Copyright: Public domain

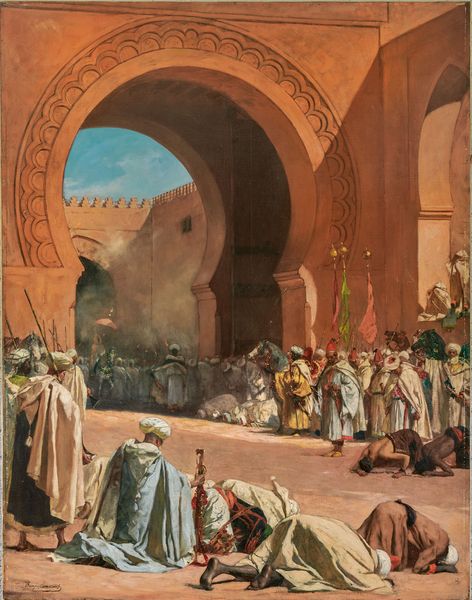

Curator: Standing before us is Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps's 1853 painting, "The Good Samaritan," currently housed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It's an oil painting depicting, as the title suggests, a scene from the well-known biblical parable. Editor: My first impression is that the muted palette gives it a somber, almost timeless quality. It feels less like a direct depiction and more like a hazy recollection of a story passed down through generations. The architecture is also striking, it doesn't resemble the middle east setting that I had in mind. Curator: Decamps, known for his orientalist leanings, sets the narrative within what appears to be a somewhat imagined or perhaps romanticized Middle Eastern cityscape. This wasn't unusual; there was a significant market in Europe for such interpretations. These artworks often reflect contemporary European perceptions and sometimes biases regarding the East. Editor: That's a crucial point. So the figures aren't simply representing the story; they are, in a sense, costumed within a visual language meant to evoke that "orientalist" feeling for a European audience. Notice the almost theatrical placement of the figures: the onlookers positioned high, as if in a box seat; the Samaritan’s compassion displayed as public act. There are two dogs resting next to the white horse, in contraposition with this biblical act of charity. Do the dogs embody skepticism towards that act, the moral conflict implied by their positions on the stone? Curator: It's certainly possible to see it that way. The choice to render them so prominently invites such speculation. Decamps likely aimed to offer more than just a straightforward illustration of the parable, it’s important to understand that these paintings entered the salons, shaping the conversations around social responsibility and Europe's place in the world, how such art was interpreted and incorporated into existing political discourse is worth attention. Editor: The turbaned figures looming from above add to this narrative a feeling of moral judgement by outside parties. I notice, too, that their figures and gestures don’t inspire any warmth, quite in the opposite. So "The Good Samaritan," becomes, more than the visual expression of the bible passage, an invitation for each individual to choose a side when faced with such injustice. Curator: I agree. "The Good Samaritan," presented within its specific historical and cultural frame, encourages deeper reflection. The work speaks both to artistic trends and to broader dialogues about responsibility, representation, and interpretation that remain relevant even now. Editor: Ultimately, it asks us, as viewers both then and now, to consider not just the act of kindness, but how we are implicated as onlookers within these ever-unfolding narratives of humanity and empathy, challenging us to see with eyes unclouded by prejudice and social conventions.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.