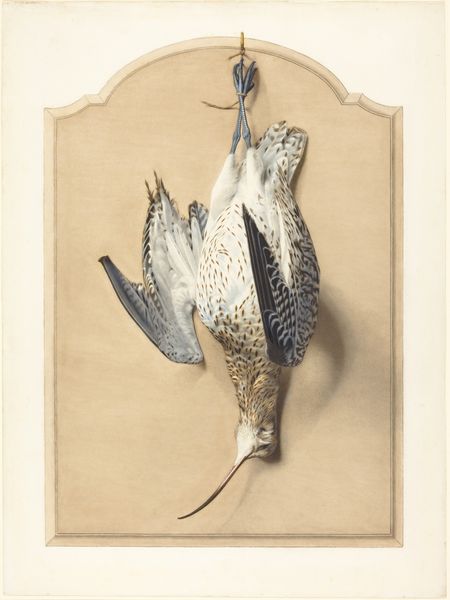

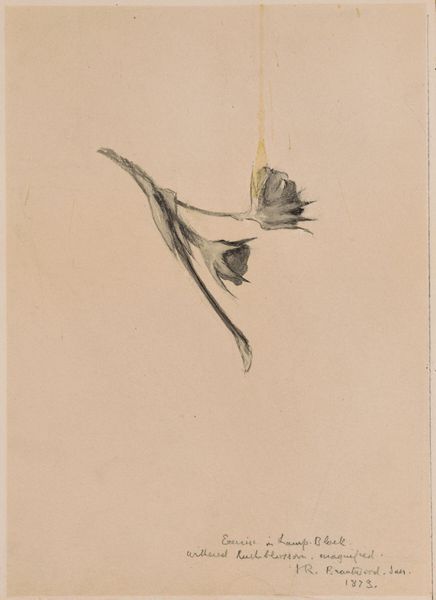

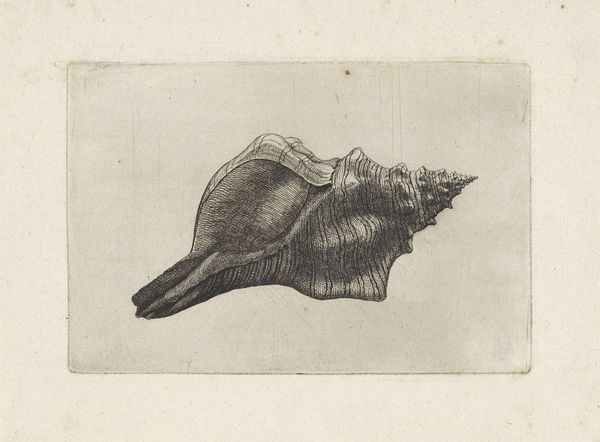

drawing, watercolor

#

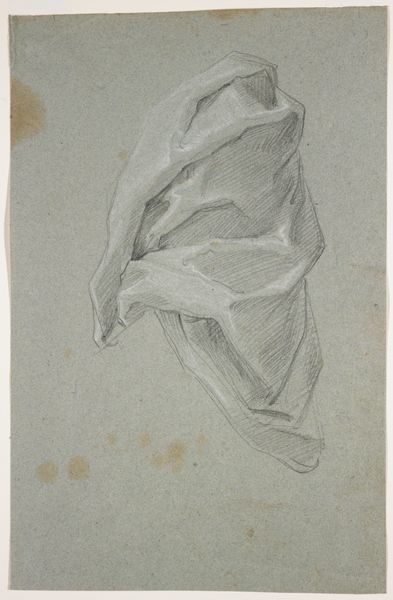

drawing

#

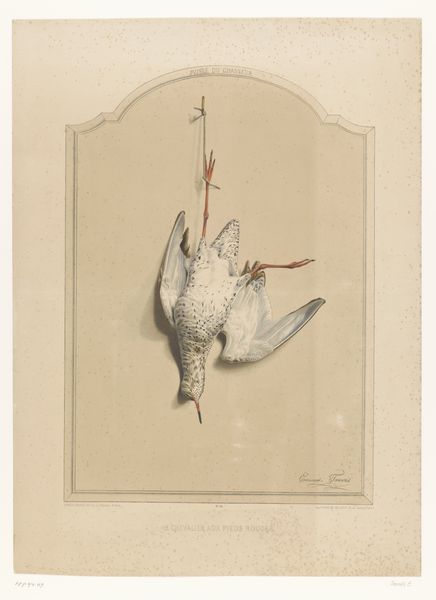

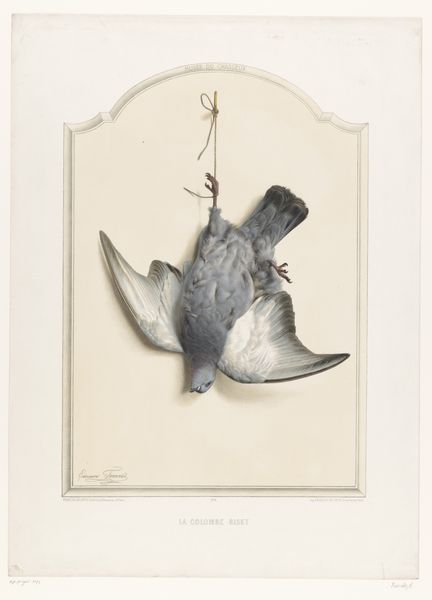

watercolor

#

ceramic

#

academic-art

#

botanical art

#

watercolor

#

realism

Dimensions: height 238 mm, width 200 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So, this is Hendrik Gerrit ten Cate’s "Scharretje," made in 1837, using drawing and watercolor. It’s a very… detailed depiction of a flatfish. It's a bit morbid, but also quite striking in its realism. How do you interpret this work? Curator: I see this piece as situated within the complex intersection of art, science, and colonialism of the 19th century. Can we really separate botanical or zoological drawings from the larger project of classifying and controlling the natural world, particularly in the context of European expansion? What does it mean to meticulously depict a single fish like this? Editor: I hadn't considered the connection to colonialism! I was mostly thinking about the still life tradition and ideas of mortality. Curator: Precisely! Think about the power dynamics at play. Who gets to decide what is worthy of being depicted, studied, and ultimately, consumed? Is it possible that this seemingly objective representation is actually reinforcing a specific worldview, a specific system of value? Editor: So, it's not just about capturing the fish's likeness, but also about asserting a certain level of control over it? Curator: Exactly. And perhaps even transforming it into a commodity, viewed primarily for its utility rather than its intrinsic value. This kind of artistic representation contributes to a culture that enables ecological exploitation. Have you noticed how its neutral background allows to center stage what Europeans consume? Editor: That’s a pretty unsettling perspective, but it makes you think about the choices artists make. Thanks for showing me this perspective, I'll certainly remember it. Curator: Likewise, you reframed my point of view on still life as simply “morbid." I found it to be insightful and refreshing.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.