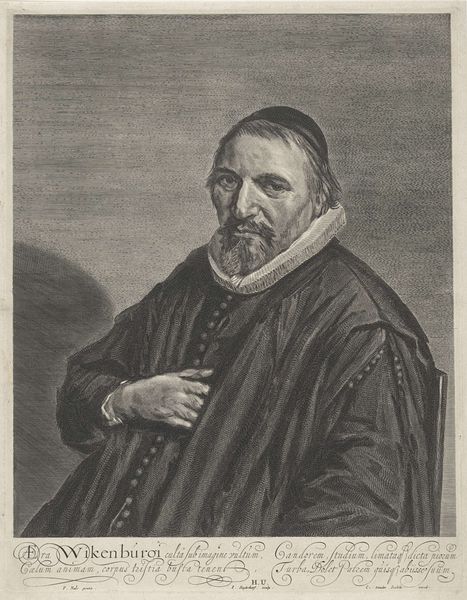

engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

#

genre-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 415 mm, width 310 mm

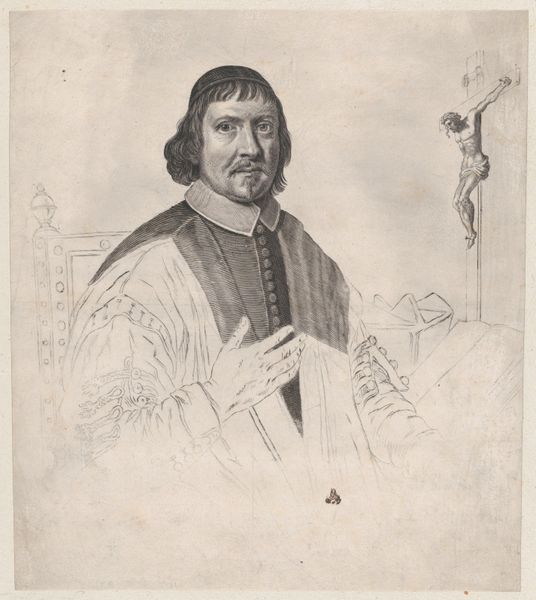

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

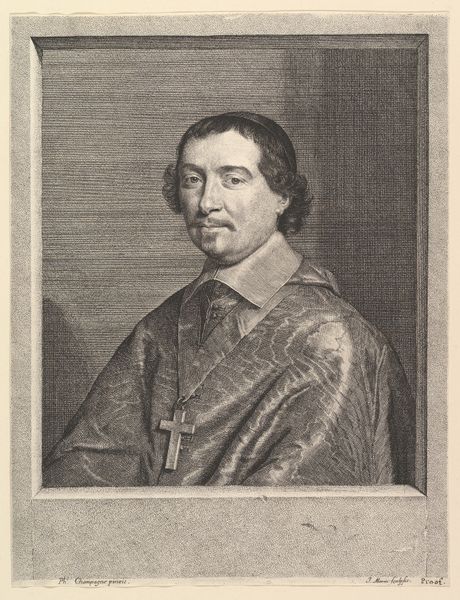

Editor: Here we have "Portret van Bernard Hoogewerf," dating from 1653-1676 by Theodor Matham, an engraving. It has this really formal, almost somber mood. I'm intrigued by how much detail Matham achieved using just lines. What stands out to you in this piece? Curator: For me, it’s the story the material tells. It's an engraving, so the labor involved is crucial. Think about the artisan carefully cutting those lines into the metal plate, mirroring the slow accumulation of knowledge and piety suggested by the portrait. Editor: The amount of labour required for that is mind-blowing. I never considered that before. Curator: Right? It becomes almost devotional itself. Notice how the lines not only define form but also seem to create textures and depth, almost simulating fabrics. The act of making echoes the values being portrayed. Do you think Matham chose engraving to add another dimension of meaning to the sitter? Editor: It could be, especially considering who the sitter was. The details in the robe suggest something costly, as is that crucifixion there... Would engravings make portraiture more widely accessible to consumers, thereby shaping and cementing ideas about the social and religious roles and values, making him somehow relatable to his public? Curator: Precisely! These reproducible images distributed power, forming visual connections across social strata, influencing societal behaviours in an age with more limited ways to document the likeness. Editor: This portrait isn't just about representation; it’s a product, a statement of skill, labour, and maybe even status due to its widespread visibility. Thanks for making me look at it this way! Curator: My pleasure! It’s about recognizing art is more than surface; it is deeply rooted in social processes, reflecting and shaping them.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.