print, photography, gelatin-silver-print

# print

#

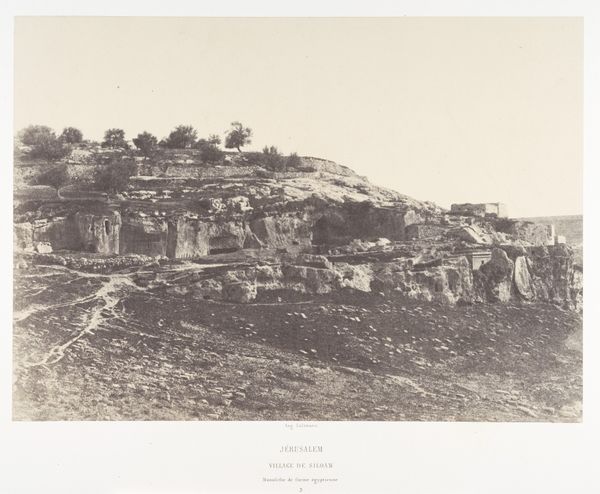

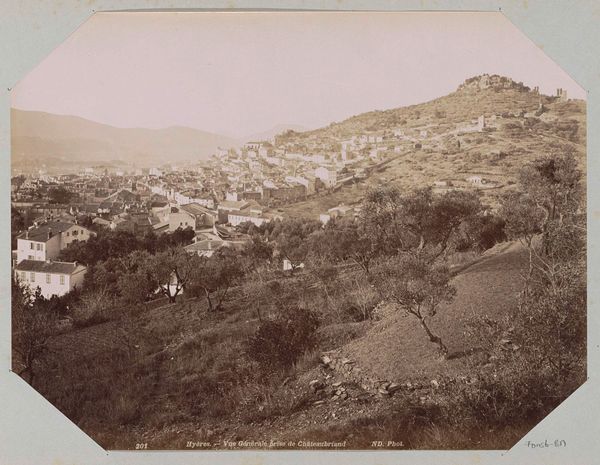

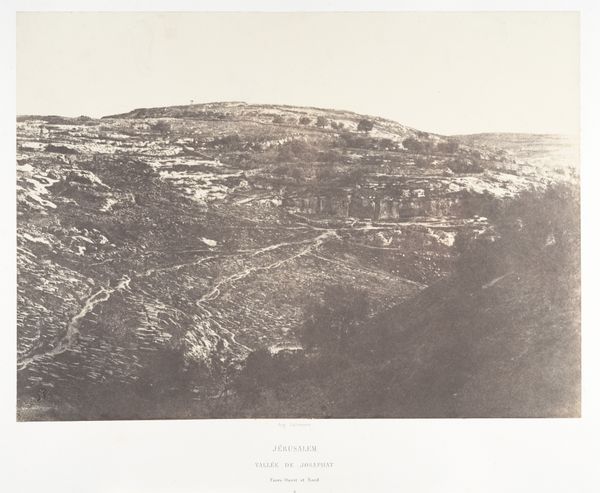

landscape

#

charcoal drawing

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

mixed medium

#

watercolor

#

realism

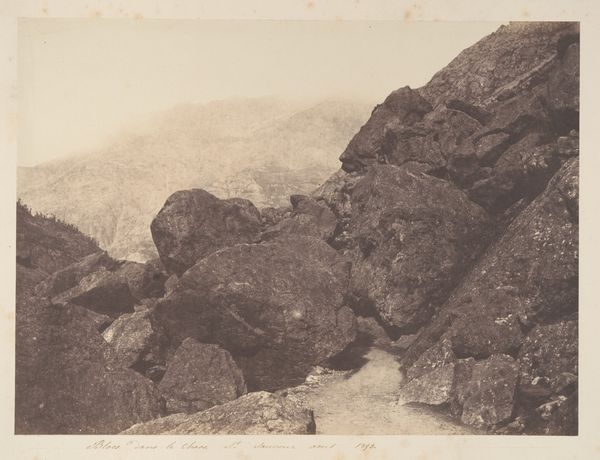

Dimensions: height 153 mm, width 205 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

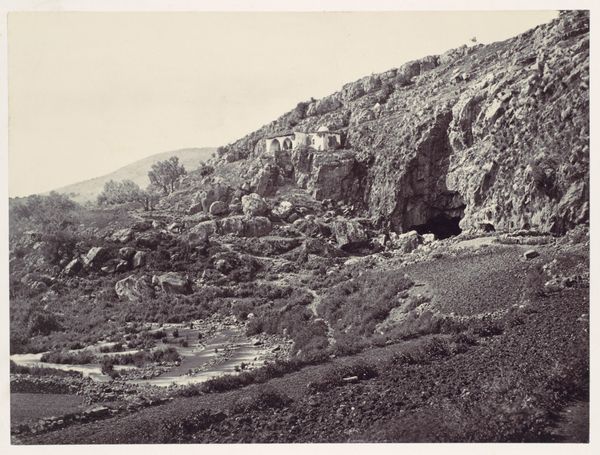

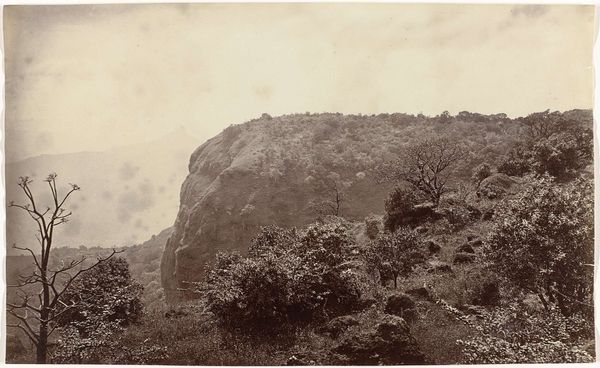

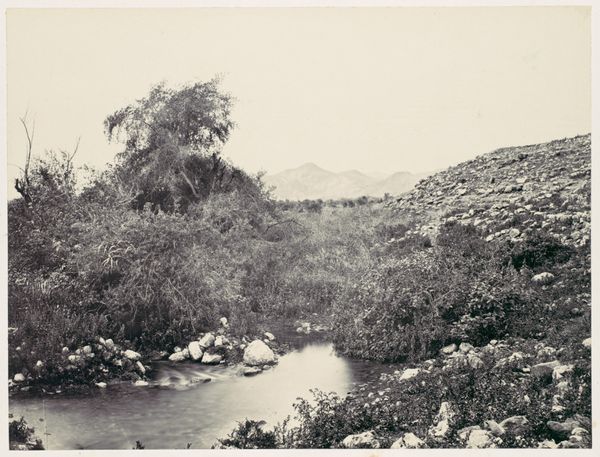

Curator: David Barnett gives us "Weg door een kloof bij Wonderboompoort", likely captured between 1890 and 1920. It’s rendered in a gelatin silver print, offering a glimpse into a landscape seemingly untouched. Editor: Stark. The composition almost suffocates you with those looming rock formations, doesn't it? The monochrome adds to the drama. Curator: Absolutely. Gelatin silver prints like this one were becoming increasingly popular at the time for their sharpness and tonal range, perfect for capturing the harsh textures of this South African landscape. You can almost feel the dryness and the intense sunlight. Considering Barnett’s profile, his access to materials for photographing landscapes like this might have been associated with early tourism or documentation efforts in South Africa. Editor: That’s fascinating. Looking at it through a social lens, the framing becomes more pointed. Who was this made for? Who was meant to consume this view of Wonderboompoort, and what did it represent to them? The single tree at the horizon feels almost like a symbolic marker—survival? Resilience? Curator: Those are excellent questions to probe. Gelatin silver prints enabled easier replication and wider distribution compared to earlier photographic processes. The "Weg door een kloof bij Wonderboompoort", captured via photographic print, could have circulated as postcards or documentary images, shaping perceptions of the region back in Europe or amongst the colonizers on site. Editor: So, we need to consider the institutions that would display such an image too: geographical societies, maybe? And the market—was this considered art or documentary evidence? Even the framing suggests a particular way of seeing and commodifying landscape. The rugged terrain seems less inviting than imposing. Curator: Precisely. And if we consider the print itself, beyond its artistic merit, we also confront the environmental conditions—the chemical processes that transformed silver and gelatin, creating this enduring artifact. It connects to mining, trade routes, colonialism—layers upon layers. Editor: It’s a somber beauty. Knowing a bit about its materials and the socio-political context, really deepens the experience, wouldn't you say? Curator: Indubitably. The photograph is more than meets the eye: it becomes a vessel of complex histories and material realities, challenging the way we look at landscapes and their artistic portrayals.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.