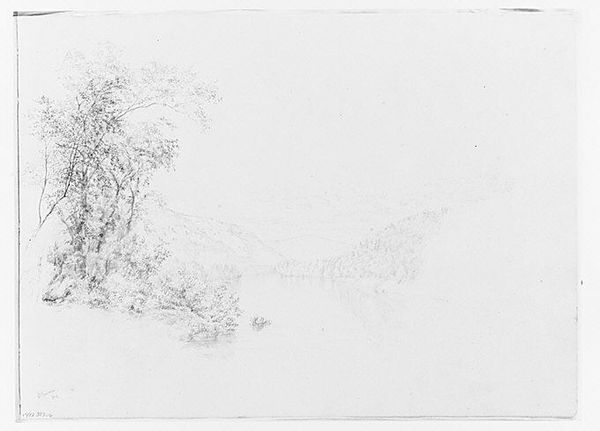

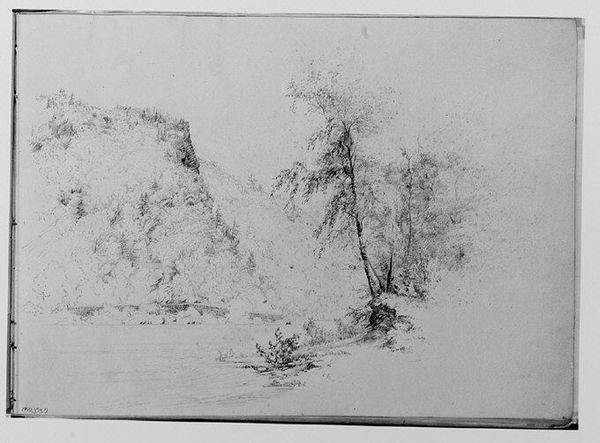

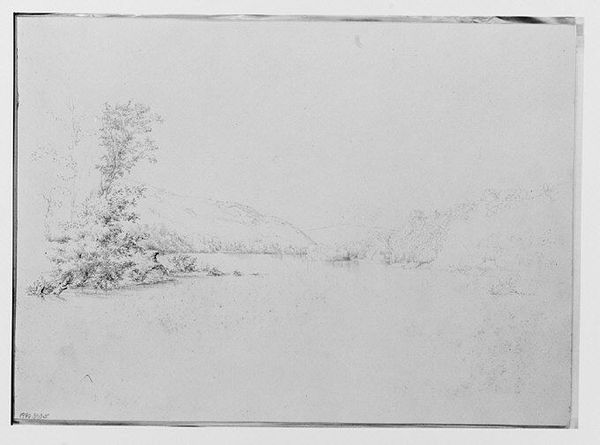

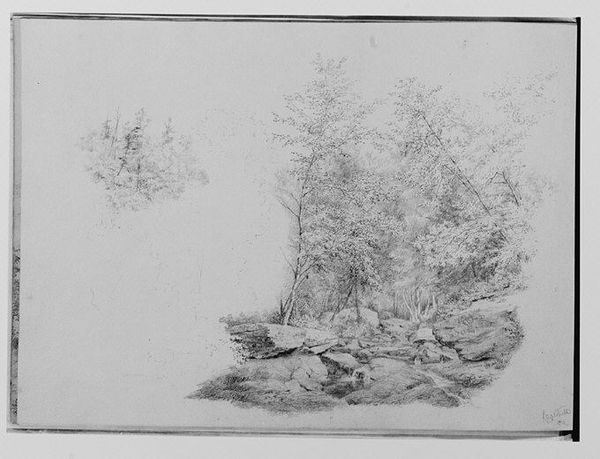

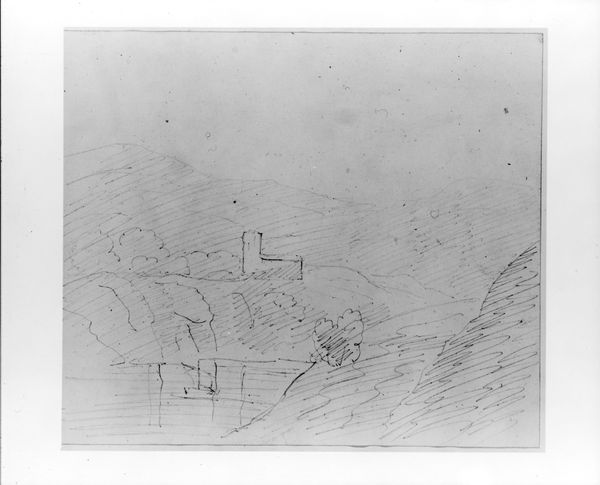

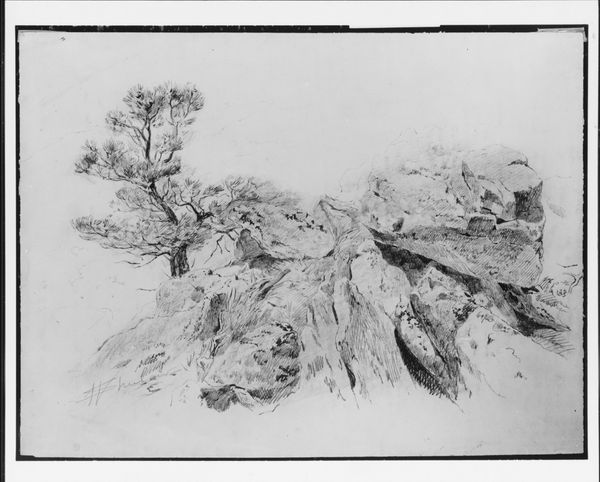

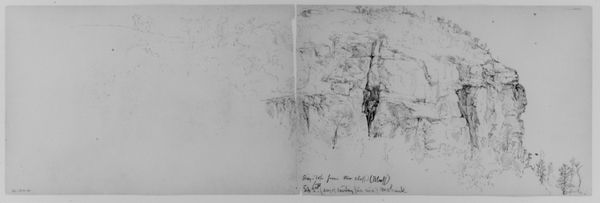

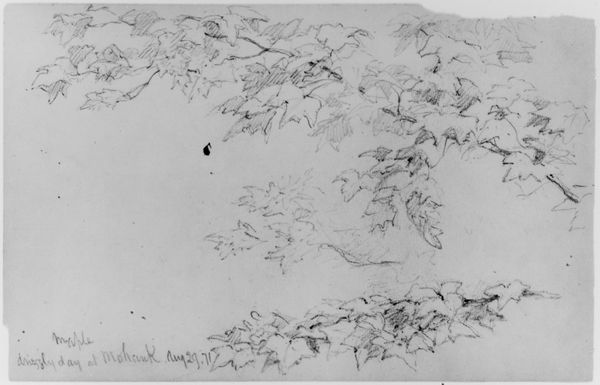

Delaware Water Gap '64 (Mount Tammany) (from Sketchbook) 1864

0:00

0:00

drawing, pencil

#

drawing

#

pencil sketch

#

landscape

#

form

#

mountain

#

pencil

#

hudson-river-school

#

line

#

realism

Dimensions: 9 3/4 x 13 7/8 in. (24.8 x 35.2 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Welcome. We are looking at "Delaware Water Gap '64 (Mount Tammany)", a pencil sketch made by Thomas Hewes Hinckley in 1864. It's currently held in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: Immediately, I am struck by the sheer geological presence conjured through such minimal means. The mountain, Mount Tammany, looms like an ancient, watchful being. Curator: It is fascinating how a simple pencil can create such volume and texture. Hinckley's technique highlights the materiality of the landscape. The lines, almost topographic, define the forms but also demonstrate the physical act of drawing, the hand moving across the paper. Editor: Absolutely. Think about the cultural significance invested in mountains during the 19th century; they represented the sublime, the untamed, even the spiritual connection to nature. Mount Tammany, likely named for the Lenape chief Tamanend, echoes indigenous presences within this vast landscape. Curator: Consider, too, the mass production of pencils at this time. Graphite mining had advanced significantly, enabling artists to produce these on-site studies. The sketch is both artwork and a record of labor. Hinckley likely would have been sketching outdoors, interacting directly with the elements, perhaps even feeling a connection to that indigenous history. Editor: And what of the Hudson River School, of which Hinckley was associated? They often portrayed grandiose scenes to evoke patriotic sentiments, using landscapes as symbols of national identity and pride. What visual strategies are at play here to promote such a cultural narrative? Curator: Hinckley certainly captures a grand vista but his restrained treatment provides only a mere fragment of nature's grandeur; rather than selling a myth of the sublime, it seems much more an empirical study. He focuses our attention on how form itself takes shape under particular light conditions. It’s a subtle dance between artistic representation and nature’s own production. Editor: I see that, even as he suggests underlying psychological symbolism and cultural heritage embedded within the scene. Curator: Well, whatever the intent, observing the interplay between hand, material and subject certainly gives pause to our usual experience. Editor: Indeed. It reminds us that landscapes aren't just passive backdrops; they are imbued with history, labor, and powerful symbols.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.