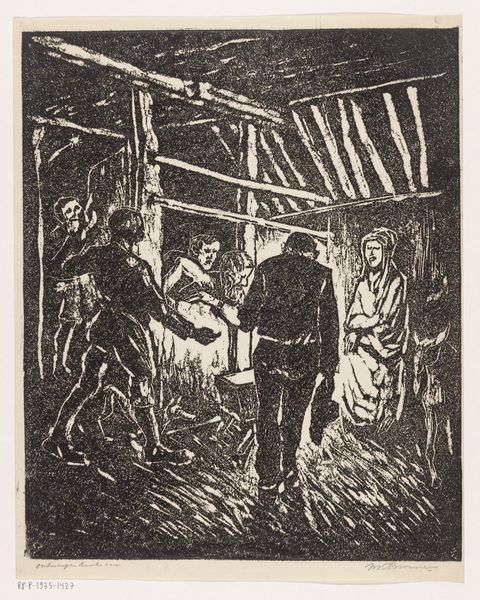

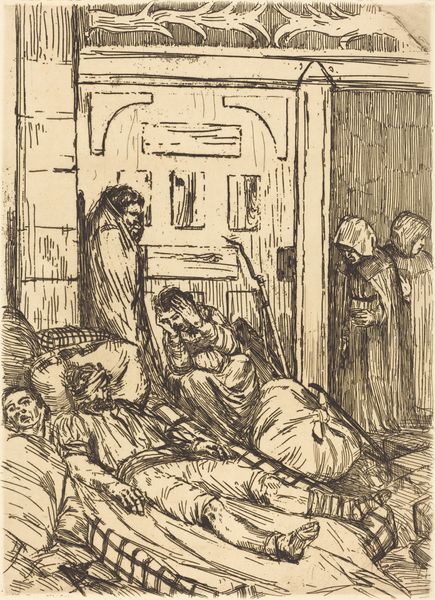

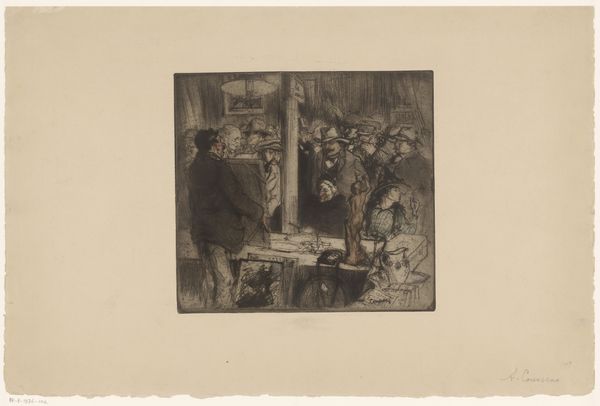

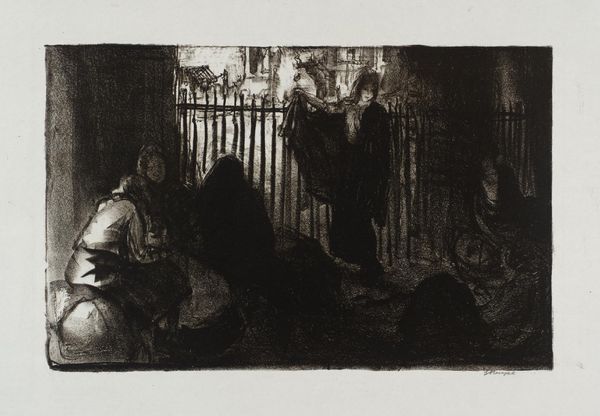

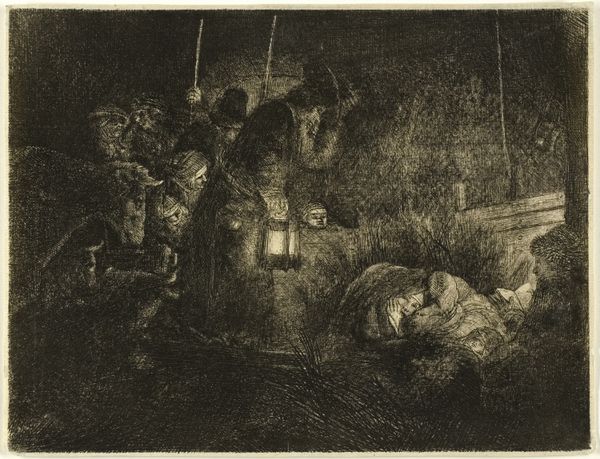

drawing, print, etching

#

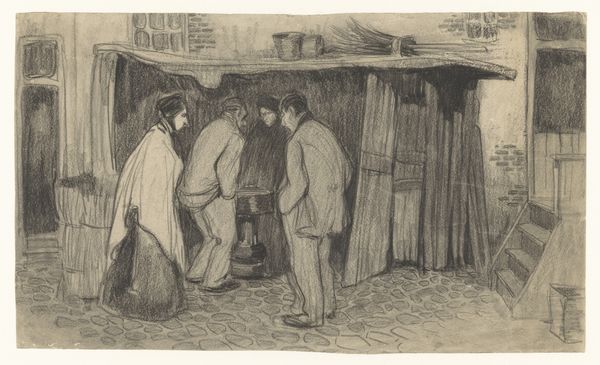

drawing

#

narrative-art

# print

#

etching

#

german-expressionism

#

figuration

#

social-realism

Dimensions: 336 mm (height) x 407 mm (width) (bladmaal), 237 mm (height) x 300 mm (width) (billedmaal)

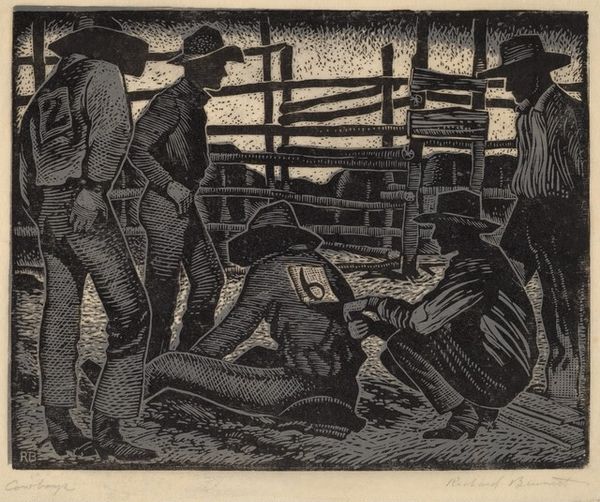

Curator: Kathe Kollwitz’s etching, "Ein Weberaufstand - Ende," or "The Weavers' Revolt - The End," created between 1897 and 1898, is a stark depiction of societal upheaval and its aftermath. The artist produced it, deeply moved by Gerhart Hauptmann’s play "The Weavers," portraying the Silesian weavers' uprising. What feelings does the imagery stir in you? Editor: A heavy sense of resignation and despair. The figures are cloaked in shadows, and the two men prostrate on the floor exude exhaustion. It feels like all hope has been thoroughly extinguished. It makes you contemplate not only the individual struggles but also the crushing weight of history. Curator: Precisely. The recurring visual motifs within Kollwitz's broader cycle around the revolt invite contemplation. Notice the contrast between the standing figures, rendered with stark, almost grotesque lines suggesting resilience. It might evoke cycles of suffering and defiance, as though it's deeply etched into the social consciousness. Editor: The figures bear a resemblance to tragic characters from classical antiquity; one standing figure, the stoic woman on the left, appears burdened by fate and sorrow. What meaning does Kollwitz imbue into the archetype of the suffering mother or widow figure? Curator: She embodies profound suffering, a timeless symbol present across epochs and cultures. Consider, too, that in German Expressionism, which Kollwitz helped pioneer, such representations were utilized to expose the raw emotional states that modernization had suppressed. The figure then stands as an emblem of both personal loss and the wider social tragedy brought on by unchecked industrial capitalism. Editor: It seems, then, that Kollwitz intentionally blurs the lines between the personal and political to make a clear statement on exploitation and inequality. What about the ways her prints, in particular, facilitated this communication? Curator: Absolutely. Kollwitz used etching and printmaking techniques not just for their stark, emotionally charged aesthetic qualities, but also for their accessibility. Prints could be circulated widely, reaching broader audiences to spark awareness of the dire conditions faced by working-class individuals. Each image then becomes a small act of political assertion. Editor: So this piece goes far beyond just illustrating a historical event. It taps into primal emotions and symbols that still resonate today, offering not only social commentary but also psychological insight into collective trauma and resilience. Curator: Yes, and I find that exploration of these shared human experiences across time—particularly those interwoven with oppression—remain remarkably vital when we bring the piece to our own contemporary sociopolitical context.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.