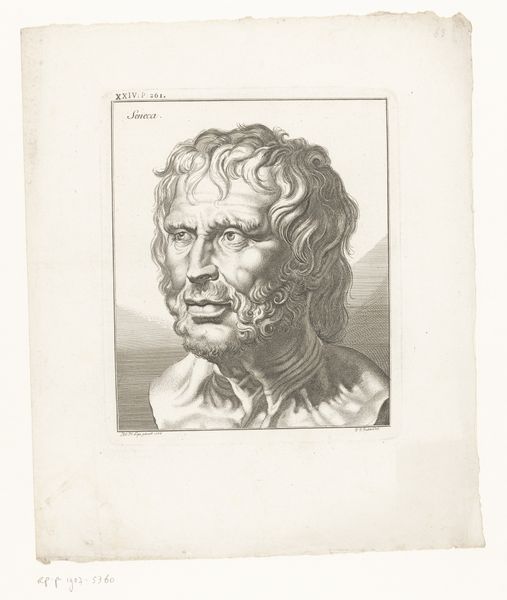

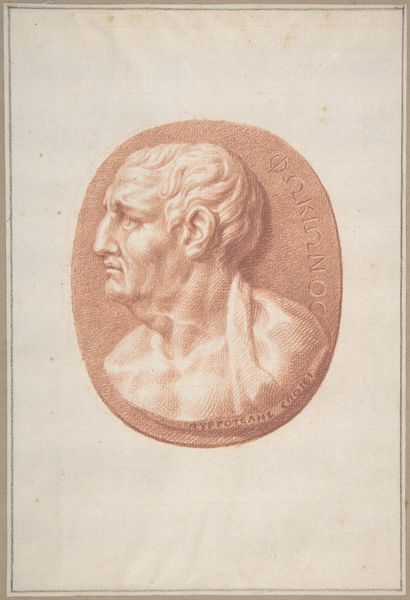

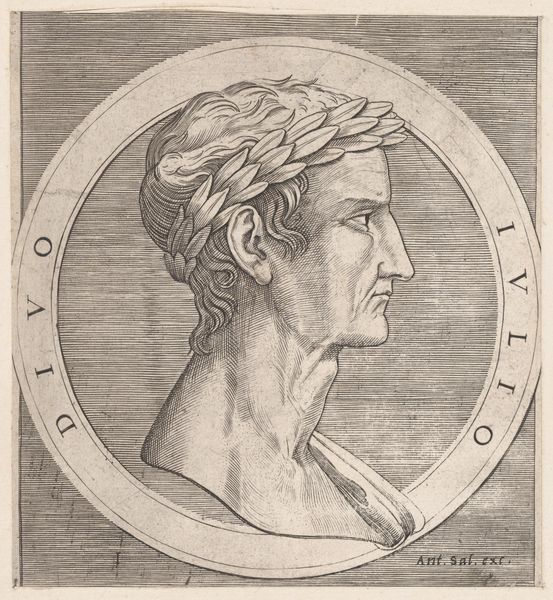

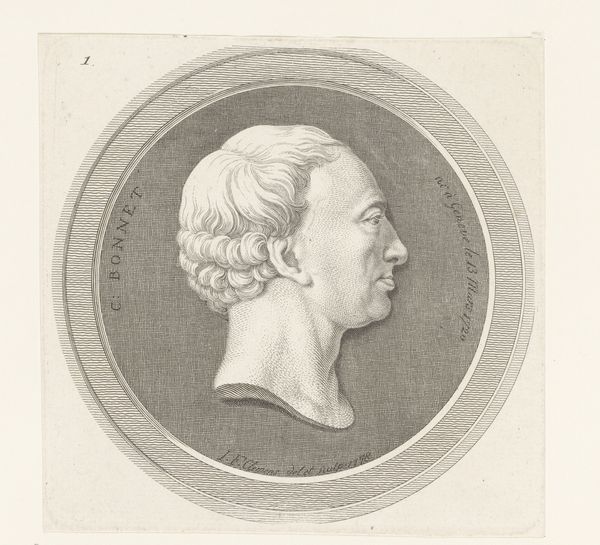

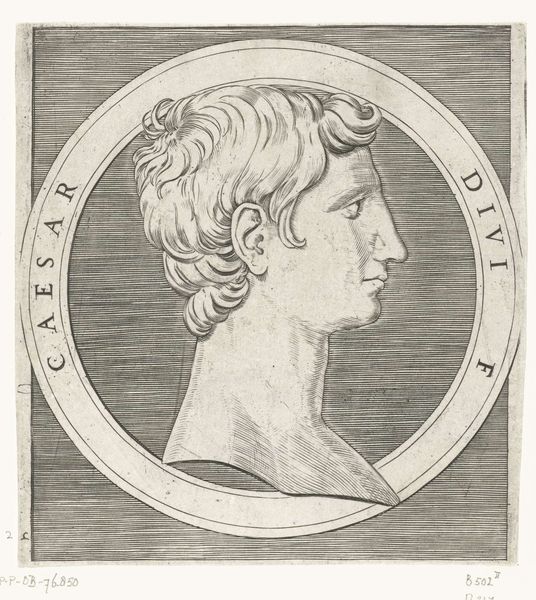

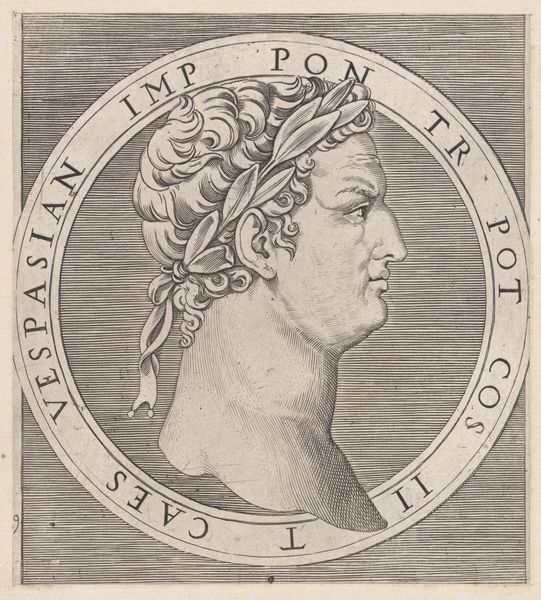

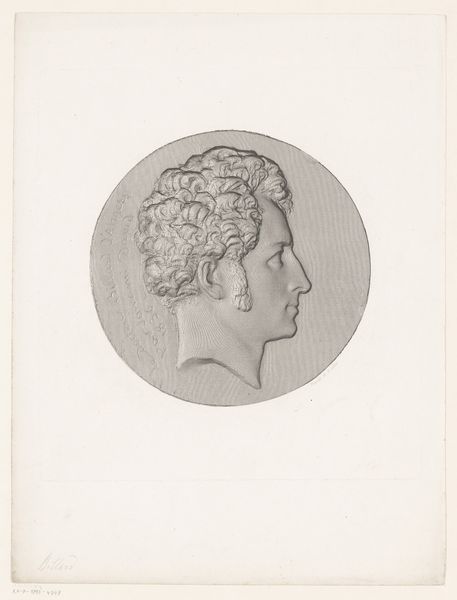

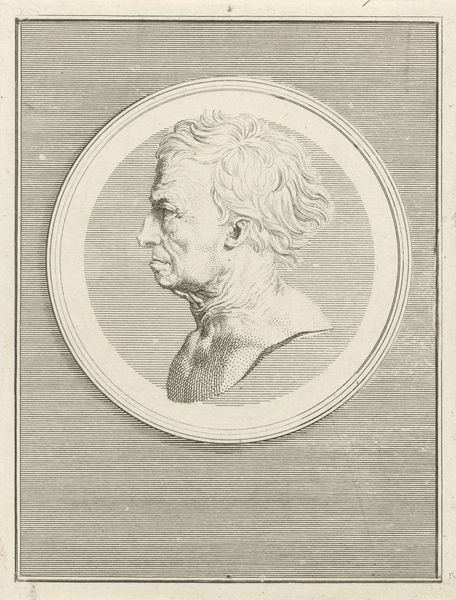

drawing, print, woodcut, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

neoclacissism

# print

#

woodcut

#

engraving

Dimensions: 59 mm (height) x 63 mm (width) (bladmaal)

Editor: Here we have a print of Frederik VI, dating from between 1813 and 1872, by Andreas Flinch. It looks like a woodcut or an engraving, very classical in style. What strikes me is the density of the lines used to create form. How does this materiality affect your reading of the portrait? Curator: For me, the medium is really the message here. Consider the social context: prints like these were reproducible, readily disseminated. This wasn't about unique artistry; it was about creating an accessible image, circulating power. The labor-intensive process of woodcutting, each line meticulously carved, speaks volumes about the intent. Editor: So, you’re saying it's less about aesthetics and more about its function as a reproducible image, commenting on the democratization of power through art? Curator: Precisely! And the choice of woodcut – a more "common" material than, say, etching at the time – further amplifies that accessibility. The very act of carving, the physicality of it, reminds us of the laborers involved in constructing this image of royalty. Were they promoting royalty or just cashing in? Editor: That’s a great point! I hadn't considered the production and how its mass production flattens the concept of a unique artistic object to deliver political messaging. What have we lost by focusing on aesthetics over a more critical review of consumption, class, and material practice? Curator: Well, hopefully this exercise brings us closer to bridging that gap! Material considerations are the real bedrock of our understanding of an art object in a broader cultural context.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.