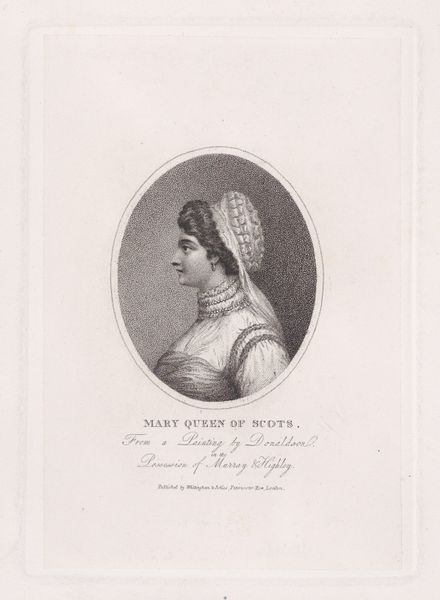

drawing, print, intaglio, paper, engraving

portrait

drawing

neoclassicism

intaglio

paper

england

men

history-painting

engraving

Dimensions: Sheet: 6 5/16 × 3 7/8 in. (16.1 × 9.8 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: Here we have William Ridley’s 1799 engraving, “Mary, Queen of Scots,” currently housed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It strikes me as quite somber, almost stoic, especially given what I know about her…difficult life. What do you make of it? Curator: Somber indeed. I see echoes of her tragic story, yes, but also a strength in her gaze. It's an interesting dance Ridley does, capturing both vulnerability and resolve. Notice the Neoclassical style, very much en vogue, almost deliberately downplaying drama in favour of cool composure. Do you think this distancing actually enhances the pathos, paradoxically? Editor: Hmm, I hadn't thought about it that way! The restrained style almost amplifies the sadness. Is there something to be read in the decision to use printmaking? Curator: Absolutely! Prints, especially engravings, were accessible. This wasn't a royal commission destined for a palace wall. This was meant for a wider audience, to circulate and shape public perception of a historical figure—even stoke sympathy. Think of it as early PR, with a somber spin. What details really pull you in? Editor: I am struck by her elaborate headdress… It really locks her into that time period, makes her feel far away, yet strangely familiar given the volume of film and literature on her life. Curator: It's fascinating, isn’t it, how material culture – that lace, those pearls - acts as both a bridge and a barrier to the past? This image makes her story linger and challenges the viewer to reconsider assumptions. Editor: I’ll certainly think differently about how portraits were presented back then, not only for royalty. Curator: It's like looking through a window, darkly.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.