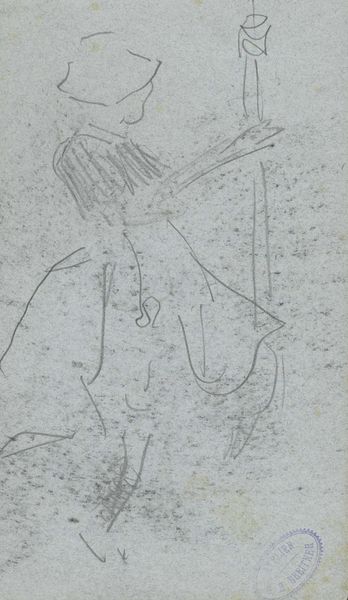

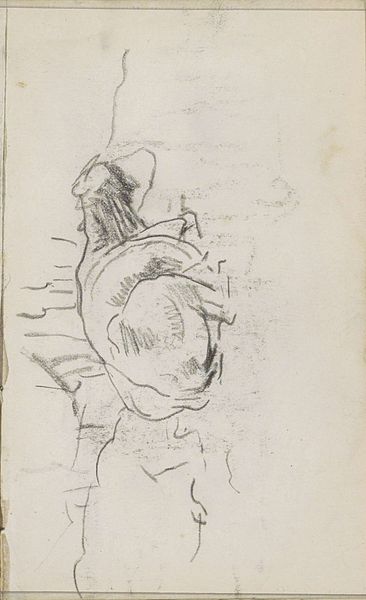

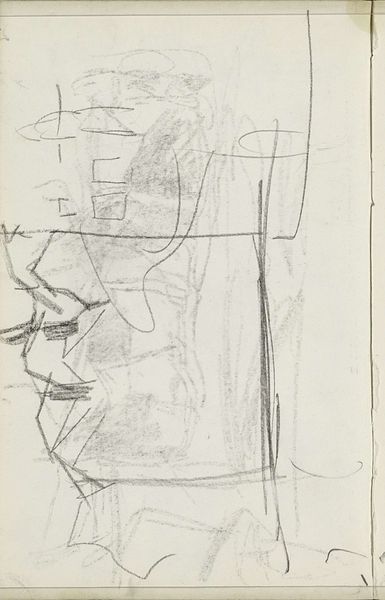

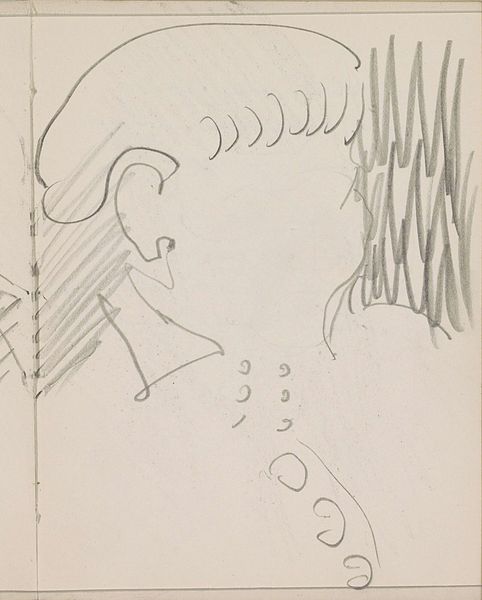

Figuur met een puntige neus en lange wimpers in profiel naar rechts Possibly 1943

0:00

0:00

samueljessurundemesquita

Rijksmuseum

drawing, paper, ink

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

comic strip sketch

#

pen sketch

#

figuration

#

paper

#

ink line art

#

personal sketchbook

#

linework heavy

#

ink

#

ink drawing experimentation

#

pen-ink sketch

#

pen work

#

sketchbook drawing

#

modernism

#

initial sketch

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

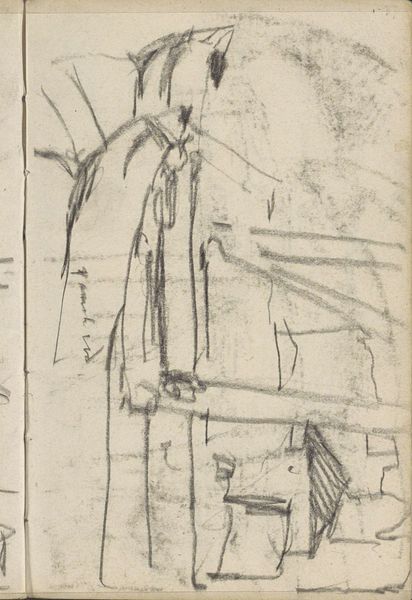

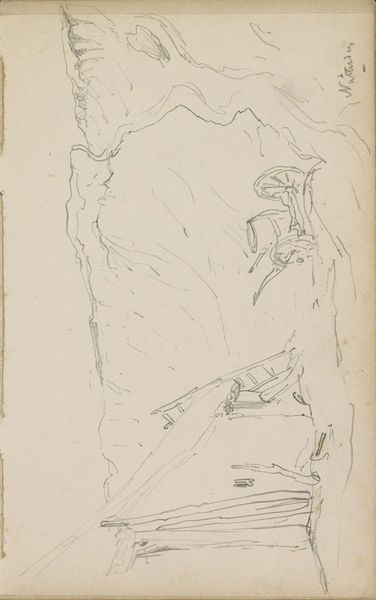

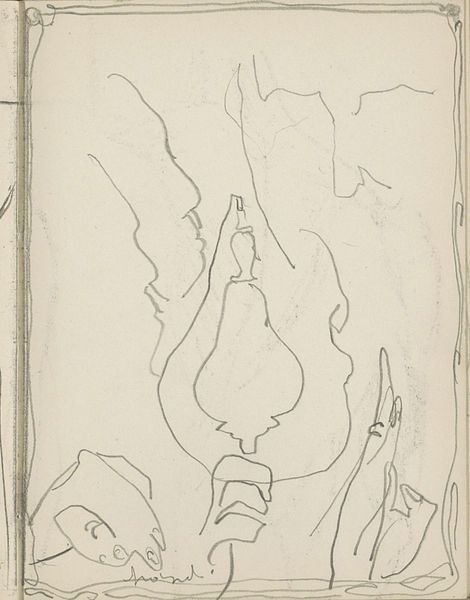

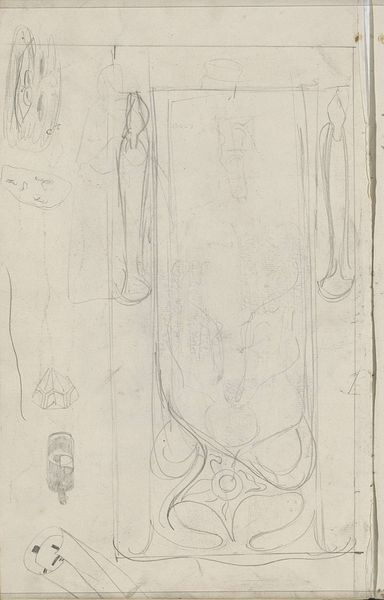

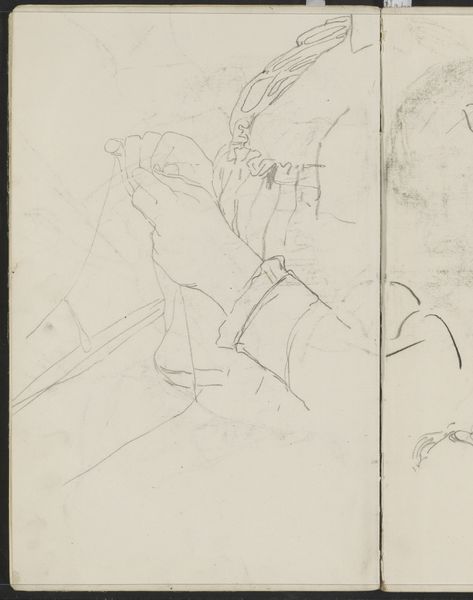

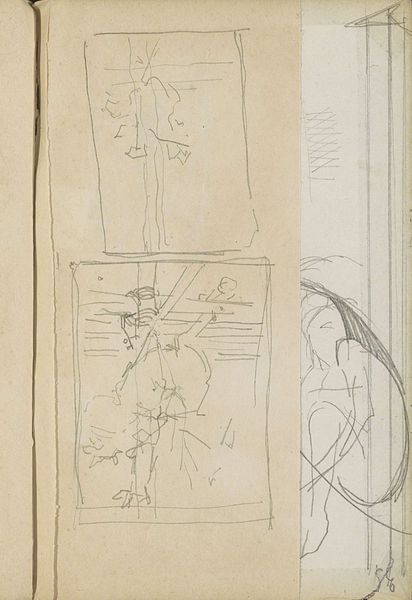

Curator: Well, here's something intriguing. This ink drawing, tentatively dated to 1943, is titled "Figuur met een puntige neus en lange wimpers in profiel naar rechts" or "Figure with a pointy nose and long eyelashes in profile to the right" by Samuel Jessurun de Mesquita. It’s held here at the Rijksmuseum. What’s your immediate read on it? Editor: Claustrophobic. The heavy linework and odd angles make me uneasy, like peering into a fractured reality crafted from stark pen strokes and cross hatching. There’s very little sense of freedom within the image’s frame. Curator: Yes, the angular forms certainly create a sense of unease. The orientation shifts destabilize the gaze. Note the way de Mesquita uses line weight to create depth and shadow. How would you assess his manipulation of the materials? Editor: Given what was happening in 1943, the limitations might reveal a more somber truth: material scarcity impacting the possibilities open to the maker, as this might be merely the scrap of paper that happened to be at hand. Pen and ink would have provided accessibility without requiring studio space or elaborate equipment. Perhaps we are seeing here a radical confrontation of confinement in its time through the immediate gestures afforded by the medium. Curator: That is certainly one reading. Consider, however, the stylized profile itself. Its exaggerated features—the sharp nose, the exaggerated lashes—along with the expressive screaming head that mirrors it diagonally above, suggesting a psychological drama playing out on paper, each of those figures are reflecting the internal experience. Editor: Agreed, but the drama also springs from the artist’s handling of line. Note how the hatching mimics textures of stone, wood and fabric. These varying textures imply process and labor and how figures become trapped within their architecture. How much can an artist really control materials, production or the impact of either? Curator: The drawing's power certainly lies in its interplay of form and emotion, regardless of intention. There is also the open book. Given his training in architecture, I am inclined to read this as an architectural rendering, an intimate design project, as much as a portrayal of figures. Editor: And for me, I keep returning to its status as something sketched rapidly from a lived situation where readily available supplies became a creative means and also potential reminders of scarcity. Curator: In either case, it offers a poignant reminder of how an artist can, even with seemingly simple materials, create complex emotional resonance. Editor: Absolutely. De Mesquita reveals just how much pen, paper and intent can transmit with such urgency and economy.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.