print, engraving

#

portrait

#

portrait image

# print

#

romanticism

#

history-painting

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: height 223 mm, width 143 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

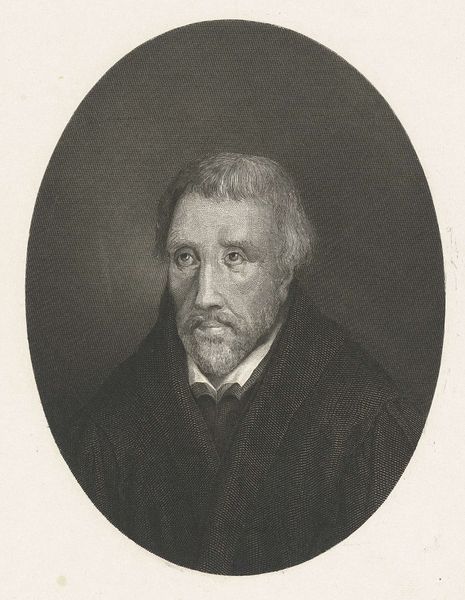

Curator: This is "Mansbuste in ovaal," or "Bust of a Man in Oval," an engraving dating from 1829 to 1845, attributed to Henricus Wilhelmus Couwenberg, currently held at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: There’s an air of melancholy to him, don’t you think? And the starkness of the engraving adds to that feeling of isolation, despite the formal portrait setting. I'm immediately struck by the subtle gradations achieved within the monochrome palette; what strikes you? Curator: I see a complex intersection of class, masculinity, and the politics of representation in post-Napoleonic Netherlands. The oval frame suggests a desire for control and containment, quite literally framing identity within a rigid social structure. We need to also consider this print as a multiple, meant for dissemination and to uphold societal norms. Editor: Precisely! It's crucial to examine the means of production here—the deliberate choice of engraving speaks volumes. Engraving allows for detailed reproduction, and considering the timeframe, it points to a growing accessibility of portraits to a wider audience, beyond the aristocracy. The labor involved in the intricate lines… Curator: ...Reveals a tension between mass production and artistic skill. It's no longer just about a unique, painted portrait for the elite, but about constructing and circulating a particular image of manhood. He's dressed in what appears to be simple, dark attire, a conscious choice to project respectability and civic virtue? Editor: Definitely. The material choices suggest a middle-class aspiration rather than aristocratic extravagance, marking a shift in who gets memorialized and how. We are clearly dealing with a Romantic ideal of "burgher" representation and its manufacturing processes here. Curator: And that brings us back to the individual: How complicit was he, as the subject, in constructing this image, understanding the material conditions and their sociopolitical effects? To what degree does he fit the mould, and to what extent does he challenge it? Editor: These nuances demonstrate how art objects reveal material processes intersecting with questions of cultural capital and class mobility. I find that examination very fruitful here. Curator: As do I! Engaging with artworks this way—linking form and substance—allows us to better grasp not only historical aesthetics but also cultural power.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.