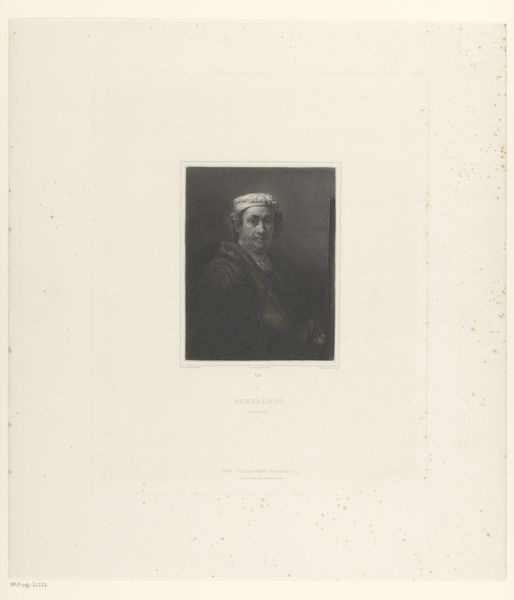

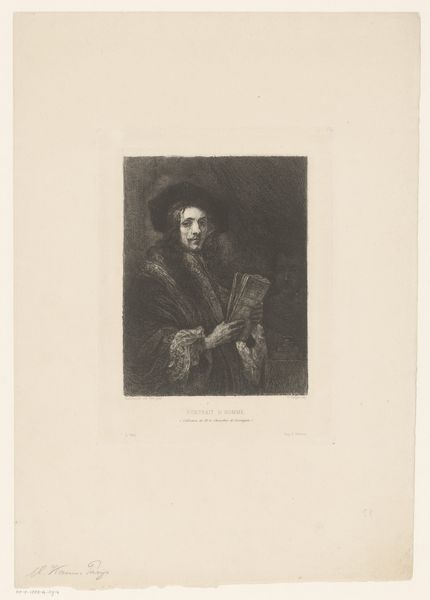

etching

#

portrait

#

etching

#

romanticism

#

history-painting

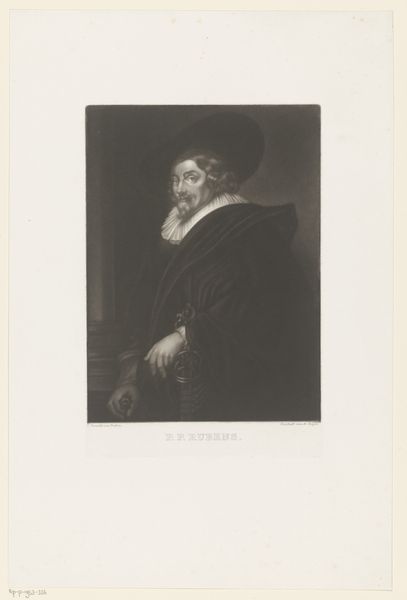

Dimensions: height 195 mm, width 154 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have Henry Edward Dawe's "Portrait of Rembrandt van Rijn," an etching from 1834. It falls squarely into the Romanticism movement, which is something we might delve into here. Editor: My first thought is, what a haunted visage! The shadows feel heavy, and there’s a real intensity in his gaze. The material, the etching, gives a softness to the historical moment too, right? Curator: Absolutely. Considering Dawe's etching comes several centuries after Rembrandt lived, we're not simply seeing a face. We're engaging with a construction, a historical interpretation, one shaped by the 19th century's fascination with artistic genius and self-portraiture. It raises the question: how do we consume historical figures? Editor: I’m wondering about access here. Etchings made art available to a public that painting couldn't reach, a very different consumer. And how did Rembrandt function, conceptually, in Victorian society, say? What role does 'great man' discourse play? Curator: Right. Dawe isn't just reproducing an image; he is also actively shaping Rembrandt’s legacy for a burgeoning middle class who could consume art through prints and who were interested in the Dutch Golden Age. How does an etching like this, available at a relatively low cost, perpetuate or challenge notions of artistic exceptionalism and access to art? Editor: Dawe isn't just passively 'copying' but adding layers of his own cultural lens to this established canon of art history, making Rembrandt a consumable item within specific social power structures. How would the audience perceive art-making and the role of art in reflecting and shaping identity during this era? The very fact that a historical figure could be revisited in a very different epoch to address socio-political issues is critical. Curator: Precisely. It demonstrates the active role art plays in shaping collective memory. This piece reveals just as much, or perhaps more, about 19th century cultural values than it does about the 17th century subject himself. It reminds us to always consider whose stories are told, how, and why, through the lens of both creator and consumer. Editor: Indeed. It invites us to critically assess not just the image, but also the socio-political narratives it perpetuates and participates in across historical periods.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.