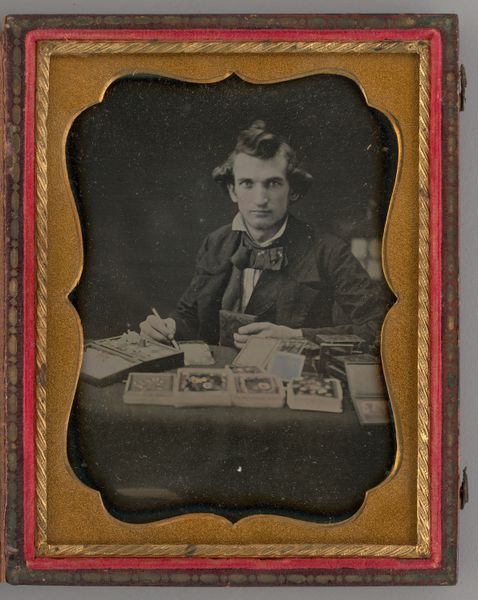

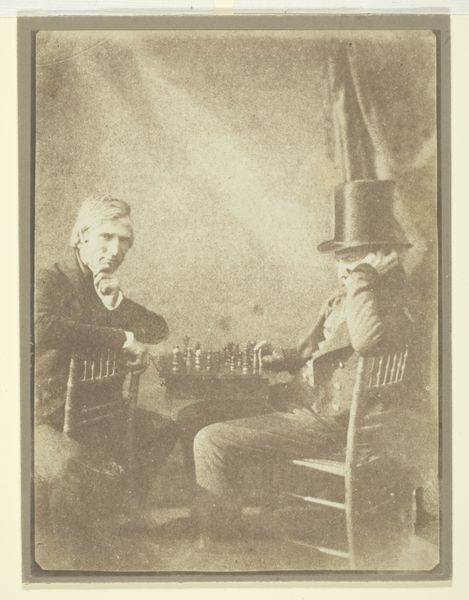

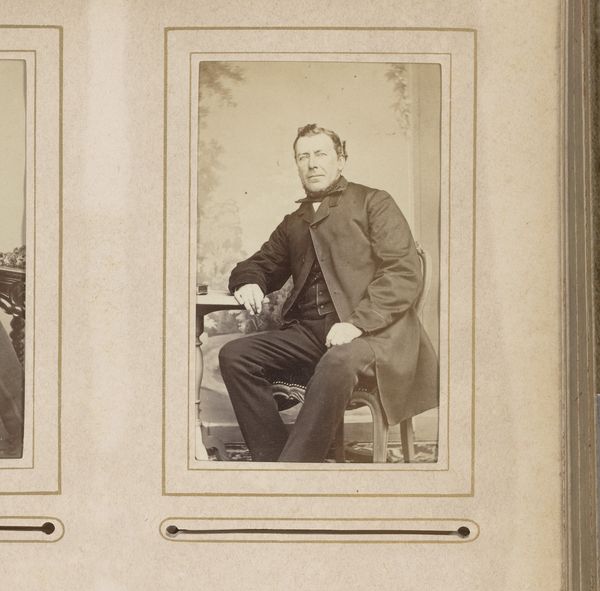

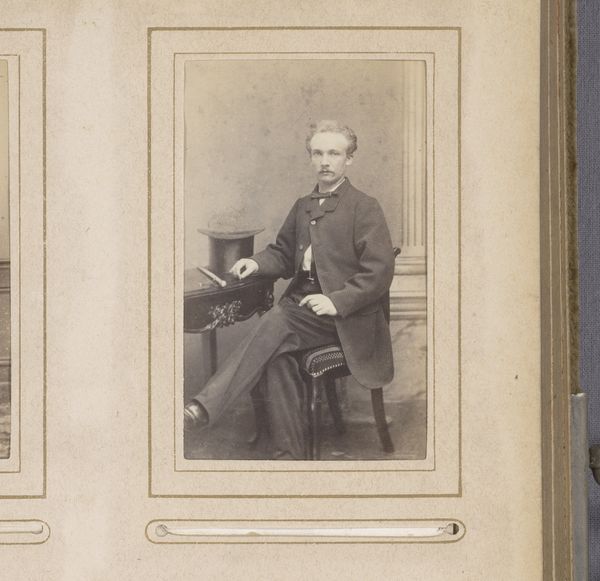

daguerreotype, photography

#

portrait

#

16_19th-century

#

daguerreotype

#

photography

#

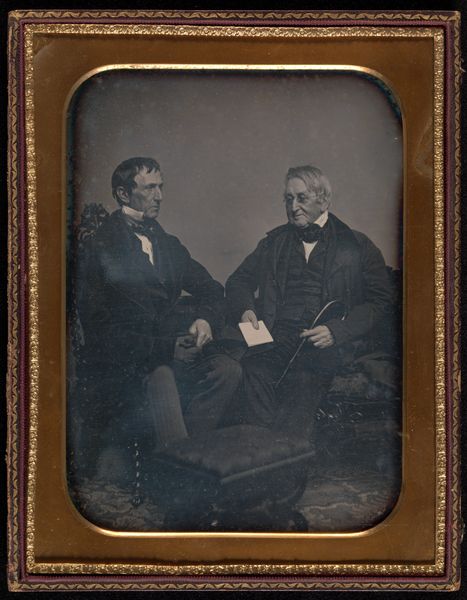

realism

Dimensions: 10.7 × 8.3 cm (4 1/4 × 3 1/4 in., plate); 12 × 19 × 0.9 cm (open case); 12 × 9.5 × 1.6 cm (case)

Copyright: Public Domain

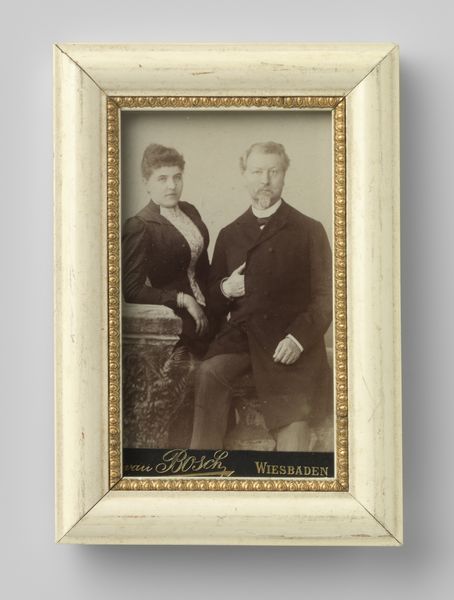

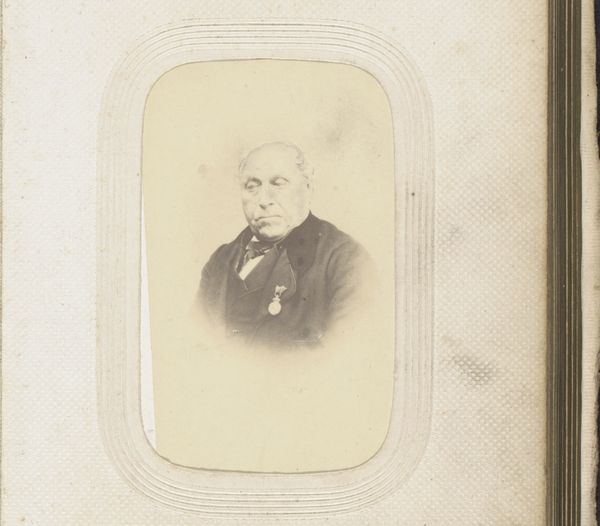

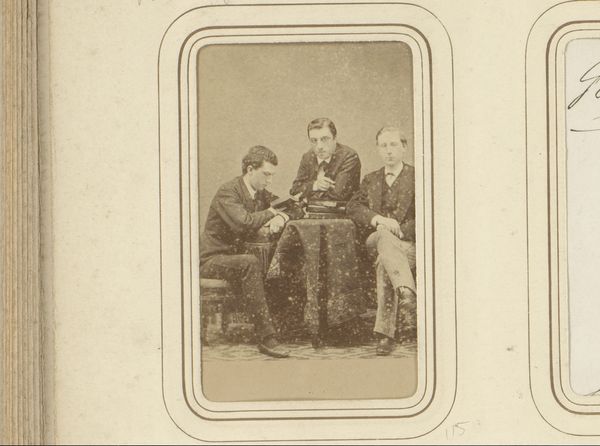

Curator: Here we have an untitled daguerreotype, circa 1857, currently residing at the Art Institute of Chicago. The work presents a portrait of two seated men. What is your first reaction? Editor: My immediate response is one of intimacy—though staged, the photograph exudes a sense of connection. Their gazes meet, and the book shared between them hints at intellectual kinship, a quiet moment captured within a turbulent historical era. Curator: Indeed. It's important to consider the historical context of daguerreotypes themselves. The development and proliferation of this medium in the mid-19th century democratized portraiture in a way previously unimaginable. Only the wealthy could afford painted portraits before this. What sort of shift in power dynamics are we observing here? Editor: The democratizing effect is crucial. Suddenly, the middle class and even some working-class individuals could access a form of visual representation that cemented their presence in history. It challenges elitist historical narratives—visual sovereignty expands, particularly for marginalized individuals who may not have had the economic capital or family status to control their visibility. But it should be stated, such expansions also reinforced existing race and class dynamics by furthering limiting how these were constructed and portrayed, such as with anti-black minstrel imagery, as the country debated the morality of slavery. Curator: I agree. And let's not forget the technical limitations. The lengthy exposure times required meant subjects needed to remain perfectly still, often resulting in these solemn expressions we see here. But how do you see that affecting the reception or intended meaning behind this particular portrait? Editor: Those constraints arguably contribute to a kind of sincerity. There's a commitment in their stillness, an investment of time and effort to present themselves intentionally. Looking at their faces, it's evident that care and thoughtfulness were placed into the presentation of each person for the camera. The shared book—what are they reading?--functions almost like a subtle, perhaps carefully constructed performance of shared respect and maybe friendship between the men. A narrative in itself. Curator: Perhaps a symbolic embrace of shared literary or intellectual interests, certainly crafted within the limitations, but ultimately, expanding access in who is worthy of representation in art. Editor: Precisely, and those expanded inclusions begin challenging social hegemonies. Curator: That is a worthy takeaway from this piece and daguerrotypes broadly, one worth pondering even after we move along. Editor: Indeed, especially when analyzing art’s power in a rapidly shifting culture and social world, as occurred in the late 1850s.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.