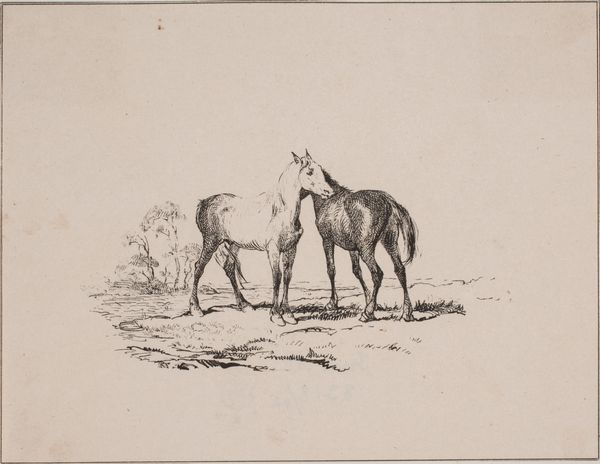

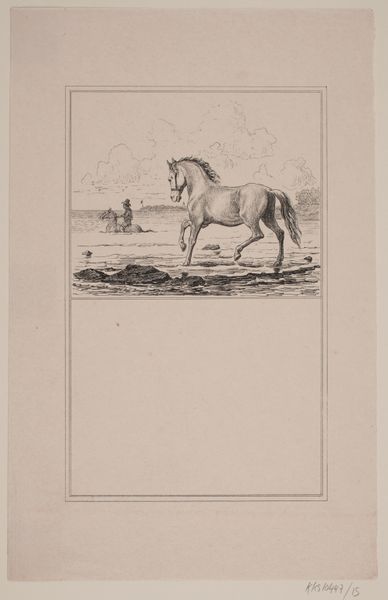

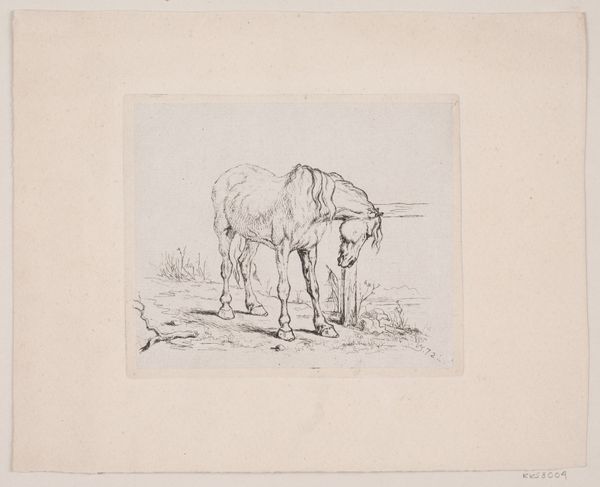

drawing, lithograph, print, graphite

#

drawing

#

lithograph

# print

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

graphite

#

realism

Dimensions: 259 mm (height) x 173 mm (width) (bladmaal)

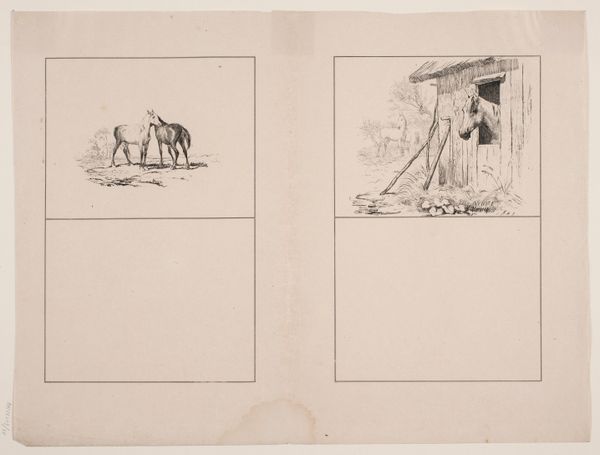

Curator: Looking at Adolph Kittendorff's lithograph, "De to heste," from 1845, I'm immediately struck by the intimacy it portrays despite the simple composition. Editor: It does have a quiet, almost melancholic air. Two horses nuzzling, sketched so delicately—it's sweet but also… subdued. It feels small, even vulnerable in all the negative space. Curator: Lithography, particularly with graphite, was a common means of distributing images widely in the 19th century. Considering the political climate and the emerging bourgeois interest in the pastoral, we might ask: what did images like this signify for the rapidly changing Danish society? Was this meant to evoke ideas around harmony, peace, and national identity through the image of these horses? Editor: I think you’re on to something regarding national identity. Horses often represent freedom and power, certainly masculine power, but in this context, do they perhaps also signal a desire for simpler times, removed from industrialization, as a direct reference and maybe also a silent protest? And aren’t they quite literally yoked? I mean, one is white and one is brown— Curator: That’s a very important observation! The stark contrast, so prevalent in rendering race, becomes striking. By visualizing those together, and in such intimacy, Kittendorff presents a unique commentary about partnership between apparent opposites—not only contrasting gender/race, but more of unity to resist outside pressures. It is rare to find depictions such as this where the animals express gentle affections rather than competition. Editor: It does challenge the conventional narratives—and does so implicitly and quietly—avoiding immediate confrontations with social conventions. This artwork might operate almost as a visual allegory, suggesting new types of interpersonal relationships by taking them away from a place of just domination, a novel suggestion, no? Curator: Absolutely. Exploring the material history and the contemporary reception helps us unearth layers of social messaging often embedded in even the most seemingly innocuous works of art. I never would have expected it on the first glance. Editor: Yes, and considering its subtlety alongside the potent underlying messages it is truly rewarding and deeply affecting.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.