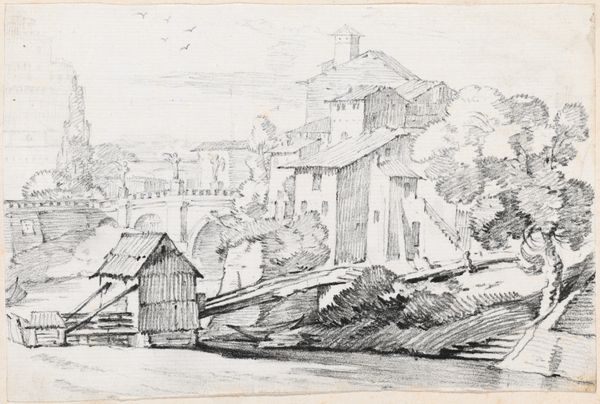

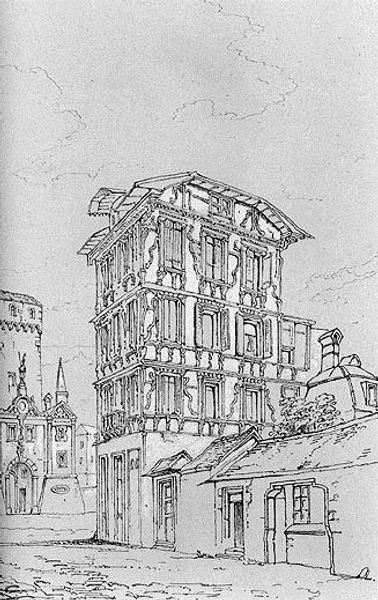

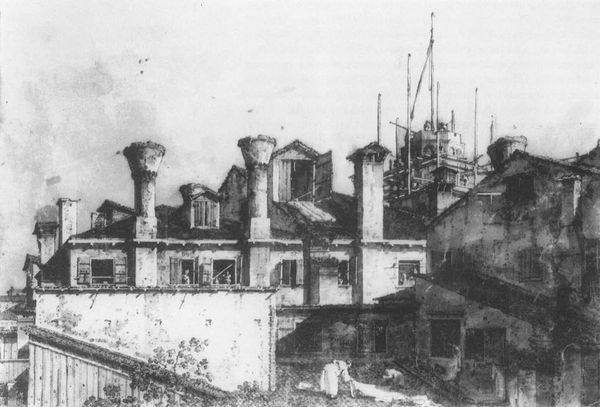

Dimensions: 339 mm (height) x 489 mm (width) (monteringsmaal), 321 mm (height) x 379 mm (width) (bladmaal)

Editor: This is “Garverierne i Falaise, Normandiet,” or “The Tanneries at Falaise, Normandy” by Othon Friesz, created between 1901 and 1904. It’s a drawing. I'm struck by the density of the buildings, especially compared to the lighter sky. What do you see in this piece? Curator: I see more than just an architectural study; I see a portrait of labor and industry embedded in the everyday. Falaise was, and to some extent still is, defined by its tanneries. Friesz is not simply representing buildings, but implicating them in the larger political economy of the region. Notice how the monochromatic palette drains any romanticism from the scene, underscoring the grit and the potentially dehumanizing aspect of industrial work. What does this tonal choice evoke for you in terms of the working class experience? Editor: That makes sense. It feels less picturesque and more…stark, almost documentary-like. Is he making a specific commentary about the conditions of the tanneries? Curator: Precisely. Impressionism is often read for its aesthetic qualities, but we need to remember these artists were also living through periods of significant social upheaval. Consider the implications of rendering such a scene as opposed to a lavish portrait of the bourgeoisie, as so much art of the period did. He forces the viewer to confront a segment of society that was often intentionally made invisible. What questions does that raise about visibility, and who controls it? Editor: So, by choosing this subject, Friesz is actively engaging in a conversation about class and labor conditions. Curator: Absolutely. And think about how Friesz frames the composition. The building dominates the foreground, almost blocking the view. This feels purposeful, making a strong, even forceful, statement about the prominence of this industry. This prominence then poses questions of responsibility for those in power. It’s not just a pretty picture of France. Editor: I didn't consider how Friesz might be using the scene itself to provoke a dialogue on industrialization and labor. That gives me a lot to think about. Curator: Indeed. Hopefully, this gives our listeners more appreciation for interpreting the subject as cultural and political criticism, and an entrypoint for discussions of the ethics of representation in art.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.