drawing, pencil

#

drawing

#

light pencil work

#

quirky sketch

#

pencil sketch

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

personal sketchbook

#

sketchwork

#

romanticism

#

pen-ink sketch

#

pencil

#

sketchbook drawing

#

pencil work

#

genre-painting

#

sketchbook art

#

fantasy sketch

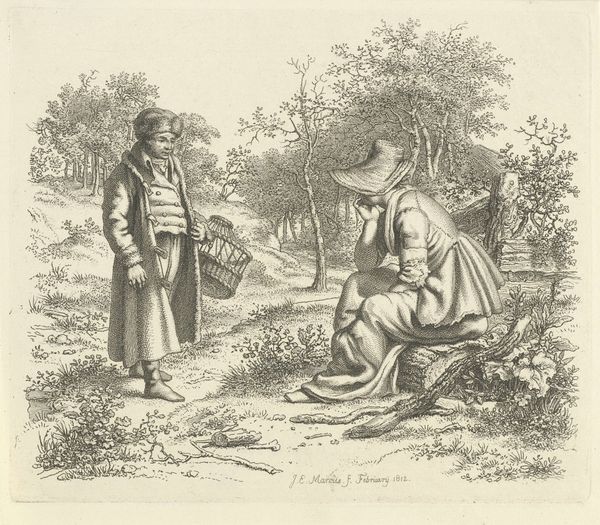

Dimensions: height 180 mm, width 244 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Before us is Jacob Ernst Marcus's 1814 drawing, "Blind Woman and Conversing Figures at a Farm," currently residing at the Rijksmuseum. It’s primarily rendered in pencil. Editor: It strikes me as a rather melancholy piece, despite the figures engaged in conversation. The light pencil work gives it an unfinished quality, almost dreamlike. Curator: I agree; that quality is certainly heightened by the medium itself. It’s a quick sketch, not intended to be a highly finished work of art. Note the economy of line. How that impacts production in comparison to his contemporaries seems important. Editor: It brings to mind questions of social structure – the way blindness may have impacted her interactions and position. The Romantic era grappled with identity quite a bit. I'd like to know more about the blind woman's perspective and how that intersectionality of disability, gender, and social class manifested during this historical context. Curator: Absolutely. There is this element too, that one considers from the labor expended—how the quick nature of a pencil allows more freedom than more labor-intensive production styles of that era. Editor: It’s fascinating how you frame that freedom, though. Is the unfinished, "sketchy" quality actually reflecting some social limitations for the artist? A limitation regarding commissioned artwork perhaps? Curator: Certainly, access can be a critical issue. Editor: It almost feels like a private meditation by the artist, a glimpse into everyday rural life but through a very specific, and possibly constrained, lens. Curator: Considering that perspective, I’m more struck by how those social forces shaped access to certain materials and training in that period. This brings new dimensions of labor, materials, access, and production constraints when considering how we interpret these landscapes from that era. Editor: Right. These details are a constant reminder of whose stories are told, who has access to the narrative, and how those biases inevitably shape the history we consume and reproduce today. Curator: And how materials, practices, and constraints become tied to larger issues and questions of labor practices. Editor: A seemingly simple sketch, yet so rich in contextual layers, reflecting the human condition in both its individual struggles and societal implications.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.