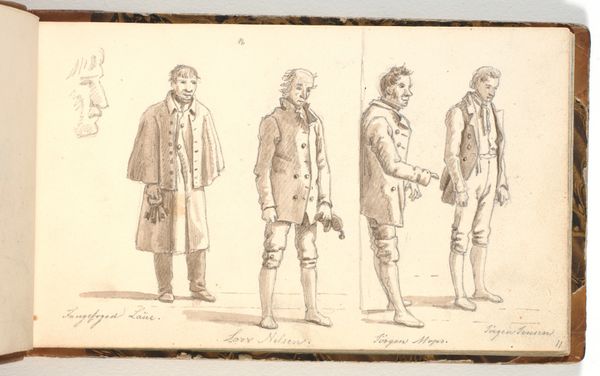

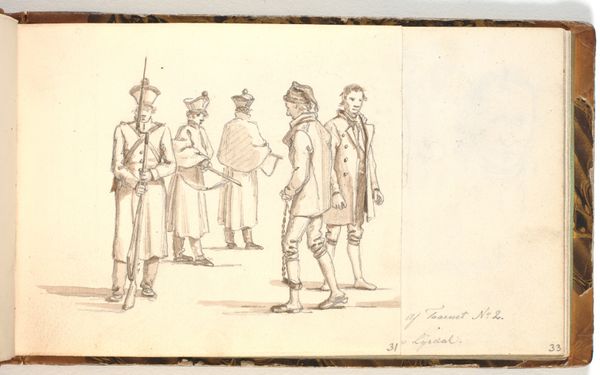

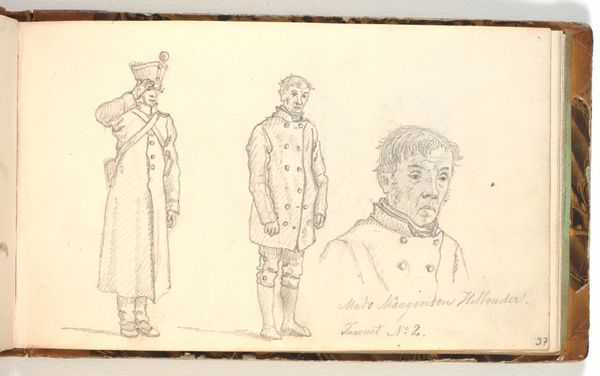

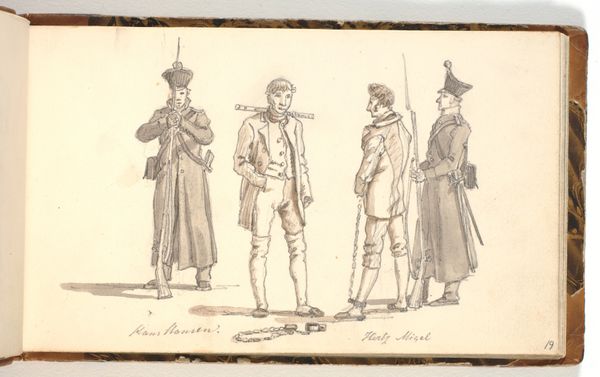

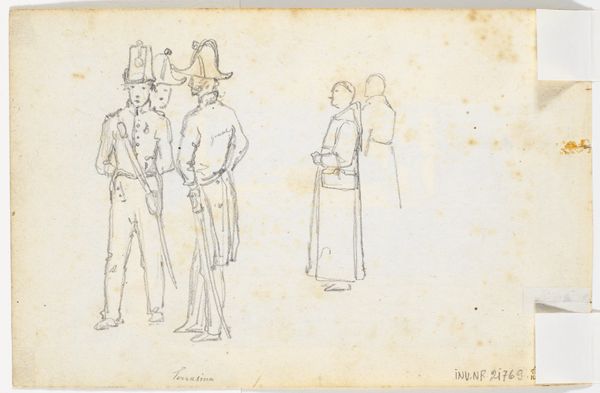

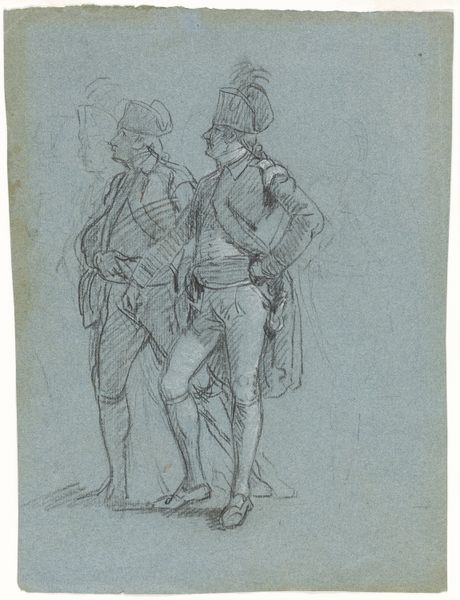

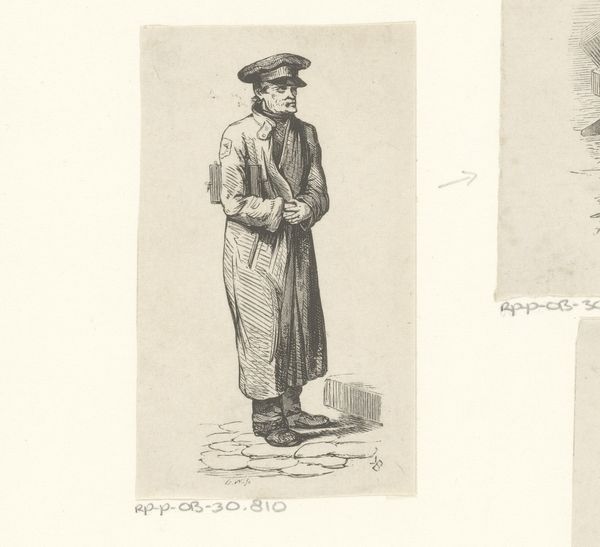

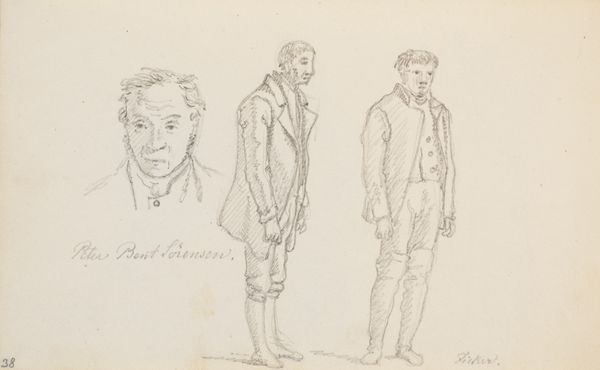

drawing, pencil, pen

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

romanticism

#

pencil

#

pen

#

genre-painting

#

academic-art

Dimensions: 105 mm (height) x 176 mm (width) (bladmaal)

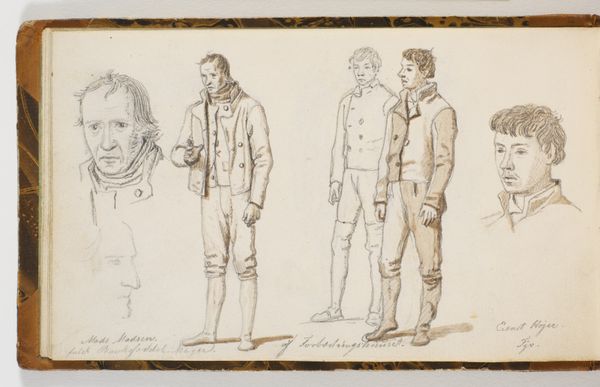

Curator: Rørbye's 1832 work, "Three Studies of Prisoners from the Improvement House," strikes me as unsettling yet delicately rendered. There's something immediately captivating in its understated quality. Editor: Unsettling is right. It's the quiet expressions on their faces, coupled with their somewhat absurd garb, that creates such tension. It’s both comical and tragic at once. Curator: It's interesting to see this almost objective, ethnographic-like depiction of these prisoners during a period of significant social reform in Denmark. The "Improvement House" itself represents an evolving approach to incarceration—moving from purely punitive to rehabilitation. Editor: And yet, chains remain, a visual reminder of constraint and the societal mechanisms that brand these individuals. The slight variations in their posture and the details like the manacled feet highlight their individuality, resisting a purely dehumanizing representation. You see echoes of phrenology and other dubious sciences in the attempt to categorise individuals, a common thread in nineteenth-century Europe, but it's countered with a quiet observation. Curator: Exactly. Rørbye's background is academic. So, the meticulous, almost clinical observation is not surprising. He was trained to depict reality accurately. Editor: But is it truly accurate? I wonder to what extent Rørbye's perspective and the societal prejudices of the time colored his representation of these men. His depiction, while technically skilled, perhaps tells us more about societal anxieties and reformist zeal than about the actual lived experiences of the prisoners. Curator: I see your point, but perhaps its power lies in this tension. Rørbye wasn't overtly judgmental. He offers a glimpse into a particular historical moment, capturing its contradictions. Editor: It prompts me to think critically about our carceral systems today. In what ways are we simply repackaging old prejudices and justifications for controlling marginalized populations? It highlights that punishment and "rehabilitation" can, at times, mask deeper inequalities and power structures. Curator: Absolutely. Considering all this, I think we see the power in the drawing’s unassuming appearance. Editor: It leaves us with uncomfortable questions about justice and representation. Perhaps that’s its ultimate value.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.