinking of museums themselves as active players, framing artwork for viewers, is critical to evaluating any piece.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.