painting, oil-paint

#

gouache

#

narrative-art

#

painting

#

oil-paint

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

oil painting

#

romanticism

#

watercolour illustration

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

watercolor

Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

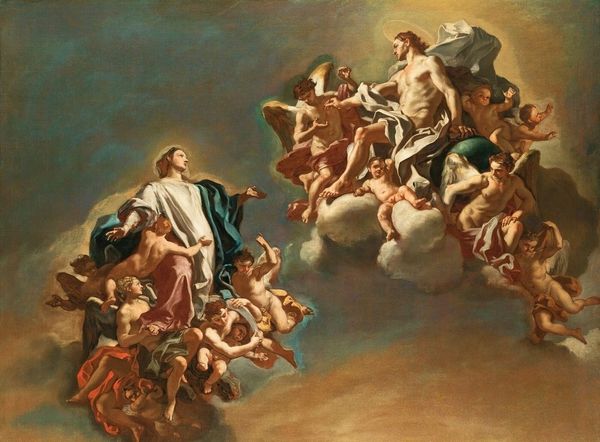

Curator: "Moses Shown the Promised Land" is an 1801 oil painting by Benjamin West, a significant figure in both American and British art history. He's exploring a pivotal scene from the Old Testament. Editor: It strikes me immediately as rather theatrical. The way Moses reclines, almost collapsing against that rock. It reminds me of stagecraft. Curator: Yes, West, influenced by Neoclassicism and emerging Romanticism, often employed a dramatic sensibility. Here, we see Moses at the end of his life, being shown the land he will never enter, a bittersweet moment visualized through idealized figures and divine light. The gender of these angelic figures plays with accepted understandings of divintiy and guidance as typically male. Editor: What interests me is the material handling of light itself. It’s almost tactile, wouldn't you say? The way West builds it up with visible brushstrokes – light is something tangible, almost a woven fabric enveloping the figures. I am particularly interested in his pigment mixing, its opacity. Curator: Exactly, it reflects broader artistic and societal concerns of that period, about divine intervention, leadership, and mortality, viewed through the lens of Enlightenment ideals colliding with a growing interest in the sublime and emotional experience. Editor: And, I would suggest that these are deliberately crafted images created from raw materials such as oil, pigment, and canvas. Thinking about who had access to these types of raw materials gives insight into how this story could even be told through this medium. What choices led West to focus on paint, rather than, for instance, tapestry? Curator: Tapestry as an alternative shifts the discourse to labor. I see the Romantic lens rendering labor invisible; the focus moves to divine vision rather than mortal toil, perhaps because the artist also sought divine status through mastery, leaving labor, and therefore class, unexamined. Editor: Precisely! It's fascinating to see those omissions reflected so strongly. Considering its era and medium, it gives voice to labor that would otherwise go unseen. Thank you for shining light on its story; both material and religious.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.