Dimensions: height 108 mm, width 167 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

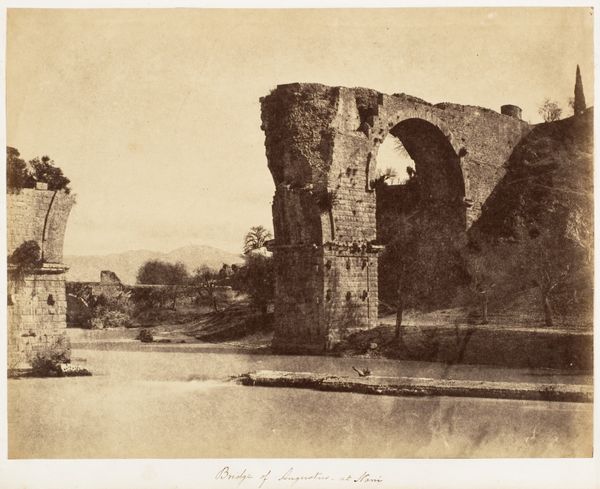

Curator: Pieter Oosterhuis created this compelling gelatin-silver print, titled "Ruïne van Brederode, Santpoort-Zuid," sometime between 1867 and 1883. Editor: It's remarkably textured. Look at how the light catches on the ruined stone – you can almost feel the roughness. It evokes a strong sense of melancholy, wouldn’t you agree? Curator: Absolutely. Ruins in this period were often photographed, feeding into a broader Romantic fascination with the past. There's a certain picturesque quality, framing nature reclaiming what was once a man-made structure of considerable importance, both politically and symbolically. Editor: The ruin becomes a monument to the passing of time and the fragility of power structures, visibly illustrating history and its impact on building materials and structural techniques over time. Was this accessible to everyone, the site itself? Curator: Initially, yes, and I think Oosterhuis deliberately played into the increasing accessibility of art and culture. Photography itself democratized image-making and viewership, and these ruined structures acted as places to physically view Dutch history on display. Editor: And even the making of the image points to something wider, doesn’t it? Silver gelatin was far more economical than some previous photographic methods – easier to get hold of, wider production, and perhaps part of the impulse of a more bourgeois vision of art itself. Curator: I concur; the method enhanced photography's status in popular culture. Images became objects of both public and personal importance. We see this, for instance, with how widely photos were incorporated into early forms of tourism—photos used almost as keepsakes. Editor: And look how photography's ability to replicate the detail also elevates ordinary materials and sites into monuments—as we are stood doing right now. The ruin would have become just as familiar as the photo; it reminds us that these processes, in photography but also in the labor required to build ruins in the first place, were accessible as an element of civic society. Curator: True, what the subject and medium make clear is that by viewing such objects we become active participants within it. That photograph in a person's home becomes a way of displaying allegiance to certain ideas about Dutch history. Editor: It makes you reconsider what labor goes into both erecting such monuments to power and creating such detailed visual records that can spread throughout the region, reinforcing a visual landscape. It certainly is haunting, the picture. Curator: A powerful study, particularly when viewed within the socio-political forces present at the time of its making.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.