photography

#

portrait

#

print photography

#

photography

#

realism

Dimensions: height 171 mm, width 123 mm, thickness 0.09 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

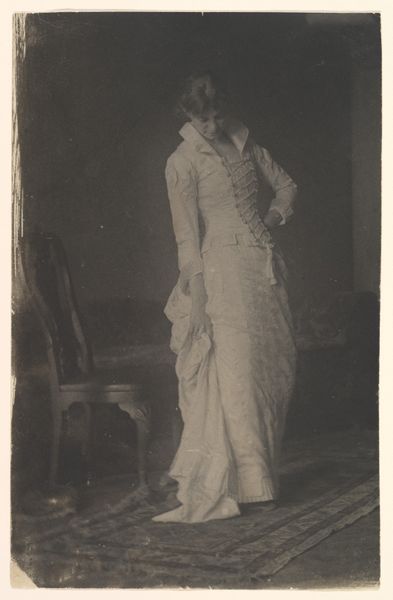

Curator: We're looking at "Portrait of an Unknown Seated Woman," a photograph taken by Charles Nègre between 1853 and 1855, currently held in the Rijksmuseum collection. Editor: It's striking, isn't it? There's an almost ethereal quality to it, like a faded memory brought to life. The woman's gaze is intense despite the softness of the print. I am immediately drawn to the tension between her hand gesture touching her face as if reflecting, versus the rigid lines of the chair. Curator: Nègre was working during a pivotal time in photography. The medium was still finding its footing as both art and documentation. Portraits like this, depicting the burgeoning middle class, challenged the existing power structures of representation. Who had the right to be remembered? Editor: The drapery behind her has such an odd energy. You can tell the artist intentionally plays into ideas of presentation, hiding, and revelation all at once. It also emphasizes the contrast between light and shadow, almost reminiscent of Renaissance paintings, the artistic memory is striking in such a recent form of representation as photography. The sitter could almost be a new Judith... but who is she? Curator: Exactly, and it begs the question of the gaze. She's looking just off to the side, not engaging the viewer directly. Is she trapped by the confines of the studio, reflecting the limited social roles available to women at the time? Editor: Or perhaps she is an oracle, sitting for her depiction, inviting us into her psychic world. It is curious that Nègre choose not to give the artwork a specific title other than “seated woman.” It feels intentional, especially given the symbolism often attached to women sitting for portraits: stillness, subservience, expectation, but the way she gazes beyond those expectations speaks to another intention, of expectation itself as her tool. Curator: These are photographs produced relatively early in its history, before photojournalism or even street photography were normalized and popular. You start to understand how women’s posture could be considered confrontational if not perfectly accommodating and subservient in public portraiture like this one. Editor: It all points to the inherent symbolism in this image. Whether we see subjugation or veiled power, Nègre has captured a moment thick with unspoken narratives, a visual testament to a woman we'll never know, yet feel we recognize on some archetypal level. Curator: Absolutely, this piece is far more than just an early photographic print; it serves as an interesting entry point into understanding gender roles and power structures in the 19th century.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.