painting, oil-paint

#

portrait

#

pattern-and-decoration

#

contemporary

#

painting

#

oil-paint

#

figuration

Copyright: Modern Artists: Artvee

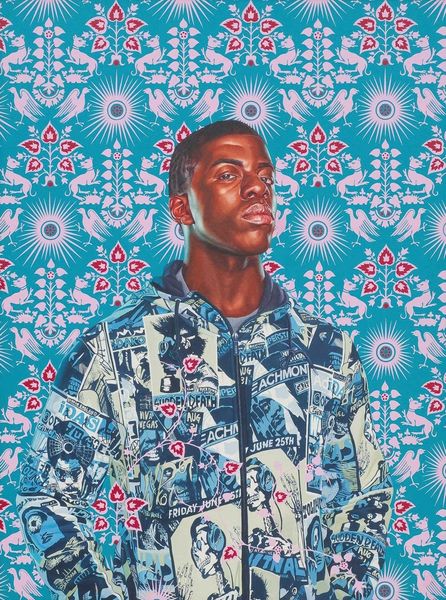

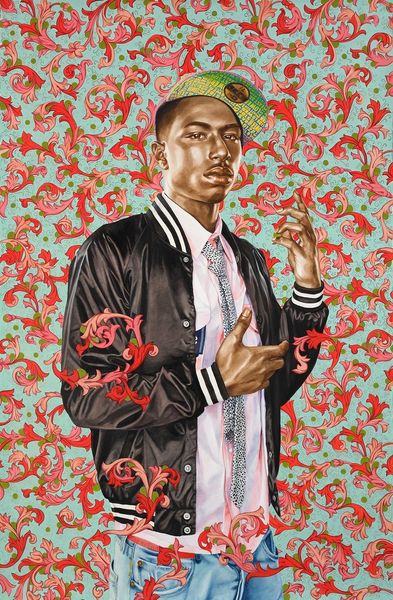

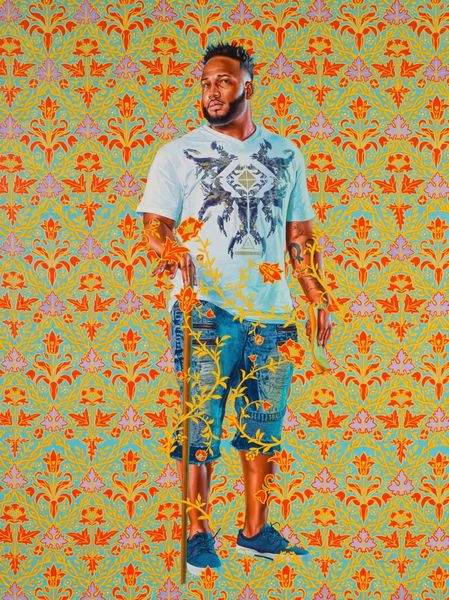

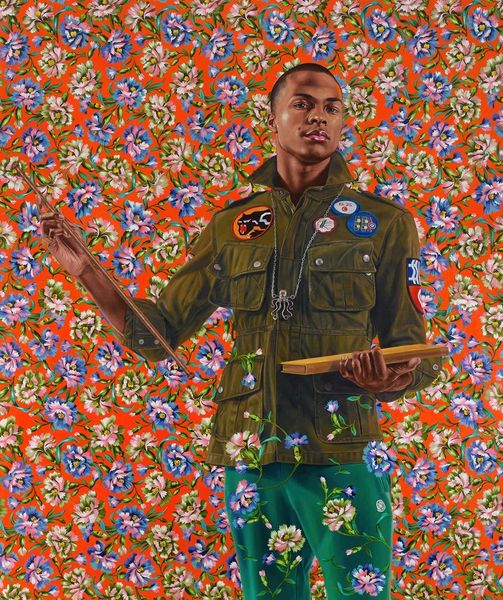

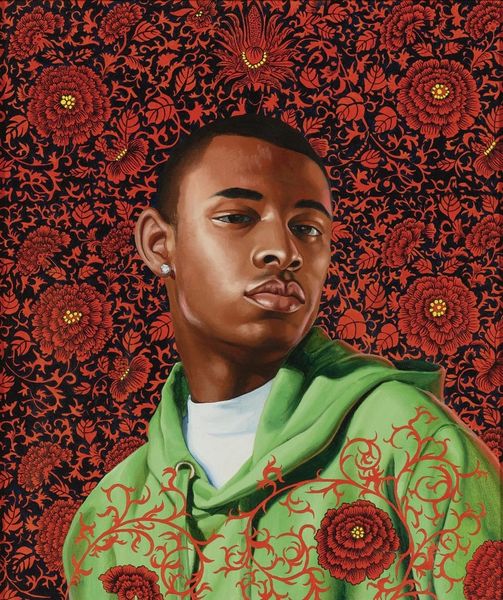

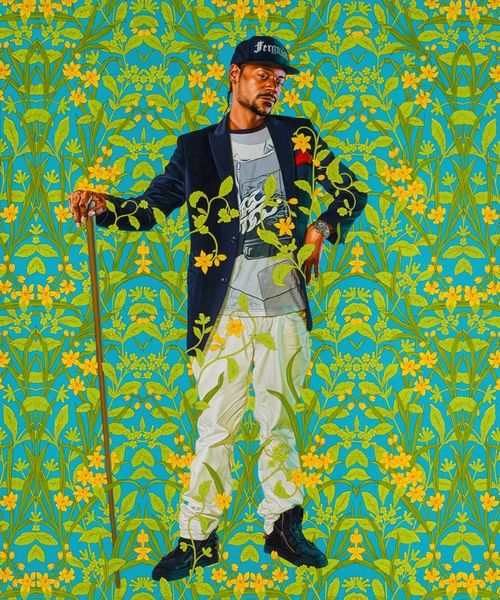

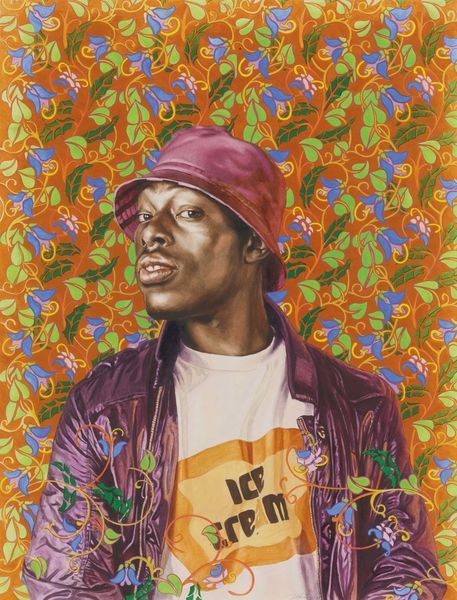

Curator: Alright, let’s dive into Kehinde Wiley’s "Prince Albert, Prince Consort Of Queen Victoria," painted in 2013 using acrylic. My first reaction is wow, those colours explode! It's a figure popping out against this wallpaper-like pattern—like history itself, boldly confronting the present. Editor: Yes, there’s something quite theatrical about the work, isn't there? The appropriation of Albert’s likeness is more than just a stylistic choice, I believe. It raises important questions about representation and power. Why insert this young Black man into that specific historical narrative? Curator: Absolutely. And that's where the magic lies, isn’t it? I read it as Wiley playing with the concept of regal portraiture and queering that stiff, historical, mostly white narrative with something alive, relevant, and brown. It's almost mischievous, really. The pattern he’s set against practically hums with energy too. Editor: I’d say it creates a vibrant tension. The ornate background seems to want to swallow the figure but fails to diminish the sheer contemporary swagger. Look at those yellow pants, those tattoos… he’s utterly himself, yet framed within a context that usually excludes him. The historical gaze inverted. It makes me think of how museums themselves shape narratives by who they choose to display. Curator: Right? The original portraits Wiley's drawing from served to legitimise power through images. Here, Wiley takes those signifiers – the pose, the grand scale usually associated with important historical figures – and offers it to a new generation. He’s handing someone a different sort of scepter to rule with, like self-authorship, perhaps? Editor: Or maybe it's asking what happens when previously marginalized figures take centre stage, demanding to be seen within a framework previously unavailable to them. It makes us reassess what "royal" actually means today. Curator: Mmm, it really does make me think about what histories get remembered, and *who* gets to do the remembering. Like, whose stories get woven into the cultural fabric and whose get tossed aside as being less important or less aesthetically pleasing? Wiley just takes it all and stirs it up, doesn't he? He insists on being loud, beautiful, seen. Editor: Exactly! It’s a conversation about access and legacy, about how institutions participate in either maintaining or dismantling historical power structures. It’s certainly a work that generates conversation, and I would love to hear what others think when confronted with this painting and Wiley’s bold recasting of the past.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.